How do you feel about murder? Me? I’m against it. Let me say that right from the start. I think murder is wrong. And if we’re agreed that murder is wrong (I’d like to think we are, though there may be a few dissenters) then why do so many of us find it comforting?

There is, you’ll have noticed, a literal genre titled “cozy crime.” Isn’t that the very definition of an oxymoron? It makes no sense.

And yet we are in the midst of a cozy crime boom. Hoards of us banging at the doors of our local bookshops, trampling over the romantasy fans and demanding copies of The Very Lovely Murder and Mrs. Bobbins’ Delicious Murder Shop. Those novels don’t exist but you have to admit, you would not be at all surprised to see them on a shelf. What is driving this boom?

There’s a theory that the world, as it is now, is so awful, so terrifying, that we are seeking solace in gentle things. It’s not a bad theory. I would argue that a variation on the phrase “what is the world coming to?” could be, and indeed was, said in any and every era. Perhaps the particular trouble with the one we’re currently experiencing is that as soon as something terrible happens, anywhere on earth, we immediately know about it.

Anyway, I’m not here to tell you not to believe your own eyes. If you’re finding the news frightening, that’s a rationale response. Running yourself a literary bath and picking up something cozy, seems a good choice to me. Is it pure coincidence that the Golden Age of crime fiction coincided with the 1930s?

The cozy part makes absolute sense. But why crime? If I’m stepping into a bath to relax, I do not want a murder thrown in.

Here’s the thing—and I’m sure you know this, I’m just articulating it for you—the murder in cozy crime isn’t real. If it was, then my parents wouldn’t have been so comfortable with me watching so much of it.

Sunday nights in the U.K. were traditionally the place for Agatha Christie adaptations. I’d sit there, as a ten-year-old, in my pyaamas, with my milk and cookies, watching Poirot or Mrs. Marple solve murders. Then there was Inspector Morse, based on the Clive Dexter novels, a detective interested in classic cars, crosswords and opera.

And of course there was the greatest of them all: Columbo, a man who was on the LAPD for at least thirty years and never once, to the best of my knowledge, encountered gang crime. When Rodney King was beaten, Columbo was no doubt interrogating an eccentric theatre director about a murder committed with a prop gun. When the LA riots were in full flow, veteran LAPD cop Columbo would have most likely been quizzing a zoo keeper about one of his staff being mauled by a bear.

These are, I should say, not real episodes. I’ve made them up to make a point, but I’d like to think that had I been born thirty years earlier, I could have done good work in the Columbo writers’ room.

People do not open a cozy mystery to get an in depth exploration of actual murder. They read them for the comforting puzzle that a murder mystery presents. A collection of entertaining characters will gather. A “murder” will take place. The entertaining characters become our suspects. Unless it’s our first murder mystery, we already knew they’d be our suspects and have already started examining their behaviors.

Then we have our sleuth, typically amateur, or at least charmingly out of the ordinary. They will carry out an entertaining investigation, during which we get to peer into a section of society. Perhaps a church bell-ringing club or a book group riddled with petty rivalries.

Along the way, there may be room for satire. There may even be space for a our hero detective to meet danger. But we know, we know, from page one to page done, that our sleuth will solve the crime, our murderer will meet their demise and all will be explained.

Murder in the real world is vicious and confusing and there are no happy endings. And now I will tell you something that does not fall into the category of cozy: in 1972, before I was born, my grandfather was beaten up outside a pub in Cornwall, England. Six months later, he died from the injuries.

One of the assailants was never caught; the other was, before my grandfather had died, given a fine for assault. He could not be tried again for the same crime so that was that. My grandmother would still see the men who killed her husband regularly in the town they lived in. My mother saw him less than ten years ago. He saw her. He knew who she was. She knew he was.

That is murder in the real world.

It is little wonder that so many of us want to escape it with a more palatable alternative.

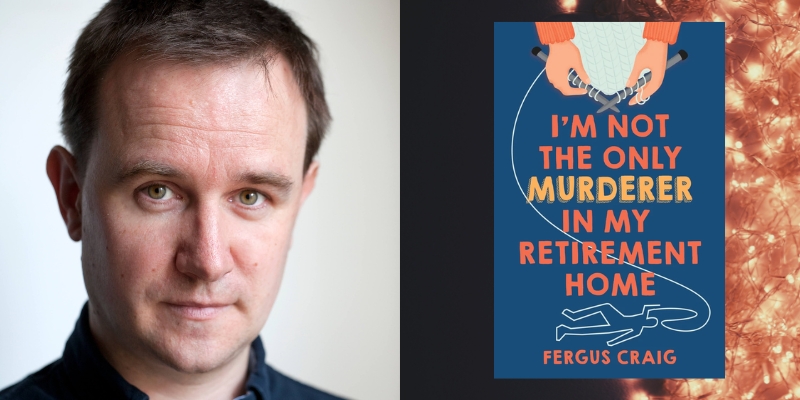

In my next book, I’m Not the Only Murderer in My Retirement Home, I wanted to play with the genre, to push it a little, test its boundaries. It’s not a parody of cozy mysteries but a riff on them, so to speak. I wanted to see if I could take a quintessential cozy setting—a grand, luxury retirement home in Hampstead, an affluent area of London—and throw in a serial killer.

The hook is simple: Carol Quinn, a seventy-five-old retired serial killer leaves prison and arrives at Sheldon Oaks, our pleasant retirement home. Then someone is murdered and, of course, everyone assumes Carol did the murdering. Now she has to find the real killer, to clear her name. What makes that task more difficult is that every other resident at Sheldon Oaks seems to be a retired investigator of some sort.

Knowing that I’d be writing about a serial killer, I started my preparation by reading about real serial killers and watching real serial killer documentaries. Quickly, I came to a conclusion: serial killers are not very likable people. Actually, and I do not say this lightly, they’re horrible!

I wanted Carol to be likable. I wanted her to be witty, sometimes sensitive, aware of her flaws. I wanted the reader to perhaps even sympathize with her. So I created the only serial killer I would like to meet—a fictional one.

I also wanted the book to be funny. That’s my wheelhouse and I’m very happy staying there. Once you remove the possibility that this is about a real killer, about real murder, the opportunities for laughs are plentiful.

A breakthrough moment for me was considering Carol’s thoughts whilst baking with her new friends: “Carol looked around her, as she often did now, and thought of all the killing implements that were suddenly available to her. Decades of not being trusted with metal cutlery and now, right in front of her, was a knife rack.”

Along the way, I discovered that, although I was writing a cozy mystery, that did not mean there wasn’t room for truth. Carol and the friends she makes are real people. They may be heightened, comic characters, pieces of a puzzle I’m playing with the reader, but they can still have genuine feelings, fears and regrets that I hope people can empathize with.

So, as I began, I thought I might be writing a spoof. Instead, I wrote a celebration of and an ode to the cozy crime caper.

Cozy mysteries are fairytales for adults. I do not say that to deride them. I think they’re a good thing. We deserve fairytales. We deserve happy endings.

***