“From the purely tactical point of view, women were able to move about without exciting so much suspicion as men and were therefore exceedingly useful to us…”

—Maurice Buckmaster, They Fought Alone: The Story of British Agents in France

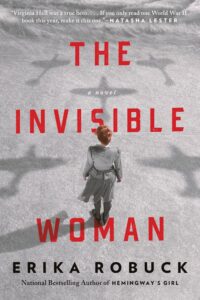

While researching my latest novel, The Invisible Woman, about Allied spy Virginia Hall, I made a surprising discovery. Nazis largely didn’t think women were as brave, intelligent, and even devious and vengeful as men. Because of this, women were often overlooked in the hunt for resistors and spies.

German propaganda at the time depicted a feminine ideal of woman as mother, preferably of four or more children, tending home quietly and with docility. How surprised Gestapo chief Klaus Barbie, “The Butcher of Lyon,” was to discover one of the most troublesome resistors in his region was not only a woman, but a woman with a prosthetic leg.

Barbie christened Virginia Hall “La Dame qui Boite (The Lady who Limps), Most Dangerous of Allied Spies” and put her face on wanted posters. Little did he know she was just one of many women operating in the shadows to destroy the Nazis—women whose stories would be unbelievable if they weren’t true.

***

Noor Inayat Kahn

Born in 1914 in Moscow to an American mother and an Indian father, Noor grew up across the globe, but mostly in France. She was a pacifist, a writer of children’s books, and a descendent of an 18th century Muslim ruler. After the fall of France, her family escaped to London. As a bilingual member of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, she was recruited for the British clandestine service, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The first female wireless operator (WO) sent to Occupied France she went in spite of knowing WOs had a life expectancy of six weeks behind enemy lines.

After her network was compromised, HQ urged Noor to return to London, but she was the last WO left standing in her region and she refused to abandon her post. She managed to continue for four months before being betrayed by a Frenchwoman. Noor was deported to a German prison, was tortured, and was ultimately executed at Dachau Concentration Camp. She was posthumously awarded France’s Croix de Guerre and Britain’s George Cross.

Josephine Baker

Born in 1906 in Missouri, Josephine Baker joined a vaudeville act in her teens, but racism in the US sent her to France, where segregation didn’t exist on the same scale as it did at home. Her fearless, erotic performances in Paris propelled her to massive stardom, and she became one of the wealthiest and most celebrated performers in Europe. When war broke out, she hid refugees and resistors in her chateau, and helped procure false papers for their escapes.

Her job as a performer allowed her to travel, and she gathered intelligence at Axis functions for the Allies, recording what she learned on sheet music with invisible ink. When the Nazis heard rumors of her activity and started to close in, she was evacuated to London. For her service, General de Gaulle awarded Baker the Rosette de la Résistance, the Croix de Guerre, and named her a Chevalier de Légion d’honneur.

Micheline Dumon

Born in Brussels in 1921, Micheline Dumon and her family were in the Belgian Resistance. They started The Comet Line, an escape and evasion network for downed Allied aviators that ran from Belgium, through France, and into Spain. When her parents and younger sister, Andrée, were arrested due to a betrayer, Micheline took over leadership, even escorting and guiding pilots over the Pyrenees on many trips.

She was arrested and questioned on multiple occasions, but because she looked so young—she could pass for a thirteen-year-old—and could call forth the tears to support her alleged age, she was released. Throughout the war, Micheline searched for the betrayer, and eventually helped in his capture. She personally escorted 250 aviators, and nearly 800 in total were saved on The Comet Line. After the war, Dumon was decorated with the George Medal and the US Medal of Freedom.

Violette Szabo

Born in France in 1921 to a French mother and a British father, Violette grew up between the two countries, with France as her first love. After escaping France with her little brother as it fell to the Nazis, she joined the rest of her family in London. On Bastille Day, 1940, Violette’s mother asked Violette to find and invite an exiled French soldier to dinner. That man was French Legionnaire Etienne Szabo, and he and Violette fell in love. Married after a five-week courtship, Violette became pregnant while Etienne was on leave, and gave birth to her daughter, Tania, in July of 1942. In October of ’42, Etienne was killed in the Battle of El Alamein in North Africa, having never set eyes on his little girl.

Fueled by a wish to serve and a need for vengeance, and as a bilingual sharpshooter and member of both the Land Army and the Auxiliary Territorial Service, Violette was recruited to join the SOE. She parachuted into Occupied France on two missions but was arrested shortly into the second, just after D-Day, after a shootout resulted in the death of at least one Nazi. She was imprisoned in France before deportation to Ravensbrück Concentration Camp in Germany and was executed there in February of 1945.

In 1947, King George himself pinned little Tania with Violette’s posthumous George Cross award, and Tania received her mother’s Croix de Guerre from the French Ambassador two years later.

Virginia Hall

I don’t want to reveal too much about Virginia Hall, only that if I’d made up a story about a woman with a prosthetic leg, wanted by the Gestapo, who escaped Nazi Occupied France over the snow-covered Pyrenees, only to return weeks before D-Day as a wireless operator, arming and training guerrilla fighters while hunting her first network’s betrayer, you wouldn’t believe it.

If you’d like to learn more about Hall, perhaps you’ll pick up a copy of The Invisible Woman.

***