Every story has to start somewhere.

And be somewhere.

Take Dennis Lehane’s 2003 novel, Mystic River. Its setting is so pivotal to the plot that you can find it right there in the title. As it happens, Mystic River is a real river in Massachusetts, coursing seven miles through the towns of Arlington, Somerville, Everett, Medford, Chelsea, Charlestown, and East Boston.

Each of those towns, like the river that flows through them, has a distinct history and identity, but Lehane conflated them into the fictional town of East Buckingham, where the story takes place. Even so, the urban grittiness of a working-class Boston neighborhood colors every page the novel, from scene descriptions to dialogue. The central mystery wouldn’t work without its cast of characters, who are mired in their community’s social mores and expectations. The setting not only informs their choices; it predicts their outcomes.

At some point, Lehane clearly decided to inject these richly drawn characters into a place that did not exist, while preserving the culture, customs, and accents of the Massachusetts towns that inspired it. East Buckingham feels real, right down to the studs, and that’s what matters. The result is a masterpiece of the mystery genre that uses setting as a central character.

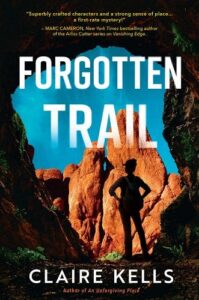

When it comes to the real versus the imagined, I’ve confronted that same dilemma in my own novels, which take place not in recognizable urban centers but in sprawling wilderness areas. There are sixty-three national parks in the United States, some of which attract millions of tourists each year. In a way then, this particular setting feels both accessible and exotic, catering to readers who want that sense of adventure in a familiar place.

While I can’t speak to Lehane’s choice to give his story a fictional backdrop, I can appreciate how difficult it is to capture the nuances of a real place while also trying to tell a compelling story. Readers who live in any of those seven towns along the Mystic River would have known, instantly, if a tiny detail wasn’t quite right. I’ve certainly had it happen to me, writing stories that take place in national parks. It isn’t so much the geography that matters, but other small details like ranger station locations, search-and-rescue squads, and policies regarding pets and dogs. If you’re going to put your characters in a real place, you better get it right.

For me, that process starts with a map. The National Geographic Society produces topographical trail maps of every national park in the U.S. in partnership with the National Park Service, or the NPS. These maps are an indispensable resource, as they include information about trail routes, points of interest, visitor sites, and recreation. All topographical maps include contour lines, which connect places that share the same altitude. When the lines are close together, that indicates a steep change in elevation; when farther apart, there is a more gradual slope. For me, contour lines never fail to bring a 2D map into three-dimensional focus.

I also use maps to identify key geographical features like mountains, lakes, and rivers. A fourteen-thousand-foot mountain in the Alaskan wilderness isn’t something a character can just hop over in a few hours, which all but eliminates a high-speed foot chase as a plot device. There is also a person’s individual fitness to consider; a seasoned park ranger might be able to complete a four-day hike in two, while a child might struggle to traverse the terrain at all.

To figure out what a fictional character can handle in the wilderness, I move from maps to real-life experiences. Photojournalists, bloggers, and social media users have taken advantage of modern technology to document their travels in vivid detail. A map can tell you how many miles it is from Point A to Point B, but only a human can tell you how long it took them to cover the distance. Some hikers use Naismith’s Rule, which estimates 19½ minutes per mile, plus 30 minutes for every 1,000 feet of ascent. There are online calculators that can fine-tune those estimates based on trail conditions and other factors. Photos and video often fill in the blanks.

While nothing beats the experience of actually being there, a picture is indeed worth a thousand words, especially when it comes to natural landscapes. A trail through the woods could be dirt, sand, rock, or overgrown brush. A river could be a trickling stream on a silt bed or high-speed rapids tumbling over limestone boulders. A wildflower meadow in late spring could be a massive snowdrift in winter. In researching specific locations within a national park, it always helps to know not just its topography, but its flora, fauna, and seasonality. Never again will I put a grizzly bear in Maine, for example.

Why, then, go to the trouble of using national parks as a backdrop? It would be easier, certainly, to create my own fictional wilderness, where I can make up my own pet policies and put a mountain where a lake should be. I worry, though, that doing that would take the reader out of the vivid, real-life experience of a wilderness mystery. It’s impossible to capture every detail of Alaska’s Gates of the Arctic National Park, for instance, but no reader would expect that. For a novel set in a small town north of Boston, those expectations are different.

In one of my books, set in Pinnacles National Park in California, the crime occurs at a fictional hike-in lodge. Compared to the rest of the series, this was a departure of sorts, but I was reluctant to have a murder take place at a storied destination like Skoki Lodge in Banff or Sperry Chalet in Glacier National Park. It felt too confining—and, admittedly, too risky. Having never been to those places, I worried about getting the details wrong.

Out in the wilderness, on the other hand, I feel like I’m venturing into the unknown while capturing the familiar. It’s not as good as going to Yosemite or Yellowstone, sure, but for this writer, it sometimes feels like the next best thing.