When you tell people you are going to Fiji to research and write a book, they imagine you sitting under a palm tree on a beach of pure white sand, sipping gin cocktails and scribbling into a notebook as the sun sets in spectacular orange and pink hues over the horizon. My family is from Fiji, so I had spent some time there in my youth. My experience of the country had largely run to pothole-filled roads and the humble houses of my extended family, but as a budding novelist I wasn’t going to allow this small detail to impinge on the fantasy. I made my plans, two months in Fiji in 2016 to research and write. Over the next nine years, over the course of two books, I would go back twice. Was the reality anything like the fantasy? Spoiler: of course not. Let me tell you about some of the challenges and highlights of researching in a country like Fiji.

I’ll start with a little background on the country of my birth, for those who aren’t familiar with it. Fiji is an archipelago of over 300 islands in the South Pacific. The weather is tropical which is mostly lovely except for the mosquitos and occasional devastating cyclone. Blue Lagoon, Castaway and Survivor S14 were all shot in Fiji.

Now you might be looking at my name and thinking, that sounds Indian. And indeed it is. So how did I come to be born in Fiji? According to the last census in 2016, 37.5% of the population of Fiji is of Indian ethnicity. Why is this, you may ask? Look no further than the good old British empire. The Fijian chief Cakobau ceded Fiji over to Britian in 1874, apparently to pay some debts owed to the American navy. I guess that’s as good a reason as any other to give up your sovereignty?

The Indian government of the time, still part of the British empire, had established an indentured servitude program, sending Indians out to colonies all over the world, to places such as Mauritius, Trinidad and Jamaica. When the sugar plantations of Fiji needed workers and the British governor of Fiji didn’t want to interfere with the native population’s way of life, the decision was made to import cheap labour from India. From 1879 to 1916, over 60,000 Indians came to Fiji as indentured servants, or girmityas. About half of them cashed in their return trip to India, leaving about 30,000 to start a new life in Fiji.

The Sergeant Akal Singh series is set in the early 1900s and is focussed on the experiences of the Indian indentured labourers (through the vehicle of a crime fiction romp that you can read on the beach, lest this all seem too serious). This is the time of my great grandparents, who passed away before I was born. To my knowledge, by the time I came to do this research, there was nobody left who could tell me of their lived experience of indenture. Almost all of the girmityas were illiterate, their stories were rarely written down. There is an academic term for this phenomenon, which extends to many groups under colonial systems—the subaltern voice, which refers to the voices of marginalised and oppressed groups, rendered inaudible within dominant power structures.

I easily found information on the rules and regulations governing the lives of the girmityas. But what I learned of their daily lives largely came from observations made by Europeans. Religious missionaries, the Fiji Times journalists, reports in government gazettes written by British colonial administrators. It made what I was trying to do harder, but it also gave me a greater urgency to write this novel – to give voice, even if it was a posthumous, fictional and almost certainly flawed voice, to people who hadn’t had a well recorded voice in their lifetimes.

The next topic I found challenging to research was the culture of the iTaukei people—the Indigenous people of Fiji. I was confronted with my own lack of knowledge of the Indigenous culture of my place of birth. When we spent time there when I was younger, Fiji was quite a segregated society, so we didn’t have a lot of contact with iTaukei people. This happily seems to be changing.

I read what I could at libraries in Australia and at the University of the South Pacific (USP), about political hierarchies, the meanings of various ceremonies and how marriages were arranged. But what I really wanted was to spend some time at a Fijian village. Not on a touristy jaunt where handsome iTaukei men in ceremonial garb performed ceremonies out of context, but to witness daily life in a village. This was met with scepticism by my family. None of them, who had lived in Fiji for much of their lives, had ever stayed in a village. Questions were raised around safety, comfort and the value I would get from this exercise. But finally, persistence paid off. Through a distant family connection (my cousin’s cousin’s niece’s aunt – which sounds nonsensical but is a connection that makes sense in Fiji), I was able to organise a stay at the village of Lovoni.

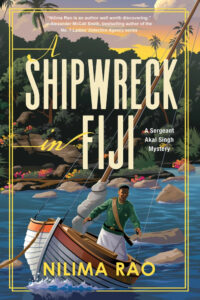

Lovoni is on the island of Ovalau, which is the setting of my second novel, A Shipwreck in Fiji. Ovalau is an extinct volcano, roughly circular, with a narrow strip of land and beach around a ring of cliffs. In the middle of the cliffs is a valley, with the village of Lovoni at the bottom. The main town on the island is Levuka, a lovely port town on the eastern side of the island, which was the original capital of the colony of Fiji. Levuka has a fascinating history full of pirates and cannons and secret societies. Because of the topography of Ovalau, Levuka quickly ran out of space to grow, so the capital was moved to Suva in 1877. The economy of the island is now based on a tuna cannery, which brings in workers, mostly women, from all the villages across Ovalau.

The journey from Melbourne to Lovoni consisted of a five-hour flight to Nadi, a five-hour bus ride to Suva, a two-hour bus ride to a wharf in the middle of nowhere, a three-hour ferry journey to Levuka and finally a forty-five-minute truck journey.

The truck journey was an experience unto itself. It was the daily commute for the workers from the cannery, one service in the morning stopping at all the villages, and one service home in the evening. The vehicle was a pick-up truck with canvas walls and roof over the tray, and benches along the two long sides. I was on a bench, cheek by jowl with my host, Joanne, on one side and one of the ladies from the cannery on the other. If you missed out on a bench seat, you sat on the floor in between the benches, alongside luggage, boxes and buckets. One passenger was nonchalantly hanging off the end of the truck, with a suitcase in one hand. All as we juddered along rocky dirt tracks, up the steep hill of the crater and down into the valley, through shallow streams, never showing an ounce of concern.

My first glimpse of the Lovoni Valley took my breath away. The valley is covered in lush, dense forest, with giant ferns, tall trees draped with vines silhouetted against the sky and an incredible array of glossy leaved plants climbing up the edge of the crater. And once you were over the edge of the crater, all you could see was forest-covered cliffs surrounding you, and then, sky. It was as though the rest of the world didn’t exist. Once I recovered from my initial awe, I found myself humming the Jurassic Park theme and looking for Pterodactyls in the sky.

I had an incredible twenty-four hours in Lovoni. The evening was spent with my host’s extended family, sitting on the floor on imbi, the traditional mats, helping prepare leaves to be woven into more imbi and eating otha, ferns cooked in coconut milk with boiled taro. I drank kava, the mild narcotic drink commonly drunk in Fiji, which is also part of many traditional iTaukei ceremonies. The chief of the village performed a traditional welcome ceremony, which meant I was accepted as a visitor to the village.

The next day, Joanne showed me around the village and told me the history of the Lovoni people. I met locals who made me feel so welcome, as though I had always been there but had just forgotten. One of the local ladies gifted me with home grown mushrooms and I garnered at least two marriage proposals. One of the highlights was swimming with the children in the river that runs through the valley and watching as they constructed a bilibili, a traditional raft, and floated around on it. It wasn’t the most robust, but it was an exceptional effort for how quickly they put it together with only the materials around them. The visit was everything I had hoped for and so much more. I felt like I had some basis for writing scenes set in a village. And I felt closer to Fiji than I ever had before.

You will notice that I didn’t mention a beach once. There may have been some gin cocktails on occasion, but it was the exception rather than the rule. So no, the reality was nothing like the fantasy. It was sometimes frustrating but always fascinating. The act of researching and writing these books has required me to be brave in ways I find astonishing even now. Now … where to set the next book? (Kidding, it’s Fiji!)

***