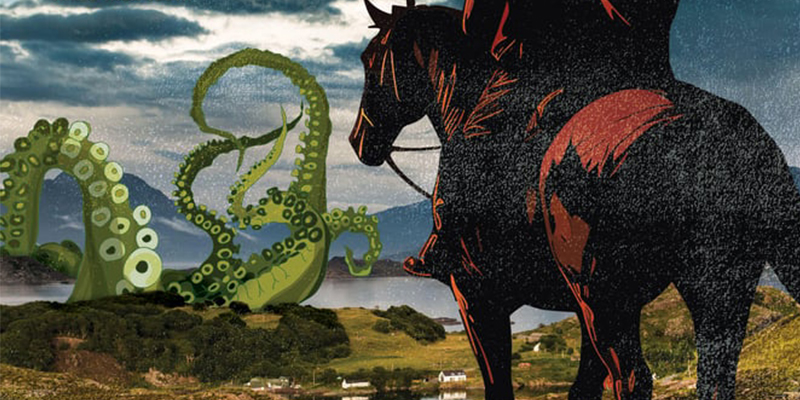

The weird western is nothing new. Since at least 1932, with Robert E. Howard’s “The Horror from the Mound,” writers have been combining fantasy, science-fiction, and horror with the Old West in novels, stories, comics, and films. The genre built to a crescendo in the 1980s. The last major iteration I can remember is the 2011 movie Cowboys & Aliens. In our time, well into the 21st century, the genre and the term “weird west” feel long out of fashion—though, like the western itself, it’s a fire that never completely goes out. It flares up again in such tales as the recent limited streaming series Outer Range. My agent wisely describes my new novel as “historical fantasy.”

Actually, that is a more accurate term for it. It’s set in the American West of the 1880s, and while unquestionably “weird,” it combines multiple, quite different kinds of story in the way that the vastly-ranging and diverse genre of fantasy does. Some years ago, I heard the horror and fantasy author Peter Straub say, “We read and write fantasy because it’s the genre most capable of depicting the world as it really is.” I’d like to believe that The Country Under Heaven is much more than just “weird” and “a western.”

How can a novel encompass fantasy, horror, science-fiction, romance, the ghost story, literary fiction, and the western? And perhaps more importantly, why would a book try to do that? What was the author thinking? The simplest answer—and certainly a true one—is, “That’s the world I live in.” I would argue it’s the world we all live in, whether we know it or not. We are steeped in the human journey—in tragedy, comedy, pathos, memory, horror, change, mortality. This is the life we live. We rub elbows with ghosts. Life breaks our hearts, then leaves us breathless in the face of beauty. It is supernatural.

Since early childhood, I’ve loved stories of the Old West . . . and along with them, stories of monsters. The original King Kong changed me forever—an island not on any map? A colossal wall with a giant gate, and people who live in terror of what’s behind it? And . . . dinosaurs? A gargantuan gorilla?! I’m in! Whereas many kids grow up hearing sports stories from their dads, I heard about cowboys, life on the trail, with coyotes howling over lonesome canyons under the desert moon. My dad also told me all about cryptozoology—Bigfoot, the Mothman, the Loch Ness Monster . . . and UFOs, ancient mysteries, rains of frogs . . . I simply could not get enough of such things.

But those notions aren’t just childish escapism. There’s a more serious side to both. Monsters in our imaginative stories give us something we can externalize and fight against—escape from or even defeat—as we deal with the real-life horrors of loss, illness, violence, human cruelty, injustice, death. We’ve been at it for as long as we’ve had a language: our oldest story first recorded in any form of English is Beowulf, written down sometime around 1,000 C.E., and likely existing in oral form a good while before that. It’s a monster story. That we study now in college literature classes.

And the western. Beyond the trappings and tropes, there’s a real poignance, a pathos to the Old West. It wasn’t a long period, and it was all about rapid change. Native Americans were being forced off the lands they’d known for generations. Rails were laid, telegraph lines strung, the buffalo were being slaughtered. White people were flocking westward after minerals, occupying the land, putting up fences where fences had never been a thing. Life was harsh. There weren’t many old people, and almost no one had a Hollywood smile. Westerns are mostly elegies—sad, beautiful songs about endings. Things were vanishing that would not come again . . . and it was all happening in a dramatic and beautiful setting—a lovely land that could kill you in the blink of an eye. Where there’s very little law, personal actions make a tremendous difference. Evil gets really ugly fast. Integrity and kindness are more precious than ever. So these big, epic, stirring human stories practically tell themselves . . . and now we’re into literary fiction. “Welcome, pardner, to the Literary Territory.”

One important truth I’ve learned about writing is that I always have to ask myself on at least two levels, “What is this story about?” For example, without giving spoilers, in my novel’s chapter about Hat Toynbee in Montana, the surface answer is that the main character, Ovid Vesper, has to accompany Hat Toynbee on a dangerous journey up into the Rocky Mountains to do a particular thing. But the chapter is really about something else—hence, the chapter’s title, “The Good Hour.” At such moments, good genre work becomes literary, when it uncovers truths about what it means to be human.

The Country Under Heaven has fantasy threads, too—particularly elements of folk and fairy tales. In the chapter “Wind,” the character Windwagon Smith is straight out of American folklore; he’s a figure something like Paul Bunyan, and he may have been based on one or more real people. He fit right into my purposes, and I wove him in, because I think such elements give readers a sense, maybe a subconscious one, of I’ve heard this somewhere before; this is familiar. It rings true. There’s a similar thing going on in the chapter “The Sound of Bells”—again, without giving too much away, in accounts of medieval history, there are reports attested to be historical fact of two children very much like these children. Richard Decalne and the place called Woolpit are borrowed from the medieval record. In this part of the novel, passage between worlds figures large. I’ve always loved tales of Faery, which tend to be about borders and passages, about seasons and times of day when the walls between worlds grow thin. We don’t have a fairy-lore in the U.S.—we’re too young a country. But I grew up in Illinois, among the cornfields. To enter a cornfield is to plunge into a shadowy, whispering, emerald world that only exists in the summertime. Gone by the later fall, it’s a hidden, secret, ephemeral world . . . so maybe we Americans do have some inklings of Faery after all.

There’s also an element of science-fiction in Ovid’s story, mainly in the otherworldly “Craither” that follows Ovid relentlessly through the book. I’m not sure the Craither is supernatural. It might be . . . or it might, like the bizarre creature in Ambrose Bierce’s “The Damned Thing,” just be something . . . different. It might be inexplicable simply because it’s so far beyond our experience.

Whatever else it is, The Country Under Heaven has been a new kind of storytelling for me. It’s the first time a story or novel has first contacted me not through a place but through a voice: a main character’s steady, gentle, confident voice, speaking to me with a story to tell.

***