When I was dreaming up the plot of my latest young adult thriller, The Revenge Game, I posed the following research question to my social media followers: “It’s hard to phrase, but did you ever experience kids at school/camp participating in, like, sexual conquest competitions? Example: at my camp, the *cool kids* would rank the hottest people and compete to see who could hook up with the most names on the list.”

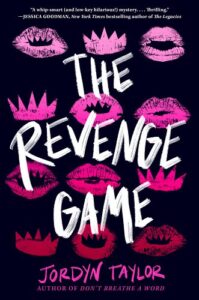

Before I’d decided who my main characters were, or what exactly would happen to them, I knew The Revenge Game needed to involve a secret competition for sexual prowess among the boys at a newly co-ed boarding school. In battling it out for sexual supremacy, the boys would also be jockeying for power—for who has the most perceived masculinity. Because every good mystery novel needs high stakes, and for whom are the stakes higher than a young man who feels that his masculinity might be in question?

A friend responded to my social media post, explaining that at her friend’s summer camp, the kids had maintained a points system to keep track of who got the most action. And that’s how the King’s Cup—the secret competition that spurs the action in The Revenge Game—was born.

From pop culture to religion to academic and workplace norms, men are taught that the stronger they are, the more worthy they are as human beings. While it’s great that some men want to prioritize self-improvement—shoutout to every dude who’s been to therapy!—some men go to disturbing lengths so as not to seem weak, and end up harming themselves and others. We refer to this unhealthy, dangerous behavior as “toxic masculinity,” a term that originated in men’s movements of the 1980s but has seen a resurgence in recent years, especially around the #MeToo movement.

In my work as an editor at Men’s Health, I’ve covered stories of men who end up hospitalized because they’ve pushed themselves too hard at the gym, followed too restrictive of a diet, or taken dangerous (sometimes deadly) performance-enhancing supplements, all in pursuit of the ideal jacked or shredded male form. The suicide rate is around four times higher for men than it is for women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and, as research has shown, that’s partly because men are less likely to talk about and seek help for mental health issues.

I’ve also covered stories about the harm men do to others: about the men who refuse to take no for an answer and who lash out with violence when faced with rejection. I open The Revenge Game with a chilling quote from the great Margaret Atwood: “Men are afraid women will laugh at them. Women are afraid men will kill them.” If that quote sounds extreme, consider the college student who killed six people and wounded thirteen more in a fit of rage over women’s romantic rejections, or the man accused of shooting and killing his coworker after she rejected his advances, or the airport worker found guilty of murdering the boyfriend of a work crush who had turned him down, or the man who shot a killed a woman who rejected him at a bar. There are many, many more disturbing examples where those came from.

In The Revenge Game, when the girls at Sullivan-Stewart Preparatory School realize they’re being preyed on, they use what they know of toxic masculinity to get back at the boys. They form their own secret competition called the Queen’s Cup, where the goal is to reject the guys in as many humiliating ways as possible. Of course, the more humiliated the boys become, the more desperate they are to prove themselves, which leads to increasingly harmful behavior. And the worse they behave, the more the girls want to strike back at them. That tension keeps building before it eventually erupts in a dramatic climax on prom night.

But toxic masculinity is so much more than a plot device in The Revenge Game. Young adult books are a place for teens to explore the world safely and figure out what kind of person they want to be in the world.

In writing a feminist mystery, my hope is that The Revenge Game is a source of inspiration to teen readers of all genders. I stress the word all because feminism isn’t about hating men; it’s about advocating for everyone to be treated equally. Men and boys can fight for gender equality, too. The Revenge Game shows what that activism can look like. One of my favorite characters is Sam, a guy who posts about mental health on social media and who volunteers to take notes during a meeting for a group project—an administrative task that people often expect women to handle. Sam also speaks up in a big way . . . but you’ll have to read the book to find out how.

I know there are lots of good-hearted guys out there who want to be like Sam, but they might need help to get there. I get that. Let me tell you: It’s freakin’ hard to push back against the patriarchy. But I’m hopeful for men, just like I’m hopeful for all the young readers who might see themselves reflected in The Revenge Game.

The #MeToo movement helped tear down old pillars of toxic masculinity. Now it’s time to rebuild our world for the better, and young adult fiction can be part of that journey of progress.

***