Fall is one of my favorite times to read, whether I’m catching the last hot afternoon under a tree or cozying up with a warm beverage while the frost sets in outside. And this year, with the encroaching sense of horror making it seem like spooky season decided to come early in real life, I’ve been desperately on the lookout for books that will give my imagination a real workout—books with a world that challenges and envelops me, offering an escape from—and sometimes, even, a possible way through—the winds of change that are blowing all around us.

If you’re like me, you’re in luck; this fall offers plenty of speculative worlds to stretch out or curl up with. These five autumn reads took me from the melting northern permafrost to the icebergs of Antarctica—from bog-preserved parchment maps to robot battles in outer space—while reaffirming the inherent value of humanity as something worth protecting, no matter the world around us.

Yume Kitasei, Saltcrop

(Flatiron)

Yume Kitasei’s Saltcrop (9/30) is a fantastic book of hopeful dystopia, equal parts ecological thriller and intimate family portrait. Featuring seaspray, corporate treachery, a post-climate-apocalypse future that feels all too near, and a beloved boat named Bumblebee, this book explores all the ways family accidentally defines us. When Skipper and Carmen decide to go in search of their older sister, they do not know whether Nora has fallen out of touch due to thoughtlessness or something more sinister. As they follow Skipper’s uneasy gut feeling all the way up to the arctic permafrost, it becomes clear that Nora’s disappearance is only a small part of a conspiracy profiting from the food insecurity that has wracked their lives for as long as they can remember. The book is narrated by all three sisters, and combines a plot that does not stop and the deeply literary joy of seeing how they both misinterpret and define each other. I couldn’t put this one down.

Nghi Vo, A Mouthful of Dust

(Tordotcom)

Nghi Vo’s gentle yet courageous Cleric Chih returns in A Mouthful of Dust (10/7), the sixth installment in her Singing Hills series. This book brings everything fans of the series will be hoping for—the world rich in details, clear and compelling characterization, the smallest dash of horror to spice things up—while standing beautifully on its own. On their way to document the effects of a long-past famine in Baolin, Cleric Chih and their memory-spirit neixin Almost Brilliant stumble on a mysterious jawbone. The local leader is less than forthcoming about the events during the worst of the starvation, and Cleric Chih cannot shake the sense that his reticence may have something to do with the poorly-buried body they had found—but how to untangle the mystery of what happened when the powers-that-be are desperate for the past to remain interred? At a moment when history is being rewritten in front of our very eyes, Chih’s dedication to witnessing and documenting past atrocities—in spite of the risks they must take to do so, and their own doubts about its efficacy—feels terrifyingly timely.

Anna North, Bog Queen

(Bloomsbury Publishing)

Anna North’s Bog Queen (10/14) is as complex and tightly woven as the peat moss that sometimes narrates the action. A braided tale of a forensic anthropologist, a long-dead druid, and a bog, this curious book takes a hatchet to our expectations of genre, people, and what is possible. Agnes has come to Manchester from the United States in part because it was the only postdoc available for a forensic anthropologist, but also to prove to her loving—if overbearing—family back home that she can survive on her own. Up against the end of her term, with no further job lined up, she is called to investigate an uncannily preserved body pulled from the peat; unbeknownst to her, her advocacy for the dead woman will force her to confront her own preconceptions about the limits of what she can do. This book is at once a mystery that constantly short-circuits the beats of the genre, and an exquisitely drawn portrait of two women whose strangeness cannot be extricated from their unstoppable ability to shift the world around them.

Quan Barry, The Unveiling

(Grove)

The world of Quan Barry’s The Unveiling (10/14) is dizzying, its reality capable of melting and reforming like ice under the blade of a skate. The book brims with ominous portents, atmospheric dread, and Barry’s sharp humor. Striker is a Black location scout on an Antarctic luxury cruise, surrounded by wealthy, mostly white tourists. She has doubts about her own motivations in accepting the work assignment—at the end of the world and over Christmas—even before disaster strikes and the tourists find themselves marooned on a volcanic island. As ancient mysteries emerge from the Antarctic ice, Striker must face parts of her past that threaten to undo her very self. This book will have you waking in a cold sweat from nightmares of icebergs and mirror-still sea, fearful of guilty horrors emerging from the melting permafrost. Barry writes with the poet’s ability to animate an entire novel with a single dire truth.

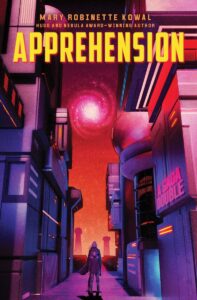

Sam J. Miller, Mary Robinette Kowal, Red Star Hustle/Apprehension

(Saga Double)

The Saga Double Red Star Hustle/Apprehension (10/21) offers two short noirs—a novel by Sam J. Miller and a novella by Mary Robinette Kowal—in a single volume. Red Star Hustle sings with tension as its two protagonists play cat-and-mouse in a murder case that threatens to upend galactic order, but never loses sight of the humanity of any of its characters. At once a nail-biting ride through an exciting universe and a paean to hope for recovery from addiction, Miller’s keen eye for character and deft hand at worldbuilding make for a story that carries more of a punch than should be legal in a novel this short. Mary Robinette Kowal’s Apprehension follows Bonnyjean, a seventy-eight-year-old retiree on vacation with her son-in-law and grandson, as she returns to the site of her service as a special forces operative seeking relief from the grief that has paralyzed her family in the year since her daughter’s death. Tightly plotted and shamelessly heartfelt, it is a joy to read a noir protagonized by an older woman which neither erases her aging body nor reduces her agency because of it.