January 12, 1925

The most powerful man in Indiana stood next to the new governor at the Inaugural Ball, there to be thanked, applauded, and blessed for using the nation’s oldest domestic terror group to gain control of a uniquely American state. David C. Stephenson was sandy blond and thin-haired, with blue-gray eyes and a fleshy second chin much too middle-aged for a man of thirty-three. Charm oozed from him like grease from a sizzling sausage. Everyone called him Steve. But in print, in posters, in letters and telegrams and flyers all over the Midwest, he was known as the Old Man. He preferred that name, and the mystique that went with it, to the only formal title he ever held: Grand Dragon of the largest realm of the Ku Klux Klan the world had ever seen. He was driven to work in a Cadillac, a bodyguard next to him, and never left his pillared white mansion without a revolver strapped to his chest. He looked well fed, well dressed, certainly well satisfied at the reach of an Invisible Empire that was secretive no more.

In his suite of offices inside the Kresge Building, located at the crossroads of influence and history in downtown Indianapolis, he kept seven black telephones and a single white one. The standout was a direct line to the White House, he told guests. Numerous visitors overheard him say, “Thank you, Mr. President, and give my best to Mrs. Coolidge,” as they waited for their ration of the Old Man’s time. On his desk was a bust of Napoleon. The Emperor was a role model, but even he might blush at the claim that Stephenson made to his inner circle: “I am the law.”

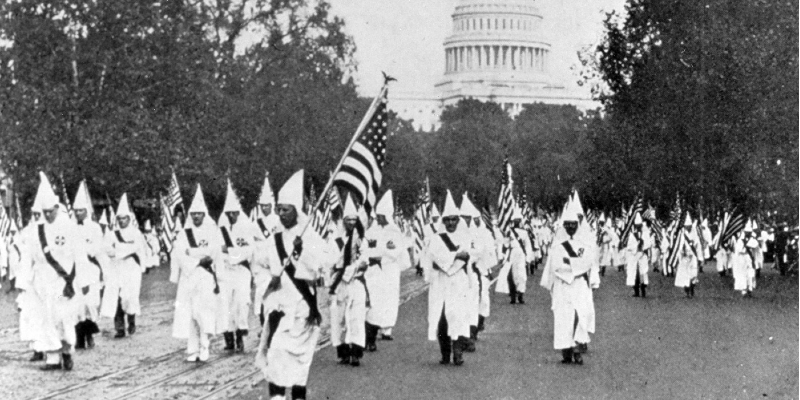

You could doubt that, for he had been elected to no office, appointed to no board, hired by no police department or district attorney, named to no court or panel of judges. The only oath he had taken was the one sworn by up to six million men nationwide who donned full-length robes and covered their faces in sixteen-inch conical hoods, formally vowing “to maintain forever white supremacy.” Yet a look around the ballroom of the Indianapolis Athletic Club, where 150 of the most influential citizens had gathered to fete the new governor, would leave little uncertainty about who controlled the state.

On this winter day, Stephenson was triumphant, “monarch of all he surveyed,” as the New York Times described him. It had been barely four years since the reborn Klan moved across the Ohio River and spread north. But now crosses burned all over the state. They burned on the lawns of Black families. They burned near Catholic churches and Jewish synagogues. They burned across the street from police stations. They burned near cornfields at the edge of small towns. They burned after Sunday services and Independence Day parades and Christmas week sleigh rides. Torching an oversized cross was theater of intimidation, leaping flames on the night horizon, but also a thrilling bond of brotherhood. Hoosiers were joiners. And in 1925, if you were not a knight of the KKK, you did not belong.

The Klan owned the state, and Stephenson owned the Klan. Cops, judges, prosecutors, ministers, mayors, newspaper editors—they all answered to the Grand Dragon. He was backed by his own private police force, some 30,000 men legally deputized to harass violators of Klan-certified virtue. Most members of the incoming state legislature took orders from the hooded order, as did the majority of the congressional delegation. From the low-bank shores of Lake Michigan in the north to the fat bends of the Ohio River in the south, from the rural folds of a county where Abraham Lincoln grew up in a small house that nurtured big ideas, to the windowless shack along the tracks where Louis Armstrong cut his first jazz record, the Klan infested Indiana. All but two of the ninety-two counties had a chapter—the only state with such saturation. One in three native-born white males wore the sheets. And here was yet another plum: Ed Jackson, the Republican whose name had first appeared on membership rolls of the Klan in 1923, had been swept into the governor’s office. He owed it all to D. C. Stephenson.

In the golden age of fraternal organizations, the Klan was the largest and most powerful of the secret societies among American men—bigger by far than the Odd Fellows, the Elks, or the Freemasons, and vastly greater in number than the original Klan born in violence just after the Civil War. Gains over the last few years, mostly in the North, had been astonishing. A Klan mayor ruled Anaheim, California; the city was nicknamed “Klanaheim.” A KKK chapter was chartered on board the USS Tennessee, a battleship anchored off Bremerton, Washington. “The Invisible Empire now has a floating Klan,” crowed the order’s national paper, the Imperial Night-Hawk, which had a larger circulation than the New York Times.

In Colorado, an open Klansman, Clarence Morley, won the governorship on the same day that Ed Jackson did in Indiana. He promised to fire all Jewish and Catholic professors at the state’s flagship public university. “Every Man under the Capitol Dome a Klansman” was his motto. He joined another Klan-backed governor in the West, Walter M. Pierce in Oregon, who endorsed a voter-approved measure that would essentially eliminate Catholic schools. “Keeping America a Land for Americans” was his slogan. The Klan claimed fifteen United States senators under its control, and seventy-five members of the House of Representatives. Many had sworn allegiance in secret Klan initiation rituals, becoming “naturalized,” as it was called.

But the epicenter was Indiana, which was trying to shape human behavior as no state had ever done. At mass rallies, Stephenson and other Klan leaders cited the latest research from influential eugenicists, detailing the skull size, personality deficiencies, and other indicators of inferiority by those not of strict Nordic stock.

The state had passed the world’s first eugenic sterilization law, targeting “idiots, imbeciles, and confirmed criminals,” as the statute dictated. The Klan was now pushing for a more severe measure, singling out paupers, alcoholics, thieves, prostitutes, and those with epilepsy to be sterilized against their will.

Stephenson’s vigilantes assisted the police in enforcing the harshest anti-alcohol laws outside the Muslim world. Prohibition, which Winston Churchill called “an affront to the whole history of mankind,” had become the law of the land in 1920. It had long been pressed by the Klan, aimed at Irish, Italian, and German Catholics as part of a crusade against the meeting places and social rituals of immigrants, and at Black men whose lust for white women was said to rise with the ingestion of liquor. Indiana went much further. The state made it illegal to display flasks and cocktail shakers in shop windows, or to sell hair tonic that contained a whiff of alcohol. A new law criminalized possession of an empty bottle if it still had the smell of liquor. Punishment was thirty days in jail.

The America of the 1920s was roaring in some quarters but repressive in many others. The first twenty-five years of the new century were the “swiftest moving and most restless time the world has known,” wrote Booth Tarkington, Indiana’s most celebrated author. In the South, whites had wiped out Black voting rights. They put in place Jim Crow laws that prevented more than one out of every three citizens from owning property in middle-class neighborhoods and from eating, sleeping, traveling, shopping, or going to school with whites. That system was locked down, backed by a Supreme Court ruling with only one justice dissenting. Now the Klan was moving swiftly in its new strongholds in the North to extend suppression of Black families in everyday life.

The twentieth-century Klan was also fighting to close the door on those whose religion, accents, and appearances made them suspect in large parts of the United States—mainly Eastern European Jews, Polish and Italian Catholics, Greeks, and Asians.

“No one can deny that the United States is a white Protestant country,” wrote the Fiery Cross, the weekly newspaper of the Indiana Klan. Stephenson’s press organ was filled with scare stories of those seeking to find a home in a new land. “We receive at our ports of immigration an ignorant and disreputable omnium-gatherum of scorbutic and vicious spawn, people who possess neither blood nor brain, unclean and uncomprehending foes of American ideals.” The governor of Georgia, Clifford Walker, told a Klan rally in 1924 that the United States should “build a wall of steel, a wall as high as heaven” against immigrants.

And in these first days of 1925, the ultimate political design was within reach: a Klan from sea to sea, north to south, anchored in the White House. It was an absurd idea only to those who believed that a vibrant young democracy could never be given over to a gifted charlatan. The Klan had been so influential at the 1924 national conventions of both Democrats and Republicans that Time magazine had put Imperial Wizard Hiram Wesley Evans on the cover, and dubbed the GOP gathering the “Kleveland Konvention.” The Klan got most of what it wanted at both national party meetings. When Evans went to Colorado later that year, he told a gathering of thousands of new initiates who filled a stadium that they had just joined “the most wonderful movement the world has ever seen.”

As Stephenson welcomed the fresh crop of politicians under the Klan’s thumb today, it was an open secret that Indiana Senator Samuel Ralston did not have long to live. Should he die, the governor would name his successor. And the Grand Dragon of Indiana was the most likely choice to fill the seat, given what Jackson owed him. After that, as Stephenson told associates, “I’m going to be the biggest man in the United States.”

Outside, snow showers threatened, the wind was up, and the ground hard. Bare limbs of the big red maples and white oaks, native to this prairie soil, clattered against each other in skeletal gasps. The city was busting at its iron seams, the streets crowded with the clank and cacophony of autos, trolleys, and fine-dressed shoppers eying miracle appliances. Indiana was now as urban as it was rural; for the first time, half the population lived in a city. Many had grown up on farms where they’d pumped their own water, walked behind horse-drawn plows in the field, and rarely traveled more than a hundred miles from their place of birth. Now they had flush toilets and furnaces, toasters and telephones, vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, and the latest marvel: radios, bringing baseball games and music to a wooden box nesting in the family room.

Inside the snug interior of the new Italian Renaissance building, all was aglow with fellowship and praise. Bells rang, ushers shepherded men in tuxedos and white ties and women in evening gowns to their seats. A local writer, William Herschell, was summoned to read a poem he’d written, one of the most popular verses in the state, the closing line familiar to this crowd:

Ain’t God good to Indiana?

Ain’t He, fellers? Ain’t He, though?

The new governor was introduced to a rousing ovation. As secretary of state, Ed Jackson had authorized the Indiana charter of the Ku Klux Klan in 1921. And when he was exposed two years later as the highest-ranking elected official in Indiana to wear “the shroud of the terrorist and the mask of the highwayman,” as a crusading Irish American journalist put it, he shrugged it off. As did voters in the 1924 election. Jackson was one of us—a neighbor, son of a mill worker, war veteran, small town lawyer relatively new to the big city, a Disciples of Christ Protestant in good standing, not a shred of ethnicity to him.

When the grandchildren of these leading citizens later discovered hoods in the attic, or membership lists that included their kin, they could not fathom how such a thing came to pass. They knew the Ku Klux Klan was born in the murk of blood-spilling hate, built around a racial order that would find its most ghastly expression in the laws of Nazi Germany. They would tell themselves that the vast Klan of the American Midwest was nonviolent, casually cruel at worst, that its members were hayseeds and dupes and chuckleheads, that one twisted man with a surfeit of charisma had taken over the state without the consent of the majority.

None of it was true.

The Klan dens of the Heartland were not small or isolated or insignificant by any measure. Nor were their members ignorant of the power of their beliefs. They rose to their feet and cheered speakers who called Jews “un-American parasites.” They harassed and threatened Catholic clergy and nuns. They passed laws to prevent Black people from moving into their neighborhoods, going to public schools of their choice, or marrying people of another race. They voted overwhelmingly for the Klan slate in state and local elections. On occasion, they clubbed and terrified their enemies, or ran them out of town on a few hours’ notice. They bombed homes and set fires. They didn’t hide by day and only come out at night. They were people who held their communities together, bankers and merchants, lawyers and doctors, coaches and teachers, servants of God and shapers of opinion. Their wives belonged to the Klan women’s auxiliary, and their masked children marched in parades under the banner of the Ku Klux Kiddies.

“I did not sell the Klan in Indiana on hatreds,” Stephenson said. “I sold it on Americanism.” These people knew what they’d signed up for: that oath before God could not have been more specific about the absolute superiority of one race and one religion and the inferiority of all others.

A handful of Hoosiers were heroic—two rabbis, an African American publisher born enslaved, a fearless Catholic lawyer, a small-town editor repeatedly beaten and thrown in jail, a lone prosecutor. They were aided by a gifted man of letters, a Black poet and Broadway composer who forced an epic national political realignment with his eloquent defiance. Later, these resisters would be nudged from the margins of their time to history’s forefront. On this day, they were shut out completely from the orbit of power assembled around the new governor.

“We will stand for the things that are right at all times,” Jackson said now, to prolonged applause.

Stephenson settled into dinner at a table in the front of the ballroom. He was with a female companion, one of at least a dozen women he was seen with around town or at the lavish parties he threw inside his mansion. The term of the day was ladies’ man, for he was surely a charmer, a gift-giver, a note-sender, promiscuous with his praise of women he coveted. But he was much more than that. With an appetite for violent sexual excess, he needed to possess women, to hurt them and make them tremble. Of late, nothing seemed to satisfy him more than a naked woman bloodied by his teeth and begging for her life. His savagery was known only to a few people—it was the great secret of this multiloquent master of the North. But he showed no outward fear of getting caught; law enforcement couldn’t touch him. And because the Klan had made him rich, money further immunized him from justice. He earned far more in a year than Babe Ruth. He had a ninety-eight-foot yacht docked at Lake Erie and a private plane with the Klan logo painted underneath, to go with the fleet of luxury cars, a waterfront summer home, and the estate in the most prestigious address in Indiana. One of the men who traveled with him was known simply as “The Bank,” and carried enough cash to complete any favor on the spot.

Seated across from him tonight was someone he’d never met, Madge Oberholtzer. She was twenty-eight, daughter of a postal clerk, full-figured, with dark eyes and chestnut-colored hair that she usually wore in a stylish upsweep. Madge had attended Butler College in Irvington, the elegant neighborhood five miles east of downtown Indianapolis. She’d been a member of Pi Beta Phi sorority and fell in with a passionate group of college Hoosiers trying to get women the vote. She was high-spirited, with an infectious independent streak.

Today, she’d been hired to help set up the banquet, doing table assignments among other duties. She had taken a risk and acted with typical boldness when she seated herself across from the Grand Dragon. Who was Madge Oberholtzer to be at the great and powerful man’s table? She still lived with her parents. She’d taught public school for a while, then found a good-paying position with a state literacy program. But that job was on the chopping block. With a single command, Steve alone could fix her problem.

He asked Madge about herself. Her home was just four blocks from his palace of the Klan of the North. She’d walked by the German shepherds and armed guards, the Packards, Caddies, and Lexington Touring Cars, sometimes seeing disheveled revelers spilling out of the house at dawn. Steve himself was a college graduate, or so he said. Hoosier born and bred, he claimed, from an old South Bend family that made its old money in the oil business. Or maybe it was coal. Or banking. He told people he was a war hero, having served in France during the slaughter of the Great War. In business, he bragged of his Midas touch. “It doesn’t make any difference what I get into, it makes money for me.” His Klan had even tried to buy a college, Valparaiso, envisioning a Harvard of intolerance in the northeast corner of the state.

At the peak of his power, D. C. Stephenson wanted to wipe the dirt of the Midwest from his shoes. He would say goodbye to India-no-place, Naptown, as the swells in his circle called the capital city. This was the year to do it, depending on when that Senate seat opened. All that would stand between him and Klan control over much of the United States was Madge Oberholtzer. She would force a reckoning, a sensational trial of a man who’d enlisted countless Americans to take a pledge of hate. He asked her to dance. And later, he gave her his phone number: Irvington 0492.

___________________________________

Excerpted from A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Stopped Them, by Timothy Egan. Published by Viking Books. Copyright 2023. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.