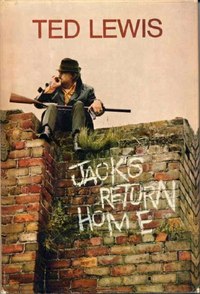

I can’t remember when I first heard of Mike Hodges’s seminal 1971 British gangster film, Get Carter, but it was long before I finally managed to see it late one night on cable television in a hotel in Prague in the late 1990s. And it was several more years until I was able to track down a copy of the then relatively rare source novel of the film, Ted Lewis’s Jack’s Return Home, published in 1970.

Until the last half decade or so, Get Carter as the book would subsequently be retitled and how it will be referred to it in this piece, along with Lewis’s eight other novels, were all out of print and little known. This is despite the praise heaped on them by luminaries such as David Peace, Dennis Lehane, Derek Raymond and James Sallis, for being formative in the creation of modern British noir. Get Carter and its two sequels, Jack Carter’s Law (1974) and Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon (1976) were reissued digitally and in paperback in 2014. Lewis’s other notable works, Plender (1971), and his last and probably darkest book, GBH (1980), have also been re-released. The film, starring Michael Caine in the title role, is now also easy to find.

The film adaptation premiered half a century ago on March 7th in the UK and in the US two weeks later on March 18th. Although a financial success, it received a lukewarm reception from critics, and languished until it attracted cult status with the “Cool Britannia” movement and the associated rise of gangster chic in the 1990s. The most prominent homage to Get Carter and the fashion and cadence of Britain’s 1960s underworld culture, Guy Ritchie’s 1998 film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, resulted in a slew of forgettable knock offs. There was even a CD released in 1999, Product of The Environment, in which notorious London underworld figures from the era performed spoken word stories to the music of British rapper Tricky.

The novel’s main character, Jack Carter, is an enforcer for a criminal organisation run by two brothers, Gerald and Les Fletcher. The story opens with Jack leaving London and traveling to the unnamed industrial working-class town in northern England where he grew up, to investigate the death of his estranged brother, Frank. Drunk on whisky, Frank drove his car off a cliff, an incident the police have labelled an accidental but which Jack, aware his brother never touched alcohol, views more suspiciously. As Jack puts it: “They hadn’t even bothered to be careful; they hadn’t even bothered to be clever.” Jack proceeds to take apart ‘they’, the organisation that runs the town’s criminal activities, which he holds responsible for his brother’s death, culminating in a violent and ambiguous ending.

Other key characters include Kinnear, the local crime lord, Margaret, Frank’s mistress, and his brother’s teenage daughter, Doreen, who it is clearly implied is actually Jack’s daughter from a drunken fling he had with Frank’s wife and the reason for the brother’s estrangement. The follow up novels are both prequels and decline in quality with each instalment. Jack Carter’s Law is set in London’s vice district of Soho and sees Jack attempting to track down a criminal informant who has information that could put his bosses in jail, at the same time as carrying on an affair with Audrey, Gerald’s wife and plotting to rip off his employers. Jack Carter and the Mafia Pidgeon almost completely plays it for laughs with a story about Jack being dispatched to a villa in Spain to bodyguard a Mafia informant.

Lewis’s biographer Nick Triplow has asserted the ground-breaking nature of the first Jack Carter book lies in its depiction of a different kind of literary criminal, more cunning, ruthless and violent. The setting was different from much that had come before, a grim northern England industrial town, and Lewis infused the story with a razor-sharp analysis of the shifting political economy of organised crime in the UK as the 1960s ended. Linked to this, the novel captures the shifting class changes under way as the UK moved into the 1970s, when post-war austerity crossed over into economic prosperity and along with it, developments such as sexual liberation gradually crept into the regions.

The film version was shot in 40 days at a total cost of US$750,000. Producer Michael Klinger, whose CV had included the Roman Polanski films Repulsion (1965—for which he was uncredited) and Cul-De-Sac (1966), as well as the risqué exploitation documentary Primitive London (1965), wanted to capitalise on significant public interest generated by the trial of the real-life gangland duo, Ronald and Reginald Kray (the inspiration for Jack’s thoroughly nouveau riche gangster bosses, the Fletchers). Klinger asked Hodges, who until then had only worked in television, to direct. Hodges kept the basic story of Lewis’s book and much of the dialogue and removed the rest. The setting became the industrial centre of Newcastle (or Newcastle Upon Tyne, as it is now known). Jack’s relationship with Doreen is merely hinted at, and Jack’s fate at the end is made clear when he is killed by an assassin, presumably operating at the behest of the Fletchers.

A relatively straight forward revenge story, the film’s narrative power derives from the collision between the grim working-class world of Jack’s youth and modern 1970s Britain. If anything, it is even tougher than the book. Scenes such as Jack throwing a businessman from an elevated carpark, and his reaction to discovering Doreen has been coerced into appearing in a porn film, still pack emotional punch. The uniformly bleak northern setting is infused with Hodges’s experience as a conscript in the Royal Navy in the late 1950s, during which time he regularly docked at tough, impoverished northern port towns.

This verisimilitude is further enhanced by Caine, who claimed to have based Jack’s character on a London gangland figure he knew, “dress, attitude, frame of mind, talk—even the walk”. There are also resemblances to Lewis’s life; a fondness for booze and cigarettes, habits which would eventually kill him at the age of just forty-two, and time spent rubbing up against unsavoury aspects of British society. As Triplow put it to me in a 2020 interview: ‘There’s enough autobiographical detail in there to suggest he [Lewis] was weaving his own experience through the narrative. He was working in Soho in the lead up to writing Carter and rubbing shoulders with minor villains in various pubs and clubs. His friend and colleague, Tom Barling, introduced him to his own underworld connections. Exactly how far he took those associations, who knows? There are different versions. But it’s worth bearing in mind that ever since he was a kid, Lewis had always been drawn towards taking risks.’

In his 2014 study of British crime cinema, Paul Elliott states: ‘The British gangster film may often be unfavourably compared with its Hollywood cousin but in its depiction of evolving notions of masculinity, its discussion of social anxieties and its exposition of nationality, it is a valuable mirror to a Britain that is both fascinated and repulsed by its dark past.’ He further notes that the ‘iconography of Get Carter (the suit, the shotgun, the beer in the thin glass) have become cliches of British crime cinema and arguably served to obscure and overstate the film’s importance in the development of the form.’

While Get Carter was by no means the first and is probably not even the best British gangster film, it is certainly among the most influential.

The lineage of British gangster cinema stretches back to the 1930s but was given its first full blooded treatment in a cycle of three post war films that drew condemnation from censors, moralists and film critics for their depiction of sex and violence and their bleak take on post-war British life: They Made Me a Fugitive (1947) or I Became a Criminal, the title it was known by in the US, No Orchids for Miss Blandish, and Brighton Rock (both of which appeared in 1948). Other prominent entries include Joseph Losey’s The Criminal (1960) and Peter Yates’s dramatization of the Great Train Robbery, Robbery (1967). Both films starred Stanley Baker, who was instrumental in bringing a tougher, glamorous but also more working-class version of British criminality to the big screen. As Elliot points out, Get Carter was itself part of loose cycle of three prominent early 1970s British gangland films, sandwiched between the counterculture influenced Performance (1970) and Michael Tuchner’s viscerally nasty Villain (1971). Get Carter’s British cinematic influences were supplemented by a wider cross pollination, American film noir and films like John Boorman’s 1967 movie Point Blank, which Lewis was a major fan of.

Get Carter feeds into another key strand of British gangster cinema, the criminal as hungry entrepreneur, a trait made more overt in Villain’s central character, Vic Dakin, a gay, psychopathic right-wing gangster, and reaching its apotheosis, a year after Margaret Thatcher took power in 1979, in Bob Hoskin’s 1980 portrayal of Harold Shand in John MacKenzie’s The Long Good Friday.

MGM commissioned director George Armitage to give Get Carter a blaxsploitation overlay, resulting in the 1972 film, Hit Man, about a black assassin who travels to Southern California for the funeral of his brother and becomes obsessed with tracking down the individuals responsible for his death. Hodges’s effort was also remade as an entirely unremarkable film in 2000 starring Sylvester Stallone.

Get Carter has been credited as a key influence in the popular 1970s British television crime show The Sweeney, which featured two tough, rule breaking police detectives. In addition to those already namechecked—Villain, The Long Good Friday, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and its various imitators—strong trace elements of Get Carter can be found in Michael Apted’s little known The Squeeze (1977), Stephen Frears’s The Hit (1984), Jonathan Glazer’s Sexy Beast (2000), and Shane Meadow’s Dead Man’s Shoes (2004). Sexy Beast and its depiction of retired working-class British gangsters living in sun drenched retirement in Spain, can almost be viewed as a parallel cinematic world for Jack Carter, had he lived long enough.