Movies are loud. They are often written and written about in clamorous verbiage: they leer and loom, assault, pummel, and thunder. They are religion and sex strapped together into a rig of worshipful attention, all spectacle satiation and ritual subjugation. Before every contest, the screen starts at black. Our heart races. The device ignites. Let’s ride.

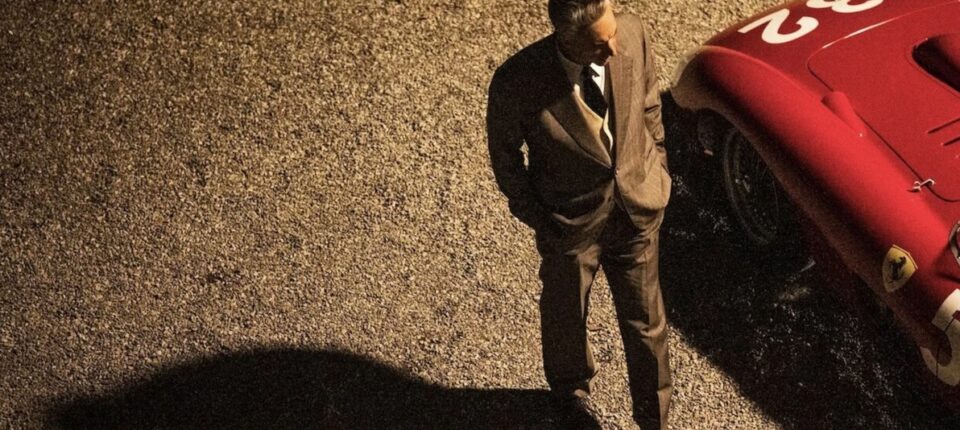

Enzo Ferrari watches from the side, on the screen, over the radio. Enzo Ferrari is big. He’s almost as big as Adam Driver. His frame can take the pressure and the combustion. This is good. It will receive it, in near constant and constantly-increasing doses over the 130 minutes that make up Michael Mann’s Ferrari, an opera pitched to holey muffler decibel. This is not just a metaphor. Ferrari goes to the opera in Ferrari. He knows what he needs to feel. He seeks the outsize wallop of beauty amid the crash of daily life. Overture, recitative, aria, high note. Coda. Somewhere in the singing, meaning and meaningless run neck and neck. Then applause, the way our hands stop gripping the seat. It’s loud, but by doing it, we learn to die, over and over again.

Ferrari is the daily life. Delayed by production trouble—which is to say, creation trouble—but promised by Mann since 2000 AD, it is neither the story of a Great Man nor a Fall From Grace. It’s just the track of land that makes up the race and the way a body moves across it. Enzo wakes up in the casual crisis any body experiences under any capitalism: he is running out of money. He has bargained on his art being his business and business is demanding more tribute, more time, a watering down of the fuel to make it last. Driver plays Enzo like a line of merlot dribbled into eggshell paint; inside the fine suit of Mastroianni, there’s a Gandolfini breathing. He lumbers from the bed of his lover, Lina to the room of his wife, Laura. The daily life begins all over again.

The syllabic similarity of these names teases; the women of Ferrari move and speak as if captured by different cinematographies. Lina, played by Shailene Woodley, moves over earth easy, listens gently but firmly. She and Enzo have a son and a house and life hidden from the world, from the daily life. Is it magic? Cinema can create a life and then sequester it in editing, as this narrative thread is sequestered from Laura, from Ferrari’s wife. Penélope Cruz is one of the great actors of this or any day. Her insight for seeing the melodrama inside of tragedy and her instinct for drawing these notions out like a painter is largely unmatched in the ecology of moving image. She feels a feeling and performs it. Laura is wounded and vengeful: she had a son with Enzo. Their son died, and their marriage began bearing the slow crash of quotidian grief.

Driver plays Enzo like a line of merlot dribbled into eggshell paint; inside the fine suit of Mastroianni, there’s a Gandolfini breathing.Two lovers, alive but separate. Two sons, one alive and one dead, both animated in memory, which is one of the many dialects cinema speaks. Enzo is the fulcrum between these worlds. There is also the death of his brother, at the hands of racing, which is Enzo’s art and business. And there is the death of Enzo, or rather, the memory of a way he was once. We glimpse him in mock newsreel footage: Enzo the racer facing death like Paul Muni, like John Garfield. There is glamor in keeping pace with death. Or maybe it’s fashion: in flashback we see Enzo half-dressed and in love with Laura, his hair less-grayed by living, his body open to her and us instead of shuttered in the business of a suit. Laura wants, a lot and often in Ferrari. She wants this, but also a life where this isn’t her only economic option, her only avenue towards agency.

“Strong female character” can still waylay criticism. And rather than righteous frustration, its utterance moves closer to brandable tradition—even as Marvel flails, The Marvels (2023) insists that any body can be an IP zombie. It can inadvertently (or worse, intentionally) designate representational politics an end goal to the sensual, speculative process of art. It misses its own point, which is: by writing strong characters and casting strong actors to play them, a cultural object’s inner tension can increase. Its complex grows by its contradictions, by the opposing gravity of its strong forces. If Laura and Lina are strong characters, it’s because Ferrari and its actors write their desires as worth inhabiting, carnally, philosophically, materially. That the performances make strong choices means the film produces its own stakes rather than hoping to be a metaphoric figuration for something else. Wanting is worth watching. What else is there?

Things happen in Ferrari, too. Enzo wakes up, greets his ghosts; the film begins and ends in cemetery reverie, which is not a spoiler unless you consider life spoilable. His business is running out of capital and time. His wife is disgusted by him, and she doesn’t even know about his secret other life yet. But she does wield power over half of the company, which means Ferrari can’t be sold or moved without her acquiescence. The lingua franca of this midlife crisis is brand: Fiat will absorb the company, but compromise it. Mazerati licks its fender chops, advancing. What must Enzo do? He must win the Mille Miglia, an open-road endurance race. A win will restore glamor, life, and profit. In 1957, the year of Ferrari, Enzo drives in the immaterial sphere of cost analysis and liquidation. His team drives the race cars.

In constructing a community of men inside a world made for and by them, Mann establishes the themes of his opera is bold lettering. It’s a little like Sofia Coppola making a film about Priscilla Presley, in that you could call the move obvious—don’t you want the obvious to be a mode approached by grand artists? Opera is obvious, as is desire and disgust. That these films (which played together at the New York Film Festival) and their feelings hit on themes familiar to their filmmakers is a reminder that repetition is the mode by which the novel emerges. Another lap, another hour waiting around Graceland. If there are men and girls—just two of the myriad ways to be—in the world, they deserve to be sketched like engines and then made to run. When we watch, we get to see the changes, and maybe get to be changed.

Nobody races alone. The men of Ferrari follow Enzo with the gravity of narrative; there is simply no alternative. There is a new racer. Alfonso de Portago (Gabriel Leone) is fresh-faced and handsome, looking out at the merlot steel of Erik Messerschmidt’s cinematography with the thought of glory, of being the hero. In another movie he might be the protagonist, but here he’s just another head chumming up above the hydra to drive the name around. More knowing and impressionable is Peter Collins (Jack O’Connell), who moves like a chic Karloff. Death is sex in Ferrari, as haunted as the empty bed or a preemptive crash note addressed to the beloved. Newly-crowned Sexiest Man (citation needed) Patrick Dempsey is very nearly actually sexy as Pierro Taruffi, the old man of Ferrari’s racing team. If he is sexy, it’s because he forsakes the stubble charm Dempsey has leaned on his whole career for something hungrier and more desperate: the myopia of desire. To race is to want to finish, to see the long haul of road required and to force your body to move along it. You have to win the Mille Miglia, even if the body doesn’t finish it.

The men of Ferrari’s racing team are not strong. They do not actuate or activate. They move under the influence of narrative gravity. An opera contains many roles, and while its leading players choose how they engage with the score and space, a chorus is bound by how they echo. The man of Ferrari has a cadre of empty devotees while the women have the emptiness of a name being traded like stock speculation. One reading of the film might suppose Lina’s behavior as typically feminine while projecting a degree of masculinity onto Laura, onto her stooped stepping and willingness to fire off. There is a corona of homoeroticism, certainly, in the way men will die for Enzo, in the way men do die, desperately, for Ferrari. The song of the film—“go beat the hell out of them”—doesn’t dwell on these traps of self-ideation: it drives them.

No body races alone. Enzo’s personal life crashes around him partly because he insists on shoving himself through the film, an object at the expense of others. Will he acknowledge his secret life and gift his secret son the name ‘Ferrari’, like the departed one before him? People replace people in Ferrari: “Two objects cannot occupy the same space at the same moment in time.” But a name is a brand and identity is doubly precious jockeying for position against a memory. Will Lina be freed of the patronization of the pastoral? And does that liberation come at the expense of Laura’s desperate careening, if not for love than at least for meaning? Guns go off, as do trysts, apprehensions, and clothes. In Collateral (2004), Mann used digital to bridge the neon-gaseous bodies hanging in Los Angeles air, the literal fault in our stars. Public Enemies (2009) pulled that starkness through portals of Americana—outlaw justice, lawman fascism, movie palace false-majesty—to suggest a cinema of opposites whereby in America, the people are on the losing end of fantasy. Dillinger must die, we know that from the outset. Ferrari moves beyond the American problem to one of its sources, in the rebuilding of post-war Europe. Things replace things in Ferrari and the cost is never far from the camera’s eye. The digital here, both neon and grave, rebuilds the notion that film stock alone is sensual. It’s a welcome engagement with the body in a story that could have been about an automobile. It reminds me of mine, all the time.

Movies are loud. This is not a metaphor. Sometimes they are too loud for me, as in the screening of Michael Mann’s Ferrari I attended. In a 2013 interview, Lily and Lana Wachowski talk about “how every audience member has a relationship to a camera being related to time and space,” about “you have to move a camera through space and it takes a certain amount of time.” To become aware of your body during the unspooling of film is to realize that time is passing, that you are spectating its swift dictum. “We talked about,” the Wachowski sisters go on, “could you put a camera on a rocket?”

All of Ferrari’s mea culpas, familiar to and novel in Mann’s cinema of (on the clock) time are expressed in the film’s real innovation: a camera on a carburetor. During its driving sequences, the camera sits as if the car sees, punching into the future. Watching this cinematography on a large screen is thrilling and debilitating, wearing just as being a body in the world is. The camera’s placement means that the rev of the engine plays loud, fierce, uncompromising. Two objects cannot occupy the same space at the same moment in time. The camera must sit atop the engine, cinematography rendered as riding the chainsaw.

We strap ourselves to so many volatilities. Some, like cinema, promise transformation even if they don’t always make good on the deal. I think when we talk about the transformative power of art—itself a treacherous if romantic slip—we’re really saying “desire.” To submit to its fabular power, as Ferrari does, is to absorb the rules of representing history and memory and introduce the strong tension of artifactual embodiment: we’re us and the automobile, our selves and the cameras, the song and the singer. Beyond the lesson of the image (the trap of masculinity, say, or the bone grind of capitalism or the ascension of grief) are its myriad parts. Looking at many things at the same time, a race isn’t a metaphor but a feeling, in your ear drum, in your belly, in the space between living.