It wasn’t a surprise to those who knew me as a child that when I start telling stories for a living, they were centered around the forensic and crime investigation world. I started my forensic training almost at birth. My father was a medical examiner for three counties in north Michigan and the coroner’s office was in our home. I was privy to forensic investigation and crime scene procedure from a very, very young age… maybe too young, some might argue. I did my first case at age eight, helping dad discover “left over” pieces of brain and skull from a twin engine airplane crash.

I came to fiction writing later in life, after careers in journalism, PR, and teaching. I was drawn to stories for the screen and thus attended Act One: Writing for Hollywood, an intensive mentor-based writing program. The very first script I tackled was called The Coroner’s Daughter, and became the prototype for the novel series. I was a coroner’s daughter, afterall, and I knew the good, bad, ugly, and smelly about death investigation.

My screenwriting mentors encouraged me to “write what you know.” So, I played the “what if” game. I had never desired to become a forensic investigator myself but… “what if… a young woman who has been estranged from her family, is compelled to return to her small hometown and take over her father’s post as medical examiner?” And with that one question… the Coroner’s Daughter series was birthed.

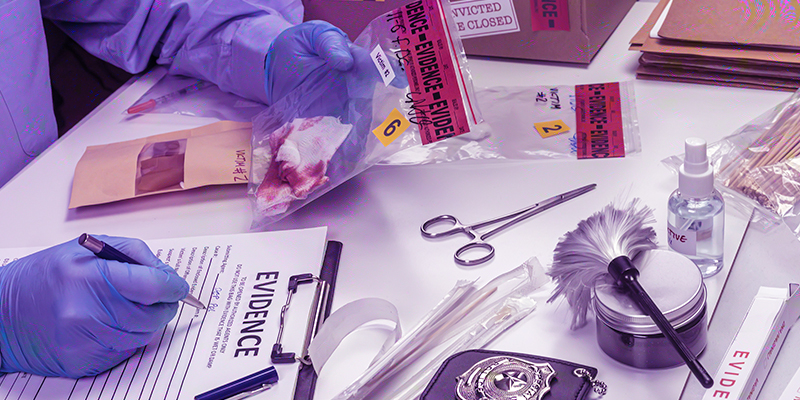

My storytelling is very much inspired by and informed by the training I got at the kitchen table where my dad would recall the latest case. Existing 24-7 in the world of death was like air and water for our family. Dad performed autopsies at the small county hospital morgue, but all the records, paperwork, and photographs were kept in our family office. Samples of blood and body tissue were stored in a basement freezer, right under the pork chops and frozen beans. Dinnertime conversations often revolved around the case of the week. “Let me tell you about an interesting suicide I saw today,” my dad would say. “Oh, and pass the corn, please.”

Dad investigated an average of 100 deaths a year. Accidents, suicides, natural deaths, and scores of drunk driving fatalities filled Dad’s days and nights and kept food in the cupboards and clothes on our backs. During the 23 years Dad worked in forensics, I had a hands-on education in death investigation. It was as natural as brushing my teeth.

One Sunday after church, when I was eight, my father toted us all over to the local airstrip. A small plane had crashed the night before and Dad wanted to return to the scene in daylight to scour the area for any remaining body pieces. My younger sister and I paired up to help him. Outfitted in our Sunday best, we roamed the damp field that early spring morning in search of brain matter and skullcap. And yes, we found some.

I didn’t know a single other person my age whose father kept body bags in his truck and smelled like formaldehyde.Once I reach pre-adolescence, I was painfully aware how different my family was from other families. I felt the need to hide what my father did. We were living in a pre-CSI generation before TV glamorized forensics. I didn’t know a single other person my age whose father kept body bags in his truck and smelled like formaldehyde. Dad’s work was one more reason my peers might reject me. Ironically, my friends found the family business intriguing and to this day, I can’t remember a single time I was teased about what my father did for a living. (At least not in front of my back.)

One of the first times I remember my home life intersecting with my social life was third grade. A new friend came over to play in our fort in the barn loft and soon became intrigued by a 55-gallon barrel. She wanted to take a look inside, despite my strong discouragement. Eventually, she weaseled the truth out of me. I told her, “there’s a man’s leg in that barrel.” It thrilled her. I cowered as she peeled back that plastic and cross section of thigh stared back at both of us.

By my senior year of high school I was a little more comfortable about letting people into the family business. My friends and I hosted a Halloween party for our senior class on our twenty acres. We designed a haunted hunt through the fields and woods with a scary viewing of Sam, our family skeleton, who was a real human skeleton that a doctor friend of my Dad’s bequeathed him. Sam lived in our barn and Dad stuck a cigarette between his teeth. He teased that Sam’s demise was lung cancer—one of his ploys to prevent us from taking on the deadly habit. It worked, by the way.

During my freshman year of college, my best friend who was studying to be a nurse, would often assist my dad with his autopsies. Her time in the morgue was superb training for a nursing career. One weekend I came home from college to find my friend sitting on the front porch with several buckets of decaying human parts soaking in bleach. She was to scrape the bones clean of flesh for a case he was investigating. After the bones were clean, they laid the skeletal remains on the lawn and reconstructed the body to figure out what pieces were missing.

There are a thousand more stories and memories like this from my forensic childhood which led, much later, to a well of fodder for my storytelling. Looking back on all this history, I think growing up around death gave me a healthier outlook on life. We didn’t take the little things for granted. We tried not to hold grudges. We learned that each day could be our last. We tried not to burn bridges and to remember to say, “Thank you” and “I love you” as much as possible.

When I started taking my writing to a professional level, I decided to go back to school to learn how to speak forensics better. My upbringing dealt primarily with death investigation, not so much criminology, DNA, ballistics, and fingerprinting. I wanted to round out my knowledge of crime investigation so I attended the Forensic Science Academy in Los Angeles. When I was telling my writer friends about my experiences in the academy, they said that they wished they could go through it. I thought, well, why not put the academy in book form for those who aren’t able to take the academy? That inspired me to create a book built on the forensic foundation we were taught in the academy. That book is called Forensic Speak and it’s basically a forensic bootcamp in a book. And it’s been used by writers, showrunners, and even law enforcement.

Along this journey, I’ve also been able to use my forensics background to help others in film and TV speak forensics better, consulting with writers who worked on shows like Bull, Conviction, Hawaii Five-O, Leverage, Suits, and Rectify. I’ve also tackled numerous questions for authors and novelists. They challenge me with really interesting questions like… If a body was burned to ash, how much tissue/bone/teeth/other substance do we need to DNA match the remains?

You don’t have to grow up with bodies in your home to learn how to speak forensics. Forensic Speak can help; so can a little research or asking a professional in the field.

***