Unreliable narrators surprise readers with unexpected trajectories, sleight of hands and new ways of understanding the human condition. What makes them so fascinating is not only their complex psychological tapestries, but the ways in which we return to these characters to unpack the mysteries they possess. Here are some revelatory characters from five astounding books.

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

The story charts the misadventures of a Black man attempting to find his place in society. We never know the name of the male protagonist in Ellison’s masterpiece. Along with the title and the naïve voice earlier in the novel, this creates a subtle sense of non-belonging. This sensibility of elements of existence remaining unidentified is a thread. We are never told the name of the state where the protagonist attends college, the name of the college, or his given names at hospitals. This further cements his invisible status within a system designed to work against him. The narrator is also the protagonist telling the story in hindsight as a memoir, creating a sense of separation between narrator and protagonist, although they are the same person.

Before the main character joins The Brotherhood, he is innocent, often misinterpreting situations. This forces readers to make their own conclusions beyond his judgements to see Ellison’s true intentions. The use of first-person narration brings us into the internal landscapes of his character; by default, often limiting the consciousness of other characters. The juxtaposition of his role as a servile Black man in the earlier chapters and his position later as a political talking head for The Brotherhood show the arc of his character. His voice changes as he begins to reconcile with the realization that his societal role as a Black man limits his sense of individuality, forcing him to wear the mask of invisibility to disrupt and survive structural injustices.

The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector

In Lispector’s astonishing novel, the disintegration of the self is the central focus. The Hour of the Star is a clever example of literary slow horror in which the fictional male protagonist, a writer named Rodrigo S.M., tells the urgent story of Macabea, a woman so erased that she is unaware of her supposed irrelevance until a devastation occurs. Macabea is a nineteen-year-old typist living on the fringes of Rio di Janeiro. When she falls for a cruel man, disaster happens. She loses her job, seeks the council of a fortune teller and in so doing seals her fate.

In telling her story, Rodrigo assesses her life in ways that feel both tender and judgmental. He sometimes interrupts the text to reflect and question his own motivations. Despite his conclusion that she is ‘unremarkable’, he makes the effort to hold a lens up to her life and in doing so contradicts that conclusion. He cannot look away from her existence, from the painful aspects that reverberate into his consciousness. This layering of narrators, of voice, makes this novel not only a radical work but an experience that feels like holding one’s breath. Ingrained within the text and the unreliable narrators is a sense of urgency, made even more poignant considering Lispector wrote the book in a few months then died shortly afterwards. It forces us as readers to turn the gaze to ourselves, to those around us, interrogating the ways we make people feel seen or erased.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

Shirley Jackson’s sublimely strange offering introduces the audience to its narrator ‘Merricat’ with one of the most iconic literary openings ever. “My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had.”

Merricat’s voice appears childlike and innocent, but it is not. Her thoughts and actions reveal a fiendishly psychologically disturbed, possibly dangerous person. She is intensely obsessive and protective over her sister Constance. This along with her desire to isolate them from outside influence distorts her perspective on the world. It is difficult for the reader to trust Merricat’s account of events in the story due to her skewed mindset, particularly the poisoning of her family, one of the most critical occurrences. Her narration toys with the facts, her tendency to omit information along with justifying her behaviour therefore making the audience unclear about the extent of her culpability. Merricat remains a singular voice in fiction; peculiar, mesmeric and filled with warped fantasies.

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

A gothic masterclass on the hidden tensions of a union and the mental unravelling that can happen as a result. This eerie, propulsive classic is about the secrets locked within the dark heart of a marriage as the second Mrs de Winter, newly married to Maxim, attempts to discover what happened to his first wife, the idealized, pedestalled Rebecca. The new Mrs de Winter is young and inexperienced in the social classes. She is an unreliable narrator because she often misinterprets her surroundings, Manderley which looms large in the novel. She is intimidated by this world and the memory of Rebecca. The first wife who appears glamorous and more suited to Max even in absence. These insecurities make her see things not as they are but how she perceives them to be. Both Maxim and Mrs Danvers often mislead her causing Mrs de Winter to question their motivations. In response, she projects her insecurities about the marriage onto others. As the novel progresses, Mrs de Winter’s narration feels like a series of slipstreams, as if she is falling into an abyss she unwittingly creates. Her paranoia and anxiety riddled voice is one of the reasons this atmospheric book occupies its own unique space in fiction.

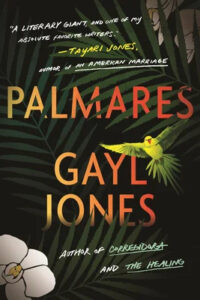

Palmares by Gayl Jones

In this magnificent, hallucinatory novel the ever-enigmatic Jones reimagines a historical setting where Almeyda, the narrator, a former slave from 17th century Brazil, tells the story retrospectively of her escapades both within and outside of the illusive Palmares. Palmares is a free colony for African people who escape slavery. During her childhood, Almeyda lives with her mother and grandmother who practice with herbal medicines and charms. Almeyda has a traumatic, painful past as a slave. Her husband disappears. Her subsequent search for him is part of the narrative. After she breaks out beyond the confines of Palmares, she discovers her own powers. As a narrator, Almeyda gives lots of detail and specificity about her story. This makes the reading experience rich and compelling. This is not an easy read, the horrors she experiences as a slave in her former home never feel far removed from her present life. Almeyda telling her story retrospectively also adds another layer of unreliability. Her voice is indelible in this mesmerizing tale replete with visions, witches, dreamlike characters and medicine men calling to ancestors carrying Almeyda and we as readers along through this mythical world.

***