Picture a detective. I bet you’re imagining a haggard drunk sprawled across a Murphy bed, suit rumpled, wallet empty, address book full of clients who won’t pay and exes who hate their guts. Or maybe they’re a high-strung genius—think Nero Wolfe, Hercule Poirot, or Sherlock Holmes—whose brilliance has made it impossible to connect with other people. Either way, they probably don’t date. Your average detective, whether amateur or professional, tends to be tortured, isolated, and misanthropic—traits intended to represent toughness but which are actually just depressing. For these sleuths, total romantic failure—often blamed on a shrewish spouse’s jealousy of the detective’s work—is presented as martyrdom. It’s a cliché that often slides into sexism and I think our detectives deserve better.

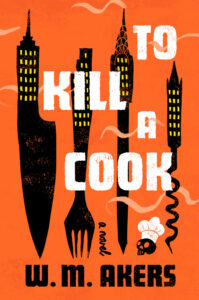

Across literature and television, only a handful of well-known detectives have what it takes to maintain a stable romantic relationship. As an author, I get it. My detectives, from the Westside novels to my freshly released 1970s food world mystery To Kill a Cook, tend to be too prickly and independent for long term coupling. Like most writers, I’m reluctant to let my heroes be happy, since in fiction being happy is dangerously close to being dull. But in the right hands, a long-term relationship can humanize a detective and still offer plenty of conflict. So as we stare down the barrel of Valentine’s Day, I’d like to celebrate a few detectives and their spouses who don’t let murder get in the way of love—even if their relationships aren’t always the healthiest. We’ll go from most romantic to least, starting with…

The Barnabys and Their Wives

In the decades-spanning British procedural Midsomer Murders, the home lives of the two lead detectives—first Tom Barnaby (John Nettles) and then his cousin John (Neil Dudgeon)—offer a relief from the grisly murders that drive the show. Wives Joyce (Jane Wymark) and Sarah (Fiona Dolman) are fully realized characters, with careers and hobbies and lives outside their husbands. They provide gentle domestic conflict—teasing their husbands about home repairs, say—and the occasional brilliant observation that helps solve a case.

Despite ordinary marital friction, Joyce and Sarah seem happy with their lives in Britain’s most murderous county. While a cliché cop’s wife is forever haranguing him to retire, these two prefer having their men out of the house. In series 12’s “Secrets and Spies,” when Tom Barnaby resigns in protest of official interference in a case, Joyce is horrified.

“Now we can do all those things we said we’d do when I retired,” he announces proudly.

“Like what?” she says.

“Erm, oh, you know…er…retirement things. Cruises. Whatever.”

Giving him a look like he’s just pronounced a death sentence, she moans, “Oh, God!”

Thankfully for both of them, he soon gets back to work.

Inspector and Madame Maigret

The terror of the Paris underworld, Georges Simenon’s Maigret—played brilliantly on screen by Michael Gambon—exists in a world of shadows and fog. He spends as much time chasing comfort as he does killers—he’s always huddling up to a stove, sneaking a quick beer, or savoring a pipe. His home on the Boulevard Richard-Lenoir, which he shares with the seldom seem Madame Maigret, represents a domestic idyll that he too rarely gets to enjoy.

In Félicie, translated in English as Maigret and the Toy Village, Maigret is in the middle of a hellish stretch of all-nighters when his wife sends him a note saying that her sister has brought freshly picked wild mushrooms, cèpes, for dinner, adding, “I do hope you’ll be able to join us.” Maigret can’t make it, and spends the rest of the evening dreaming, “of the cèpes, simmering on the stove, and exuding an appetizing smell of garlic and damp woodland.” Madame Maigret is no pushover—when she thinks her husband has a crush on a flirtatious young suspect, she mocks him for it—but their relationship is mature enough that she doesn’t blame him when the telephone rings with news of another murder, even if she “always longed to stifle it with a pillow, as if it were some malevolent living thing.”

Mary Beth and Harvey Lacey

The emotional core of Cagney & Lacey, the underrated 1980s police procedural, was the relationship between NYPD detective Mary Beth Lacey (Tyne Daly) and her husband Harvey (John Karlen), a former construction worker whose career was derailed by vertigo. Gruff, grumpy, and affectionate, Harv gives Mary Beth the same unconditional support expected of fictional detectives’ wives. Their relationship is warm, adult, and often quite horny, generating the kinds of low-key subplots that, like in Midsomer Murders, balance out the murders.

But occasionally, Harv gets into the action. In the second season episode “High Steel,” Mary Beth and Harv sneak onto a construction site in search of evidence that a developer is cutting corners on materials. As Harv examines a rivet— “Quality work cannot be rushed,” he says—the crooked foreman gets the drop on them, forcing them at gunpoint to the top of the half-finished building. Mary Beth ends up dangling from a girder and Harv has to overcome his vertigo to make his way out to her. Paralyzed by fear, she’s unable to loosen her grip, so Harv punches her in the jaw, knocking her unconscious so he can drag her back to safety.

If the image of Harv heroically punching his wife in the face leaves a sour taste in your mouth, I apologize, because it gets weirder from here.

Nick & Nora Charles

Made famous on screen by William Powell and Myrna Loy, Dashiell Hammett’s wise-cracking, highball-swilling heroes were introduced in 1933’s The Thin Man, a sparkling mystery that’s equally comic and hard-boiled. Nick is a former PI who retired to manage the fortune of his much younger wife—as he tells her, “I haven’t the time [for work]: I’m too busy trying to see that you don’t lose any of the money I married you for.” Their banter is impeccable and their relationship is sweet, as long as, like Nick and Nora, you don’t think too hard about how much they drink.

While these two may not be great for each other, they have a good time. “A woman with hair on her chest,” Nora’s not skittish about murder—in fact, she’s too eager to get involved. When a tough named Morelli barges into their hotel room and holds them at gunpoint, Nora is “excited, but apparently not frightened: she may have been watching a horse she had a bet on coming down the stretch with a nose lead.” To save his wife, Nick follows the same instincts that guided Harv Lacey:

“I hit Nora with my left hand, knocking her down across the room. The pillow I chucked with my right hand at Morelli’s gun seemed to have no weight; it drifted slow as a piece of tissue paper. No noise in the world, before or after, was ever as loud as Morelli’s gun going off.”

The bullet glances off Nick’s chest; the gunman is caught. When she comes to, Nora is annoyed that she missed the action.

Lieutenant and Mrs. Columbo

And so we turn from a pair of codependent alcoholics to the most famous unseen character in the history of American TV. Although he mentions his wife frequently, Lt. Columbo (Peter Falk) always has some excuse as to why she can’t appear. She’s bowling, say, or shopping for fish, or ordering a pedicure for their basset hound, Dog. Her conspicuous absence has inspired theories that Mrs. Columbo doesn’t exist, but is instead either a rhetorical device to disarm suspects or a figment of Columbo’s imagination. (The internet’s most dedicated fans mostly agree that she does exist—but that the Kate Mulgrew show doesn’t count.)

If Columbo’s stories about his wife are true, they seem to be a happy couple. Their most pointed disagreement comes in “Now You See Him,” when his wife replaces the detective’s iconic raincoat with a newer model, which Columbo finds so uncomfortable that he rips it off and tosses it aside, declaring, “I can’t think in this coat!” He spends the rest of the episode trying to get it stolen and finally convinces his wife to “change it for something new.”

So those are some of the most successful romantic relationships in the mystery canon—and the list features a woman who might be imaginary and two men who respond to danger by slugging their wives in the jaw. We can do better, folks! In the coming years I’d like to see more detectives—queer and straight, cis and trans, monogamous and otherwise—who aren’t afraid of romance. A functional relationship offers plenty of conflict—and there’s nothing wrong with letting our detectives be happy once in a while, too.

***