A crime as large as a war may exceed the definition of crime in the usual sense. Crime is bad enough when it’s one or a few victims and one or a few perpetrators. That kind of crime, though reprehensible, one can get arms around while often cringing in horror or disbelief. But how does one reach understanding of crimes, now called ‘against humanity,’ where there are millions of victims and millions, if not perpetrators, accessories to the facts?

Perhaps that is why war stories seem never to go out of fashion. No matter how much one learns or knows, one is ultimately left back at the beginning of the search, wondering how could this have happened? As Ben Ferencz commented after prosecuting the Nuremberg Trials following World War II, most of the Germans (in both world wars) were not monsters or devils incarnate. They were just average people one could easily imagine as next-door neighbors, caught in a rip current of history that swept them violently along. I find that most terrifying! Maybe the real question should be: what are we each capable of?

So here are five novels centered around war, mostly the Second World War, that focus on the crimes of the millions, both victims and perpetrators/accessories, into the small personal stories of individuals caught in the rip currents. This recalls Writing School 101, expertly done. Take the incomprehensible and make it personal through characters people either love or love to hate, or those they cannot look away from. Let those characters make the unfathomable points, one by one, until at least some of the enormity is chipped away. Perhaps a new perspective results for at least one aspect of ‘how this could happen.’ And is happening. And will undoubtedly continue to happen.

Winds of War and War and Remembrance, Herman Wouk

These two novels carry a reader from that bravado of young men entering the Second World War as the US gets involved to ultimate triumph over the Axis by war’s end. But the harrowing journey is principally revealed through two families. One a US naval officer’s and the other, an intellectual Jewish family caught in Europe as war closes in around them. Their personal doubts and struggles, successes and failures, terror and acceptance lead readers through their tragedies and the profound discoveries made about themselves, the world, and the beliefs that underlie it all. German military strategy, from the initial belief to the ultimate failure under the infallible Fuhrer whom they could not question, are also disclosed, as are American isolationist politics of the times.

The English Patient, Michael Ondaatje

It might be obvious that I love large, sweeping epics that carry one through time and lots of geographical space. All great books to me are a vacation. This novel’s view of invading and retaking Italy during WWII is gloriously portrayed in the unexpected romance between a nurse and a bomb-defusing specialist. While the nurse cares for a terminal (English) patient, the couple attempts to eek out life amid the chaos, danger, and ruins, knowing any moment could be the last. Thus, each moment they have becomes precious to the reader as well, in their terror and utter beauty.

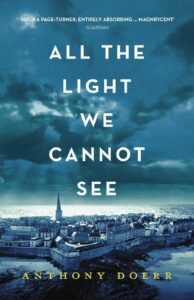

All the Light We Cannot See, Anthony Doerr

A slice of WWII told through two youngsters on opposite sides of the war—one a blind girl in Brittany, France, the other a young male orphan with an intuitive comprehension of the new radio technology that informs the conflict. The two connect through those invisible radio waves that represent the ephemeral cord between two young people caught by circumstances neither understands nor controls. In both its innocence and scientific possibility, the story is poignantly beautiful.

*