Poirot beamed approval on her. “Now, first of all, what is your own idea? You are a girl of remarkable intelligence. That can be seen at once! What is your own explanation of Eliza’s disappearance?”

Thus encouraged, Annie fairly flowed into excited speech.

“White Slavers, sir, I’ve said so all along! Cook was always warning me against them. Don’t you sniff no scent, or eat any sweets—no matter how gentlemanly the fellow! Those were her words to me. And now they’ve got her! I’m sure of it. As likely as not, she’s been shipped to Turkey or one of them Eastern places where I’ve heard they like them fat!”

—“The Adventure of the Clapham Cook” (1923), Agatha Christie

“I see [said Wimsey]. And now you’re going to tell me Bertha Gotobed was got hold of by the White Slave people.”

How did you know?” asked Parker, a little peevishly.

“Because Scotland Yard have two maggots which crop up whenever anything happens to a young woman. Either it’s White Slavery or Dope Dens—sometimes both.”

—Unnatural Death (1927), by Dorothy L. Sayers

*

At 11: 00 a.m. on Sunday, July 18, 1920, seventeen-year-old Florence Lydia Rush, a clerical worker at the Blake and Knowles Steam Pump Works in East Cambridge, Massachusetts, left her home in the Eagle Hill neighborhood of East Boston, clad in a blue dress, pink scarf, hat, black stockings and brown pumps. She told her mother that she was devotedly going to church, but instead she strolled over to the nearby home of her fifteen-year-old chum (as the newspapers soon would term her), Gertrude Catherine Smith. After fluffy-haired Florence discarded her hat at Gertrude’s house, the pair set out together to spend the day at the resort of Revere Beach, located about four miles to the northeast at the city of Revere. Dubbed the “Coney Island of the East,” Revere Beach offered ample charms for Boston’s summer pleasure seekers, including such attractions as movie theaters, dance halls and roller coasters. Yet even more excitement appeared on the horizon, when, around 5:15 in the afternoon, after rain had just started to fall, Florence and Gertrude were approached by a car cruising down Revere Beach Parkway that was packed with six young men, who generously offered to give the girls a lift. Once the duo had crammed themselves into the crowded car, however, it was not long before some of the fellows, who claimed to come from the city of New Bedford, Massachusetts, became objectionably fresh. Florence and Gertrude were urged to ride with them to the neighborhood of Riverside in East Providence, Rhode Island, about sixty miles to the southwest, which was home to Crescent Park, another self-styled “Coney Island of the East.” As the machine headed toward the city of Chelsea, which was located about a mile from Eagle Hill, one of the young men rudely attempted to grab and kiss Gertrude, provoking the outraged girl to bite him on the arm and slap his face before leaping from the moving car, leaving five foot, one inch, 125-pound Florence behind, desperately screaming for help. The machine then sped off at a rapid clip toward Chelsea out of Gertrude’s sight, carrying away her friend Florence to a fate unknown, as sheets of rain started pouring down like tears.

This was the troubling tale that Gertrude Smith told after she finally made it back to her home at 345 Meridian Street in Eagle Hill, where she lived with her parents and sister. Once the news was carried to Florence’s recently widowed mother, Sarah, who resided just a few minutes’ walk from the Smiths at 62 West Eagle Street with her son Herbert, a twenty-year-old pipefitter at a soap factory, two other daughters and two grandchildren, the distraught woman hurried over to Police Station Seven, East Boston, where she frantically appealed to Captain James F. Hickey to retrieve her stolen child. By Tuesday, July 20 Boston newspapers were reporting that a vigorous search had commenced for a brazenly abducted Boston girl. That very evening Boston’s men in blue, accompanied by Herbert Rush, visited a hotel on Howard Street in Boston’s West End, where Florence was said to have registered under a fictitious name with another, older woman, who was previously familiar to the police as a suspected procuress. Determining that Florence and the older woman had left the hotel for the address of 18 Burgess Street in Providence, Rhode Island, Boston police wired their brethren in the Ocean State’s capital to be on the lookout for the pair, while Herbert and another male relative of Florence’s took a late train to Providence to be on the scene as well. Unfortunately, Providence police could locate neither hide nor hair of Florence. At the house at 18 Burgess Street, the domicile of sexagenarian widow Sue Sheldon and her widower cousin, they found two sixteen-year-old runaway girls from Haverhill, Massachusetts, Sophie Alartosky and Gertrude Sibulkin, who were taken into custody for their parents to retrieve. This was all well and good, but where in the world was Florence Rush?

The answer to this question came on the evening of Wednesday, July 21, when Florence herself walked into her chum Gertrude Smith’s house on Meridian Street, asking for the hat which she had left there on Sunday morning, when the church-dodging pair had fatefully set out together for their spot of fun at Revere Beach. Finding Florence “dazed” and unable coherently to answer their questions about her whereabouts of the last few days, the Smiths informed Florence’s aunt, Mary Jane Bloomer, a tow-boat captain’s wife who lived just across the street, of her lost niece’s return. Mrs. Bloomer promptly put Florence to bed at her house and summoned to the girl’s care J. Danforth Taylor, a bespectacled forty-four-year-old general practitioner who lived a few minutes’ walk to the south with his wife and daughter in a frame Italianate townhouse at 31 Princeton Street. Dr. Taylor pronounced Florence’s condition “serious” and speculated that the unfortunate girl was “suffering from drug poisoning, evidently administered in a liquid.” However, his physical examination of his patient revealed no marks of violence upon her body.

Despite her parlous state Florence was able to talk, albeit disjointedly. Asked how she had made it home, she replied, “I don’t know. A woman put me in an automobile and gave me a $1.50.” The Boston Globe speculated that this claim went well toward verifying what was becoming known as the “Providence white slaver theory,” as the cab fare from Providence to Boston tallied to $1.42. Florence also spoke suggestively of having been located somewhere near the water with a blonde woman who viciously pulled her hair, but that was all that could be gotten from her at the time. However, by the next day, Thursday, July 22, Florence was spilling hair-raising details about her recent ordeal, which gave the white slaver theory added life.

Dr. Taylor’s reviving patient told of having consumed in the car a piece of cake, which retrospectively she believed to have been poisoned. Her story follows, as divulged (and doubtlessly cleaned up) by the Boston Globe:

I made a feeble attempt to escape [from the car] but to no avail, and then I fell asleep and the next time I came to I was told that I was in Providence. It was still raining hard. I was terribly thirsty and asked for a drink and something to eat. I was given a glass of ginger ale. This burned my throat while I drank it, but I was so thirsty that I didn’t care. I remembered nothing else until I awoke again in a cottage with a screened piazza near the water.

There was a woman by the name of Alice there and a man by the name of Fred. The woman was a blonde and I would know her face out of a million. She hit me and pulled my hair and treated me roughly generally.

While lying there in a half dazed condition I heard three men in the next room. One of them said, “What are we going to do with the girl?” Another replied, “Put her with the rest of the chorus,” and the third said, “She’s too young.” Then one of them said in a gruff manner, “To h— with her, ship her to Cuba.”

Several hours passed and then the woman, Alice, took me to the Providence depot, gave me a ticket and ten cents and put me on a train for Boston. I don’t remember anything else about the ride other than seeing all the shops at Readville [a neighborhood in southern Boston].

Florence’s updated account differed from her earlier reported one, in that originally she had stated that the blonde woman (named Alice in the second account) had put her aboard a cab with $1.50 for the fare, while now she was saying that the mystery lady had given her a dime and boarded her on a train bound for Boston. “Miss Rush was unable to explain,” the Boston Globe now noted, how she had gotten over to Gertrude Smith’s house in the East End. However, this discrepancy in no way dissuaded the Globe from breathlessly reporting that Florence’s “story affirms the belief of the police that a gang of white slavers, with Providence as their headquarters, is operating in and about the amusement resorts in Boston and other parts of the state. Consequently young women are warned by the police not to accept invitations of chance acquaintances to an automobile ride” (as Florence and Gertrude had so naively done). The Globe drummed home the consequences of such careless action as the two girls had taken when it noted that Dr. Taylor, Florence’s attending physician, now stated “there was evidence that she had been criminally assaulted.” He also speculated that Florence’s captors had heavily dosed her with chloral, administered in some liquid form (i.e., not in cake).

Just three years earlier, in 1917, a purported white slavery outrage had shaken the nation. In New York City eighteen-year-old Ruth Cruger had gone missing in February, after having stopped at a motorcycle shop to have her ice skates sharpened. Incredibly, it took four months for the cellar of the motorcycle shop to be dug up, disinterring Ruth Cruger’s brutally slain body; and this was done not by New York City police, who had a cozy relationship with Alfredo Cocchi, the shop’s owner and the young woman’s murderer, but by a bold woman attorney and crime investigator named Grace Humiston, whom Ruth Cruger’s father had hired to find the truth about his daughter’s disappearance. During those four months of police inactivity, theories that white slavers had gotten their nasty hands on pretty young Ruth Cruger had proliferated in the press (spurred on by the crusading Grace Humiston), yet in the end they proved spurious. One sensation-seeking woman, who called herself Consuelo La Rue, claimed to be an Argentinian intrepidly investigating white slavery in the United States (though she was actually a certain Mrs. H. T. Clary from California). This imaginative person insisted that she possessed vital information about the Ruth Cruger case, but, although Grace Humiston embraced her farrago of fibs, it turned out that her “vital information” had been culled from Englishman Sax Rohmer’s hair-raising 1913 crime thriller, The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu. (On the Cruger case and Grace Humiston see Brad Ricca’s 2017 book Mrs. Sherlock Holmes: The True Story of New York’s Greatest Female Detective and the 1917 Missing Girl Case That Captivated a Nation.)

Concern over white slavery had arisen during the Progressive Era in the United States, as greater numbers of single young white women, sadly lacking in what was deemed proper adult supervision, entered big city workforces. In articles in McClure’s Magazine published in 1907 and 1909, muckraking journalist George Kibbe Turner frighteningly detailed a national network of white slavers in Boston, New York, New Orleans and Chicago which trafficked in likely young women for the price of fifty dollars a head. Numerous blood chilling exposés—so-called white slavery tracts or narratives—were published in the first two decades of the twentieth century, highlighting the danger of naïve unattached young ladies being spirited away from such seemingly innocuous but in reality perilous locales as ice cream parlors, fruit stands, movie theaters and amusement parks into seedy lives of prostitution by highly organized and ruthless criminal urban gangs, often of foreign origin (typically Italian, Greek, Jewish or Chinese). Purportedly factual works like Chicago clergyman Ernest Albert Bell’s Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls, Or, War on the White Slave Trade (1910) and Chicago prosecutor Clifford Griffith Roe’s The Great War on White Slavery, Or, Fighting for the Protection of Our Girls (1911) as well as Reginald Wright Kauffman’s bestselling novel The House of Bondage (1910), which was adapted for both film and stage in 1914, were indicative of the intense, if circumscribed, moral agitation of the time that prompted the federal government to pass the Mann Act (1910), which outlawed interstate or foreign traffic of women and girls “for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” Some congressmen expressed concern at the time about the vagueness of the words “any other immoral purpose,” but as Joseph Connor notes, “[m]oral outrage triumphed” over caution. A Tennessee representative who gloried in the unlikely cognomen of Thetus W. Sims expressed the ascendant view when he floridly insisted that the act must be passed without demur to prevent “the taking away by fraud or violence from doting mother or loving father, of some blue-eyed girl and immersing her in dens of infamy.” (See Joseph Connor’s 2020 Historynet article “The Mann Act: How a Law That Was Meant to Help Women Was Misused.”)

Unquestionably the sexual exploitation of women and girls was (and remains) a grave social problem, yet…the issue was irresponsibly sensationalized in the tracts and the press, almost invariably with pronounced racist and/or xenophobic implications.Unquestionably the sexual exploitation of women and girls was (and remains) a grave social problem, yet, as radical activist Emma Goldman noted, its dreary underpinnings of exploited family dysfunction and economic deprivation too often were ignored as the issue was irresponsibly sensationalized in the tracts and the press, almost invariably with pronounced racist and/or xenophobic implications. When in 1913 comely thirteen-year-old pencil factory worker Mary Phagan was strangled to death at her place of employment in Atlanta, Georgia, for example, her Jewish boss, Leo Frank, was arrested and convicted for the crime, authorities having been relentlessly urged on by a print media which wildly proclaimed Frank a sexually “depraved and degenerate Jew” and Phagan “the victim of a white slavery plot that was foiled only by her murder.” Two years later, after Frank’s death sentence had been courageously commuted by the Georgia governor, the unfortunate man, who long has been deemed guiltless of the girl’s brutal slaying by just about everyone outside of agenda-driven Aryans and white supremacists, was horrifically lynched by a mob of rabid avengers that had been incited to “get the Jew” by months of grotesque anti-Semitic rhetoric in newspapers and pamphlets.

As for the Mann Act, the imprecision of its wording quickly led, as its critics had feared, to selective prosecutions of consensual sex acts between men and women in the absence of commercial sex trafficking. Just three days after its passage, a New York grand jury concluded that, contrary to purple passages in press clippings and congressional speeches, there were no organizations “engaged as such in the traffic of women for immoral purposes.” Even George Kibbe Turner, who had been called to testify before the grand jury, admitted his writing had been “overstated and deceiving.” Yet predictably criminal prosecutors, who naturally were not averse to favorable press, found the vaguely worded act hard to resist. Boxer Jack Johnson, the first African-American heavyweight champion, was successively hauled into court for enticement under the Mann Act in 1912 and 1913 for travelling across state lines with younger white woman, with whom he had sex. The first prosecution collapsed when the nineteen-year-old woman, Lucille Cameron, who later married Johnson, refused to cooperate with the boxer’s zealous tormentors, but the government was able to convict Johnson the second time around, this time on the strength of testimony from his former girlfriend, twenty-three-year-old Belle Schreiber, a “manicure girl and burlesque queen.” Johnson, who was sentenced to a year in a federal penitentiary, fled the country with Lucille, nor returning to serve his sentence until 1920—coincidentally the year which saw the six weeks’ press wonder in Massachusetts over the Florence Rush affair.

While Florence, recovering under the solicitous ministrations of Dr. Taylor, had started to talk, her chum Gertrude, her own brain apparently unaddled, was actively assisting the police with their inquiries. Divulging that the randy young man who had attempted to molest her in the car had been addressed by his fellows as “Schmiddy,” Gertrude avowed that she could without hesitation identify him, as well as at least two of his buddies, if she saw them again. Her description of Schmiddy, which was said by the Boston Globe to be “vivid,” led to police in Chelsea apprehending as a person of interest a “well-known Chelsea Square habitué” and “resident of that city.” However, when Gertrude, accompanied by her father, went to Chelsea police headquarters on Friday, July 23, she proved unable to identify this man as the elusive Schmiddy and he was released.

The big break in the case came the next week, however, when two officers assigned to the investigation—Patrolman Bartholomew Winn of Station Seven and Captain William T. Tappan of Revere—received an anonymous letter postmarked at New Bedford which purported to identify the men in the car. On Thursday, July 29, the Boston Globe reported, the two officers traveled down to New Bedford, where they “interviewed one of the men who was in the machine, who admitted that the Rush girl had been taken to New Bedford.” Although he insisted that Gertrude had been politely allowed off the auto and that Florence had willingly accompanied him and his friends to New Bedford, Boston police announced that they were planning to secure a warrant for his arrest, as well as, quite possibly, warrants for his fellows.

On August 11 the Boston Globe announced that two New Bedford men, twenty-three year old Cornelius Vanderbilt Sweeney, a machinist at New Bedford’s Revere Copper Works (whose parents evidently were admirers of the great Victorian-era business tycoon), and twenty-eight-year-old Irving William Nelson, a former coxswain in the Coast Guard during the Great War and current New Bedford fireman, had been arraigned in Chelsea District Court that morning and charged with enticing Florence Rush to New Bedford, in what police dramatically declared “the worst [such case] ever called to their attention.” Both Florence and Gertrude testified at the arraignment, and their accounts of just what had happened to them after they left Revere Beach had undergone further revisions. Gertrude stuck to her story that she had had to fight her way out of the moving car, but in a startling turn she now allowed that “her chum went willingly with the men.” For her part, Florence conceded that she had never been imprisoned in Providence, contending now that the cottage where she had been held was located in New Bedford. Moreover, the accounts of Cornelius (or “Neil” as he was known) Sweeney and Irving Nelson, the self-admitted driver of the car, diverged greatly from Florence’s. The latter man declared flatly of Florence that, far from having been enticed by him and his buddies to New Bedford, “the girl could not be driven from the car and insisted on going with [them].” Additionally both Neil Sweeney—could he have been Gertrude’s “Schmiddy”?—and Irving Nelson testified that they knew nothing whatever about Florence having been “drugged while with them in New Bedford.” Both men pled not guilty to the charges and were committed to prison on bonds of $300 (about $4000 today).

After the dramatic testimony, provided on the morning of August 20, of “[p]retty 17-year-old Florence Rush” (as the Fall River Globe put it, newspapers evidently believing that “pretty” female victims of sex crimes made more compelling copy), Neil Sweeney was convicted of having enticed Florence for immoral purposes to the aptly named cottage “High Jinks,” located at Lakeside in the city of Westport, Massachusetts, about a dozen miles west of New Bedford. He was sentenced to a year in prison, while his more fortunate compatriot Irving Nelson was found not guilty and discharged. Sweeney appealed his sentence while being held under a bond of $1000 (about $13,000 today).

It went unremarked in the press that all the lurid talk from both police and Florence herself for the last several weeks of a Providence white slavery gang had blown away like billowing smoke in a draft. Concerning the depraved blonde adventuress named Alice, who was said to have slapped Florence’s face and pulled her hair, it seems more likely that she was merely a figment of the girl’s imagination, for by the time of the trial Alice evidently had disappeared, like Lewis Carroll’s fictional venturesome blonde protagonist, down the proverbial rabbit hole. When the polite euphemisms of the press and the law are stripped away, it would seem that instead of smashing a gang of nefarious white slavers, Boston police had successfully prosecuted a twenty-three-year-old man for having had sex with a seventeen-year-old girl. Had Florence actually been carried across the Massachusetts state line to Providence and interfered with there, Neil Sweeney could have been federally prosecuted under the Mann Act, but since she had never left the New Bedford area he was prosecuted for enticement at the state level. Yet why had Sweeney not been charged with sexual assault or rape? Had Florence been a nonconsensual sex partner, cruelly taken advantage of after having been administered a dose of chloral that rendered her unable to resist the advances of the five foot two-and-a-half inch Sweeney? (Florence’s account of poisoned cake—which might also have been indebted to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—surely can be set aside.) Or had she actually consented to sex with Sweeney? As far as I can adjudge, public opinion at the time of the trial seems clearly to have deemed Florence the innocent victim in the case, but soon the verdict on Florence, not to mention her fierce friend Gertrude, would dramatically shift, as new facts about their behavior came to light.

*

The headline of the Boston Globe article that was printed on Wednesday, August 25, just five days after the conviction of Neil Sweeney for enticement, blared: EAST BOSTON GIRLS ARE MISSING AGAIN. Like in the 1993 film Groundhog Day, it seemed that everything was repeating itself:

Two West Boston girls, Florence Rush…and Gertrude Smith…who only a short time ago figured in a kidnapping at the Revere Beach Parkway, are missing from home again. They have been gone since Sunday.

The parents of the missing girls are much wrought up over their continued absence and have asked the police to search for them.

When last seen the Smith girl wore a blue serge dress, bolero style, georgette waist, black satin hat and black shoes and stockings. The Rush girl wore a plaid dress and black shoes and stockings.

The report in the Boston Post was more detailed—and more damning. The Post asserted that the girls, who had told their parents that they were going to the movies, must have deliberately run away from their homes on Sunday evening, because Gertrude had taken two coats along with her. However, the fact that the duo supposedly had taken with them only the price of admission to the theater suggested that “they were in collusion with someone else in their flight.” The Post also noted that Florence’s action might result in a modification of the sentence imposed on Neil Sweeney, whose appeal was scheduled to be heard in September. Significantly, the Post used skeptical quotation marks when it referred to Florence’s prior “kidnapping.”

The unexpected culmination to Florence’s story came five days later on August 30, six weeks and a day after she had first vanished. On Friday the missing girl finally was traced, after an absence of five days’ duration, to the town of Kittery, Maine, which was located about seventy miles northeast of Eagle Hill. Florence claimed that she had been enticed away from home again by yet another artful young man, this time a designing fellow from Manchester, New Hampshire. (Where exactly chum Gertrude got off the thrill ride this time the newspapers did not divulge.) After spending the weekend unsuccessfully attempting to explain to her mother her latest misadventure with a tempting Adam, Florence was dragged into court by none other than Sarah Rush herself, who demanded that her daughter be prosecuted under the state’s so-called “Stubborn Child Law,” which had its inception in the seventeenth century and was not finally repealed until 1973. (Originally the literally puritanical law had allowed for the execution of unruly sons of at least sixteen years of age.) Florence pled guilty to the crime of stubbornness, but she begged the judge, Charles J. Brown, to give her one last chance to reform on her own. Judge Brown sentenced the miscreant to a year at the historic Lancaster Industrial School for Girls, the country’s first female reform school, but he suspended execution of this sentence, provided that Florence immediately left Boston. At the conclusion of the proceeding the teenager thereby departed the city to board with relatives in another part of the state. Having been deemed an incorrigible and out-of-control child, Florence essentially had been “warned out” of Boston (another old Puritan practice), the people of the city, as represented by their duly authorized legal authorities, seemingly having decided to wash their hands of the teenager and her news catching ways.

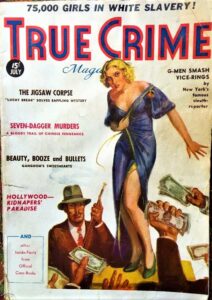

For many years after Florence Rush’s fervid phantom encounter with fictive Providence white slavers, similarly lurid accounts of pretty young white girls inveigled into horrid lives of sexual servitude appeared not only in newspapers but in both the crime fiction and true crime accounts which became so popular during the Twenties through the Fifties, in detective and thriller novels and pulp magazines and digests. True crime accounts in the pulps piously pretended that they were doing their part to expose actual social problems afflicting America when in truth their goal, surely, was to exploit these problems commercially by sexually titillating their readers for profit. “75,000 GIRLS IN WHITE SLAVERY!” shrieked True Crime Magazine on the cover of its July 1936 issue, which showed men bidding on an attractive, cowering blonde captive. For only fifteen cents purchasers of this number could read rousing, if not arousing, accounts of heroic, hard-fisted G-Men smashing vice rings and of “Hollywood—Kidnapper’s Paradise.” The magazine Exposed promised even more in the way of criminal sexual revelations in its September 1942 “Smashing the White Slave Mart!” issue, which on its cover featured a scantily clad blonde in chains (and red high heels): “Girls in Bondage—Uncensored! Sensational! True!” By this time other true crime magazines had patriotically put the white slavery menace to use in vilifying America’s Axis enemies, with the July 1942 issue of Tru-Life Detective Cases, for example, featuring an Asian man menacing a prone distraught blonde white woman beneath the eye-catching headline: VIRGIN in the DEVIL’S DEN: “I Was Sold To JAPANESE WHITE SLAVERS.” Clearly there was a bull market in blondes, at least on the covers of pulp crime mags. (Conversely, the ghastly tragedy of the thousands of real life Asian women—euphemistically termed “comfort women”—who had been sexually enslaved by the Imperial Japanese Army seemingly did not interest the pulps.)

In the field of crime fiction probably no author made greater use of the wretched white slavery motif than Sax Rohmer in his long-running series of Dr. Fu-Manchu “yellow peril” thrillers (the first of which, as we have seen, had inflamed the mind of Consuelo La Rue). Although during the Twenties Crime Queens Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers mocked the subject of white slavery in their detective fiction as a bugbear of dim maidservants and police detectives (see the quotations at the head of this article), other, far more solemn crime writers referenced it dead seriously in their writing. For example, in The Black Gang, a 1922 thriller by popular English writer Sapper (H. C. McNeile), the author’s hit-first-ask-questions-later series hero, Captain Hugh “Bulldog” Drummond, confronts an insidious coterie of foreign knaves and villains (including two Jews, “flashily dressed” and “addicted to cheap jewellery”),who, in addition to attempting generally to destroy life in England as we know it, dabble in “White Slave Traffic of the worst type….They generally drug the girls with cocaine or some dope first.” Additionally, pretty young white women mysteriously vanish in Anglo-Irish detective novelist Freeman Wills Crofts’ 1929 mystery The Box Office Murders, which features as well an Amazonian blonde accomplice of a dastardly criminal gang suggestively named Gwen Lestrange, who harshly mistreats plucky captive heroine Molly Moran.

Another 1929 detective novel, Nemesis at Raynham Parva, by Scottish chemist and mystery writer J. J. Connington (aka Alfred Walter Stewart), is particularly interesting in this regard, in that its subject matter was actually suggested to the author by his prominent Jewish publisher, Victor Gollancz, in light of the League of Nations’ 1927 reports on white slavery and the publication in 1928 of The Road to Buenos Ayres, a much lauded account of prostitution in Argentina by pioneering French investigative journalist Albert Londres. In the Connington mystery a trio of nice but dangerously naïve young English women is menaced by a dastardly Argentine slaver—or “dago” in the chauvinistic parlance of the novel. “Spaniards aren’t necessarily dagoes, you know, Anne. Some of them are sound stuff,” judiciously allows series detective Sir Clinton Driffield of an Argentinian named Francia, before the archfiend’s anodyne cover is blown, although even then Sir Clinton significantly adds: “I admit I’d have been better pleased if Elsie had kept to her own people and left foreigners alone.” The author himself later admitted: “Personally, I think the white slavery book is rather a poor one.”

With their lurid melodrama and invariably racist and ethnophobic sentiments, white slavery mysteries generally did make rather poor examples of the crime fiction form (in his rules for writing detective fiction, Father Ronald Knox did not ban “Chinamen” for nothing), yet they kept appearing nonetheless. The execrable though once popular English thriller author Sydney Horler, for example, contributed his stab at white slavery fiction in 1953 with the novel The Cage, which details the efforts of a despicable troupe of Romanians to ensnare ingenuous small-town Englishwomen, including unsubtly named heroine Virginia Hoyle (i.e., “virgin hole”), for the delectation of depraved clients in East Asia. The next year ostensibly serious authors A. W. Pezet and Bradford Chambers published a book called Greatest Crimes of the Century, which included a chapter, “The White Slave Scandals,” in which they credulously reported that during the earlier decades of the century the United States had been afflicted with an epidemic of white slavery, during which thousands of “attractive, clean, well-bred girls were being lured and trapped into lives of shame and degradation as white slaves; prostitutes for the libertines of Latin America, and also in a few instances ‘wives’ for jungle chiefs in Africa and concubines for the harems of the Orient.” (Surprisingly, Bradford Chambers, co-author of this inept book, went on to become director of the Council on Interracial Books for Children, which developed guidelines for determining whether youth-oriented textbooks and storybooks were racist.)

While as far as we know there had been no African “jungle chiefs”—even imaginary ones—involved in Florence Rush’s summer escapades, in Providence the infamous Morelli crime family had become dangerously active by 1920, with some even suspecting the Morelli brothers of having masterminded the armed robbery and murders committed that year at Braintree, Massachusetts, for which Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were convicted and finally executed after years of controversy. So perhaps it is no wonder that Bostonians looked to the Rhode Island capital’s dens of vice for the solution of the Florence Rush enigma. Ultimately, however, the answers to all of the riddles in the case likely remained locked away in Florence Rush’s head. Possibly the whole scandal in which she became embroiled with Neil Sweeney in the summer of 1920 arose out of an understandable reluctance on her part to admit publicly that she had had sex with a young man. If this is indeed the case, then Florence, inspired by intense and insistent questioning about Providence white slavers, fabricated an elaborately embroidered tale, the likes of which might not have been seen in New England since the Salem witch trials.

Fairly or not, this seems to have become Boston’s view of the matter by the time Florence was condemned as a stubborn child and warned out of the city. Over seven years later Edmund Lester Pearson, a genteel American true crime writer and native of Newburyport, Massachusetts, in his 1928 Vanity Fair article “Some Accomplished Female Liars,” might have had not only Christian evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson in mind but Florence Rush as well (along with others like her), when he wrote waspishly of the “Canning sisterhood” (so named after the briefly missing eighteenth-century English servant girl Elizabeth Canning) that they “have a definite object for lying. It is not art for its own sake with them; they have need to account for their mysterious absences. If they are inventive enough, if they can be carried into Mexico and be forced to walk for miles over the hot sands, they may even become romantic heroines.” (Aimee Semple McPherson had vanished two years earlier in May 1926, reappearing five weeks later in Mexico; her disappearance was followed seven months later in England by that of Agatha Christie.) Ignored in all the righteous condemnation of Florence’s bad behavior, however, was the decisive role which, for purposes of their own, both police and press (not to mention frantic relatives and the ever helpful Dr. Danforth Taylor) might have played in implanting the white slavery narrative in an immature and impressionable adolescent mind.

In April 1921, less than a year after Florence Rush’s original disappearance, the Boston Post, in what could almost be seen as a minor act of press penance, ran a short article on how Dr. Heinrich Kopp, Kriminal Kommissar for sex offenses in the Berlin police department, had thrown cold water on heated white slavery fancies, bluntly dismissing as “myth” the plethora of lurid media stories from the last two decades “telling of the exportation of girls to foreign countries, where they became the property of white slavers.” That same year, Florence Rush, now all of eighteen years old, wed John Anthony King, a taxi driver six months younger than she who ironically had been born in that infamous nest of vipers, Providence. When she gave birth the next year to the couple’s first child, a son named John Anthony King, Jr., she was safely ensconced again in East Boston with her lawful wedded husband. Eight years later, in the 1930 census, the Kings, whose rapidly growing family now included seven children, resided at 131 East Putman Street, about a ten minutes’ walk to the southeast of Sarah Rush’s house on West Eagle Street. After Florence King died in East Boston in 1978, she left behind no fewer than eleven children (one of her sons having predeceased her). Perhaps her impressive record of procreative sexual fecundity, legitimated by the holy state of matrimony, had redeemed her in the eyes of her neighbors.

Conversely the matrimonial state seems to have eluded Gertrude Smith (or perhaps it might be more accurate to state that Gertrude eluded the matrimonial state). In 1940 Florence’s former adolescent sidekick, now thirty-five and single, was employed as a hairdresser and resided some five miles southwest of Eagle Hill at attractive lodgings for single women at 182 Beacon Street in Boston’s Back Bay. As for those rambunctious New Bedford boys, Neil Sweeney and his friend Irving Nelson, the latter man passed away in New Bedford in 1956 at the age of sixty-four, having been once married but apparently childless, while Sweeney, retired from his longtime position as janitor at the New Bedford post office, died in Tampa, Florida in 1970 at the age of seventy-three, leaving behind a wife and a single child, a daughter named Pearl, whose name oddly echoes that of the symbolical child Pearl in Nathaniel’s Hawthorne’s classic New England novel The Scarlet Letter, who in her person symbolizes the shame of the coital sin of her parents, Hester Prynne and Arthur Dimmesdale. Whether Neil Sweeney actually served a term in prison for his crime of sexual congress with Florence Rush I have been unable to determine. Many men, some of them vastly more prominent than he, later fell into the capacious net of the Mann Act, including architect Frank Lloyd Wright and actor Charlie Chaplin, both of whom were arrested under the “immoral purpose” language of the act (in 1924 and 1942 respectively), on account of their having crossed state lines with younger women in their twenties, with whom they allegedly had enjoyed consensual sexual relations.

And what of that minor player in the Florence Rush white slavery drama, Dr. J. Danforth Taylor, who opined, according to press accounts, that Florence had been dosed with chloral and sexually molested? A rather interesting local character was the good doctor. Just over two years to the day before Florence first vanished, Dr. Taylor, a prominent rationalist and contributor to the The Truth Seeker (a journal modestly devoted to “science, morals, free thought, free discussions, liberalism, sexual equality, labor reform, progression, free education, and whatever tends to elevate and emancipate the human race), had called the Boston Globe from his summer cottage on Nauset Beach, outside the town of Orleans in Cape Cod, to alert the United States to the fact that the country was currently under attack by a German U-Boat, which had just sunk a tug and four barges off the coast and was now sending shells, frighteningly if harmlessly, scudding into the beach. The Boston Globe was duly grateful for this tremendous scoop, sending the doctor a check for $150 (about $2000 today) and a box of expensive cigars. No smoker himself, the abstemious Dr. Taylor distributed the cigars to local men who had helped rescue wounded sailors offshore. One old codger of a Cape Codder puffed one of the cigars for a few seconds before drawling, “Pretty good cigar, Doc, but I like my 2-for-5 stogies better.”

Dr. Taylor’s nine-year-old daughter, Phoebe, had been present at the Taylor cottage the day Germany launched its sole attack on American soil during the Great War. Before she was herded down with the other children to the safety of the cellar, young Phoebe boldly managed to snatch a glimpse of the German submarine’s conning tower through a pair of binoculars. Doubtlessly she was around the house in Boston two years later during the Florence Rush imbroglio, trying to grab what fragments of scandalized gossip that she could. Dr. Taylor had hoped that the baby who proved his only child would be a boy, but resignedly he sent his intrepid daughter to Barnard College, an elite women’s liberal arts school in New York City, from which she graduated in 1930. After proving by her own sardonic admission an almost immediate flop in the business world, Phoebe at the age of twenty-one decided to write a detective novel, which she entitled The Cape Cod Mystery. Upon the novel’s publication in 1931, a charmed world was introduced to Phoebe’s astute homespun amateur detective Asey Mayo, the “Codfish Sherlock,” and thus was launched one of the most successful mystery series of the twentieth century. (Later on, there was also another successful series, which Phoebe published under the pseudonym Alice Tilton.) Perhaps Asey’s sometime Watson, voluble Doc Cummings, owed inspiration to the author’s own opinionated father. Moreover, in her many zestful, oddball tales of murder and felonious mayhem in Massachusetts, Phoebe Atwood Taylor occasionally references both white slavery and German submarines, evincing a fertile imagination which arguably rivals that of that impulsive, wayward girl who was the author’s elder by just seven years, Florence Lydia Rush.