“The setting.”

This is always my answer at a book event when someone asks the inevitable question: What comes first when you write a thriller?

Crime writers and their processes are as varied as the stories they tell, and I’ve heard this question answered every sort of way. For some, the characters come first, living and breathing in the author’s head long before a single sentence hits the page.

For others, it’s the quandary—the great what if that their novel seeks to explore. Some writers even begin with the ending, the twist, the puzzle-piece moment that locks everything else into place.

For me, it’s always the landscape. The personality of a town. The feel of the woods.

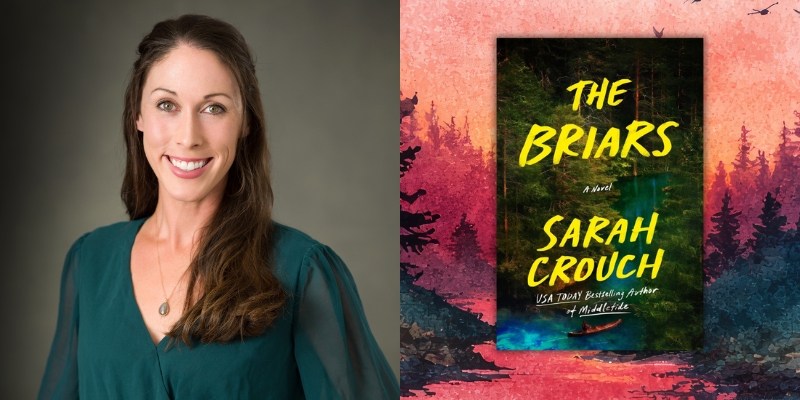

When I sat down to write The Briars, I knew exactly where the novel would live.

I grew up a stone’s throw from Mt. St. Helens and was raised on stories about the eruption. Like tourists, my family took the winding highway around the mountain to gawk at the ruined north face, but it was the south side that always held my fascination.

The blast was lopsided, shearing the mountain unevenly and leaving the southern face untouched. Pristine. Not a pine tree out of place. That pocket of wilderness at the damp, wild heart of Washington State is lush and unforgiving—the perfect place to set a murder mystery spanning two crimes and vast miles of untamed forest.

Next, it was time to choose a protagonist who could bring the setting to life. I wanted a character who would not just exist in this landscape, but thrive in it. Wrestle with it. Stand up to it when the time came.

I learned while writing my debut, Middletide, that the forest is a wonderful accomplice to murder—hiding evidence, isolating characters, and creating false leads—but I had yet to write a protagonist who was truly up to the task when the wilderness itself became the antagonist.

One of the great challenges in novel writing is to create characters who break molds without becoming clichés. This is tricky in any genre, but particularly in crime fiction. Crimes need solving, so crime novels need investigators. Murder mysteries would have no ending if no one stepped up to solve the murder, but because of that necessity, the same familiar faces seem to appear over and over on the page.

You know the roster. The quirky small-town sheriff. The jaded city cop. The no-nonsense female investigator. The smooth, lone-wolf detective. A few chapters in, they settle comfortably into their tropes. And, don’t get me wrong, I love a quirky small-town sheriff, but in writing The Briars, I felt it was time to toss a new hat into the ring.

Enter the game warden.

While I can name a handful of authors who have explored this profession in their stories, the game warden remains—if you’ll forgive me—a criminally underused protagonist. It’s an unusual profession, perched at the crossroads of wilderness skill and law enforcement, a job that requires empathy, courage, and a level head, but also the ability to read people and pick up on subtle deception—fertile ground for characterization, to say the least.

I’ll admit, I knew almost nothing about the daily duties of a game warden when I started writing, only that the job seemed to attract a specific sort of individual—someone at ease with silence and solitude, yet unafraid of confrontation when pushed. With that rough template, I began shaping Annie Heston, the main character of The Briars. And as the research piled up in a separate Word document, she began shaping the novel right back.

As the story grew roots and the word count ticked higher, Annie became a bridge. She stepped in to occupy the liminal space between the law and the wilderness: a sworn officer whose jurisdiction begins where the pavement ends.

This duality allowed her to move fluidly between the two worlds—the human system of law that governs the small mountain town of Lake Lumin, and the wild system of nature that rules the dense, piney foothills at its back. A fortunate link, since the crime at the core of the novel is tangled up in both.

When Annie flees her failed marriage in Oregon and arrives in Lake Lumin, she is an outsider in every sense of the word. Her profession keeps her largely in solitude—patrolling the fringes of a community already wary of any who are not their own.

But the imminent danger of a prowling cougar sends her into town to warn citizens of the threat. In doing so, she forms a tentative connection with Daniel, a reclusive carpenter living in an old boathouse on the lake.

The game warden remains—if you’ll forgive me—a criminally underused protagonistAnnie finds purpose in her duties and quiet solace with Daniel, but when the body of a young woman is found in the briars that border his remote property, Annie must draw on her wilderness instincts to track down answers hidden in the wild, while also helping local law enforcement tighten their circle around the suspects in town.

Not quite a cop, not quite a park ranger, Annie has access to everyone and allegiance to no one. This unique role allowed me to flex her moral compass and push her into dangerous territory both geographically and socially, adding layers to the central mystery that would never have existed if I’d relied on conventional investigators alone.

As I wrote, I realized the story wasn’t shaping Annie—Annie was shaping the story. She sent out new shoots, new paths to explore, adding a wonderful sense of discovery to the writing experience and, I hope, to the reading experience as well.

Writing Annie taught me that a crime novel comes alive not just in the mystery it solves, but in the wild places—and wild people—who refuse to fit neatly into any one world.

***