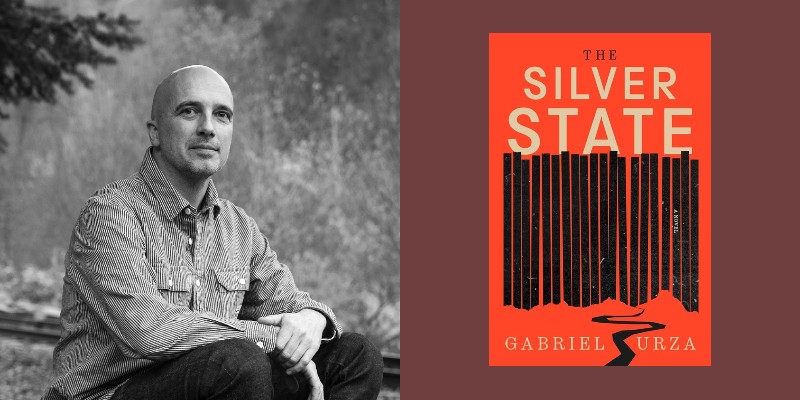

Gabriel Urza’s new novel The Silver State is a legal thriller that is first and foremost about the experience of a being a public defender. Urza himself was one for many years in Reno, Nevada, where the book is set. Centering on one death penalty case that the book’s main character Santi tried and lost early in his career– which isn’t spoiling anything, as it’s revealed in the first few pages. The book’s tension comes from uncovering what caused the case to unravel, which is tied closely to the nature of the system and what it means to be a public defender. Meeting Santi ten years later as he receives a letter from his former client, now awaiting an execution date, we learn about how the idealistic young lawyer burned out and are forced to confront the nature of a system where not only is “justice” not possible, it’s never the point. It is a precisely structured novel that is haunting and powerful to the end. Urza currently lives in Oregon where he teaches at Portland State University and we spoke recently about the novel, how his experiences informed the book and the city of Reno.

To start, could you talk a little just about where the idea for the book began and what was the initial kernel?

I was a public defender for about five years in Reno and then I burned out. The book and the storyline are totally fictional, but the impulse to write a book about a young public defender was me trying to make sense of my experience as a public defender. The characters and the storyline themselves, they are really set in Nevada in terms of a sense of place. And Reno in particular. Reno as a smaller gambling town, especially in the earlier sections of the book, it’s kind of a unique place. I hoped to capture some of that.

I was also thinking a lot about the iniquities that we see in the law and how they actually come to be in the courtroom. For example, one of the things that I certainly knew going into my job was about disparities in race, in gender, in how those play out as related to what crimes are prosecuted and what crimes aren’t. The identities of the accused, the identities of the alleged victims, and how much that all plays in. But I didn’t know where those iniquities happen mechanically in the process. In these characters, I was exploring some of that those ideas about how that happens in practice.

So many legal thrillers are about how can we use the law to achieve some sense of fairness, some sense of justice, to set things right. For a lawyer, whether the defender or prosecutor, or anyone in the system, really– the bailiff, the judge– that’s never the question any of them are asking. Their job is something else.

Absolutely. I think about that from an attorney’s standpoint, because your job is really to be an advocate and to advocate as hard as you possibly can for your clients. I think this is in some ways a problem of our system. Because it’s so adversarial, we think of our jobs as advocating and fighting as hard as possible, and leaving it to other parts of the system to figure out what’s right and what’s wrong. That makes sense on paper, but I think in practice, it often leads to bad outcomes. Because if you have a prosecutor that sees their job as only to convict, or I think it’s different, but if a defense attorney sees their job is only to acquit, you get some weird practices. You get some weird outcomes. You’re always waiting for somebody else to be the backstop.

The other strange thing about being a public defender, and I hope that Santi captures this in the book, is that you are dealing with a huge volume of cases. The sense of justice that you have tends to be more cumulative. Because if you advocate as hard as you can for one client, that might really adversely affect another client the next time you see that same judge or district attorney in the courtroom. There’s a real tension there in terms of how much we should advocate and who we advocate for.

While the book is about a death penalty case, Santi also has all these smaller cases. And for those individuals, this is their life. The outcome could completely affect everything in their lives.

Absolutely.

Especially when it’s a bullshit charge. And Santi can’t necessarily spend the time and energy to push against the bullshit.

Exactly. And I think “bullshit” is a perfect description, because there are so many of these cases that just need attention and resources. The volume that public defenders face, I think, is the biggest impediment towards them doing their job the best they can. As a practicing attorney, we can become inured to the idea that a small case is the biggest event in a person’s life. A small misdemeanor drug charge, for example, can change somebody’s life forever in terms of whether you get out of jail, whether you have to go to prison, whether you are on probation for the next two years, whether you can get a job, whether it affects you keeping custody of your kids. All these snowballing effects of what a lot of people consider a small crime are easy to forget, but they’re very real.

You don’t really get into the policing aspect, and we’ve been talking about racial profiling and quotas and unfairness, you’re looking at prosecutors and judges and what happens when you have a big case, when they’re in a bad mood, when they’re pissed off at you for some other reason, and take it out on another client.

I read recently that when you get sentenced relative to the last time the judge has eaten has a huge outcome on your sentence. If you think about these arbitrary elements, these very human elements that change people’s lives, it’s really unsettling. I think we see people in a courtroom, and they’re in suits, and they have degrees, and it gives a feeling of order and a process. But it’s such a human process. I think people don’t understand that.

Talk a little about the structure, because you clearly spent a lot of time trying to figure out just how to structure and frame the book.

I’m so glad you asked that. I did think a lot about it. I thought about Santi as an attorney. At the time he’s telling this story, he’s been an attorney for ten years. I think that he goes to the process of the judicial system as a way to make order of chaotic things. And so when his life is upturned by this news– he gets this letter from a former client that’s on death row– the only way that he can make sense of it is to think about his own sense of responsibility and complicity in these events. As both an attorney and as somebody who’s being accused.

The novel takes the shape of a trial. [Santi] is thinking about the evidence against him that a prosecutor would present. He’s thinking about the evidence that he would put forth on his own behalf to suggest that even if the things that he was accused of happened, there might be a reason why they happened. That there’s mitigation evidence there that somebody might understand. Ultimately the story asks the reader to step in as a decider. Hopefully that puts a reader in a place where they get to have some agency over the story and the meaning-making behind the story.

I don’t want to spoil the book, but we’re introduced to Santi ten years after these events. He’s burned out or right on the edge. This case represents failure. For him, this is the case where an innocent man was sent away. He knows that it’s not the only time that happened, but it represents failure.

I think it does represent the failure that is kind of unavoidable for him as a public defender. It’s coinciding with other things that are happening in his life. He’s married now. He has a daughter. I think his sense of danger, his sense of guilt and complicity, is running head-on with a sense of vulnerability that’s coming from his place in life. He has a life that is not perfect, but it’s one that I think that he really loves. To have these ideas from his past coming back and haunting him, they really put him in a place where everything he’s thought feels unstable. About his value as an attorney. About the value of the profession. About what it means to be both a victim and a perpetrator in the system in some ways.

It’s not just his personal failure as an attorney. It’s not what he sees as a systemic failure. That an innocent person could be convicted or go to jail. He’s accepted that this isn’t a failing of the system. This is part of the system.

That’s it. Exactly. I think he is realizing that you cannot be a moral actor in an immoral system. That, I think, is a real hard realization to come to when you’ve dedicated so much of your life, not just to learning that trade, but to believing in that system. I think, like me, Santi probably is a bit of an idealist coming into the job. He is somebody who probably read To Kill a Mockingbird in high school and thought that Atticus Fitch was a great attorney. I think when you live the experience and then go back to that book, you realize that the victims in that book don’t really make it to the page as much as they should. And that it’s not really about Atticus. I think Santi is probably there to some degree, by the end of the book. I think he feels like he doesn’t see a way forward.

The book kind of ends in this place where he understands his role now in the system is at best, to mitigate harm. Not to solve anything or save anyone. Which kind of zaps the idealism out of you a little.

Yeah. Although when you put it that way, mitigating harm is a good thing, right? I’m not sure if you’re familiar with this idea of moral harm or moral injury.

A little.

It’s come into mode in the last few years. It’s hinting at this idea of the specific sort of psychological damage that happens when you are doing something that you think is a moral activity, and it ends up causing harm in the process. You see this in reference to people in the military, people even in medicine, when they have to make decisions about who gets saved and who doesn’t. Things like that. There’s a sense in which you can make all the right decisions and still cause harm. And you have to cause harm. I think that that’s a tough realization to come to.

In the past, his girlfriend works in an ER, where her job has this similar sense of triage and failure.

Absolutely.

Which she seems to understand, but in those early scenes, he’s still an idealist who doesn’t see his job in that way.

I think he’s also incapable of processing in the way that she wants to. She understands what’s happening as much as he does, but he doesn’t really know what to do with that information. He doesn’t know what to do with that sense of guilt, of pain. His reaction—and I think it’s something that he’s learned from the people that he’s around—is to shut down. To compartmentalize. To oftentimes resort to humor to make sense of stories. This is something that I saw firsthand a ton. When I was a public defender, every Friday, and often more than that, we’d meet after work at a bar. We’d sit around and have drinks and talk about the stuff that we saw over the course of the week. It was horrible shit. Every week. It was not a therapeutic discussion.

It was more just sharing in this painful experience in a way that let you know that other people were suffering the same way that you did. But I think that that is not processing. I think that that is something else. I think it’s probably more like a compulsive recreation of these things that we’ve been going through. When you asked me earlier about the process of writing this book, I think that was what was happening when I was starting to write. I was doing compulsive recreation rather than processing. That’s why this book took me eight years to write. It took me forever. My first book took me like a year and a half. There was a lot of thinking behind it, and it changed a lot.

One thing we haven’t talked about is his friend Jasper, who is mostly in the flashbacks, but he’s a drug trafficker who is bringing drugs from California into Nevada and then selling them.

Absolutely. But you know him, so “drug trafficker” isn’t the first label that you think of, right? I don’t know if you have people that you know in your life that are like this. If you look at what the charging documents are, then they have titles like “drug trafficker,” but they’re just people you know. They’re people that we’ve grown up with, and we just become accustomed to and familiar with. This was my experience when I was a public defender. I had friends from before I was a lawyer that I kept in contact with. This was during cannabis prohibition, and this was pretty common. I don’t want Jasper to be representative of anything, but I hope that he shows that the people that end up in the courtroom are not different than the people that end up in your house most of the time. There’s also a tendency to say, okay, that might be true if you’re young, or if you hang out with people that do a lot of drugs, but I don’t think that’s true at all.

Look at laws that are on the books versus laws that are enforced. If you look at prescription drug possession, for example, how many people that live in the suburbs that don’t have criminal records have a felony offense sitting in their cupboard somewhere? I think the percentage would be very high. The only difference is how they’re policed and how they’re prosecuted. I love Jasper as a character. He’s a minor character. I think you could just say, maybe he doesn’t belong in the book, but he feels real in a way that Santi admires.

I think so. And I know those people, too. And it takes Santi a while to realize that this isn’t a side hustle his friend does, like he did when they were in school. He’s introduced as a person before we learn how he makes his living. He’s a part of the fabric of this town. In every sense.

No question. The other thing with Jasper is that I wanted to capture some of the libertarian spirit of Nevada. I know so many people that are like this. They are sort of ethical lawbreakers. Like for Jasper, selling drugs is a way to get by, but he is raised in this tradition where he thinks that the government should not really be policing what you’re doing in that way. He is somebody who is probably politically very left, but also probably has three pistols under the seat of his car. I felt it was important to have somebody like that from Nevada and in the book

I wanted to ask about legal thrillers because I think the book responds to the genre and the shape of the legal thriller in a similar way to how your earlier novel All That Followed responded to the thriller.

I’m glad to hear that. I hope I’m playing with it in a way that’s interesting rather than just playing with it for the sake of playing with it. I love legal thrillers. Part of what makes them interesting is their tendency to surprise. I hoped in writing this and thinking about the structure and centering it around the attorney as opposed to the client, that it would be surprising in some ways for readers The other thing is—without giving away too much—I was responding to the stakes of a book where you know the accused is a monster or the accused is a saint. To me, that’s not super interesting. There’s not a lot of moral complexity in the idea of whether a superhero is redeemed or whether a supervillain is convicted. The real moral turbulence for me resides in those cases where there aren’t really any winners or losers. Well, there’s a lot of losers usually.

I wanted a book to reflect the experience of being a public defender a little bit more, but also give space for the reader to decide what happened and who are the good guys and who are the bad guys. To really start larger discussions about the criminal justice system as well. Hopefully it’s an exciting book, but hopefully it’s also interrogating what it means to be a moral actor in the criminal justice system. I like books that give me space to make those moral decisions and I hope the book is doing a bit of that.