Monday, March 27, 1871

“At ten minutes to ten o’clock, the Bailiff of the Court entered the door and flung wide both its leaves. A figure entered, dressed in black and thickly veiled, leaning upon the arm of Dr. Trask. It was Mrs. Fair, and behind her walked her mother and little daughter. When she had advanced a few paces into the room she threw back her upper veil, leaving over her face only a thin fall of black tulle, through which her features were plainly visible . . . Mrs. Fair has doubtless been a handsome woman, though anxiety and long sickness have left their indelible marks upon her face . . .”

— San Francisco Chronicle

The trial of Laura D. Fair for the murder of Alexander Parker Crittenden began on a brisk, cloudless spring morning at California’s imposing Fifteenth District courtroom in San Francisco, the Honorable S. H. Dwinelle presiding. Because of the intense amount of publicity surrounding the case, Judge Dwinelle had insisted that three policemen be stationed at the entrance to the spectators’ enclosure to prevent members of the public from entering. Only reporters, attorneys, and those directly involved in each day’s hearing would be allowed to witness the proceedings. Always a stickler for decorum in his courtroom, Judge Dwinelle was determined to keep this trial as uneventful and by-the-book as possible.

The judge’s hopes, however, were doomed from the start. Almost six months had passed since the fatal pistol shot was fired on the El Capitan ferry, and the city’s fascination with the murder had shown no signs of abating. During that time, the Fair-Crittenden case had dominated virtually all other subjects of conversation. Few could resist the lurid tale of the twice-divorced, twice-widowed young woman who had gunned down her longtime paramour—one of the most prominent figures of the city’s legal community—right in front of the wife he refused to abandon for her. And now that the trial was finally starting, after weeks of legal maneuvers and pretrial motions, the public’s obsession with the case was as consuming as ever. Far more people wanted to watch the spectacle than any California courtroom could hold. Three policemen at a doorway would prove no serious obstacle to those who really wanted to get in.

The man principally responsible for seeing that justice was done in this case was District Attorney Henry H. Byrne. A native of New York City, Byrne—like Judge Dwinelle and so many of the other principals involved in the case—had come to San Francisco some twenty years earlier, penniless and without reputation but eager to succeed in the wild new territory opened up by the discovery of gold. Like his colleagues, he had failed to attain fabulous wealth as a miner but instead had claimed a place for himself in the infrastructure of urban civilization that rapidly coalesced in Gold Rush San Francisco. Two years after his arrival, the neophyte lawyer had already risen to become the city’s district attorney. Now nearing fifty, he was serving his fourth term in the office. And while he was physically unprepossessing—one contemporary remarked upon his short stature, stiff carriage, and “sharp, harsh, and screeching” voice—he compensated for these deficits with exalted eloquence. “Harry” Byrne, as he was usually called, was famous for peppering his courtroom speeches with high-toned literary allusions and, when necessary, a scathing invective that could wound both friend and foe alike.

The case he was about to argue would be the most important of Byrne’s career so far, and he had good reason to be optimistic about its outcome—not least because he was satisfied with his jury. During the day and a half of voir-dire examinations to assemble the panel, nearly every potential juror had admitted that the defendant was probably guilty; the twelve men who had survived defense challenges were those who’d merely expressed a willingness to be persuaded otherwise by the evidence. The one member of the jury pool who’d claimed sympathy for the defendant and disdain for the victim (“I think any man who acts that way ought to be shot,” he admitted) had been quietly excused. So it was a sympathetic audience that Byrne approached on the afternoon of the prosecutor’s opening statement. As expected, the courtroom was full to the rafters—all seats occupied, and with standing spectators jammed into every space available. It was all the three policemen could do to keep the aisles clear for the reporters and observing lawyers to come and go.

“Gentlemen of the jury,” the DA began, one hand as ever in his waistcoat pocket in a classic lawyerly pose. “The defendant at the bar, Laura D. Fair, is charged with the commission of the crime of willful murder, alleged to have been committed on the third day of November last, on board a steamer called El Capitan.”

For this opening statement, Byrne chose to lay out the facts of the case as simply and straightforwardly as possible. No one, after all, doubted that it was Laura Fair who had fired the shot that killed A. P. Crittenden. The question was whether it was murder in the first degree, which required a demonstration of malice aforethought. So Byrne began by stating exactly how the prosecution would establish the necessary elements of premeditation and motive. Premeditation was self-evident: Mrs. Fair had made threats of violence several times in the past; she had acquired the murder weapon three days before the shooting; and she had thought to take a black veil aboard the ferry in order to hide her identity. There could be no doubt: “The defendant . . . took passage on that boat for the purpose of accomplishing what she did so successfully—the shooting of Mr. Crittenden.”

As for motive, it was equally obvious: Crittenden had called his wife and family back to San Francisco in order to reconcile with them and end the seven-year affair with his mistress. Naturally, Laura Fair sought to avenge this rejection—by destroying the man she could not have for herself, in front of the woman who had kept him from her.

During the DA’s recitation of these points, the defendant, looking pale and fatigued, sat in a rocking chair between her lawyers at the defense table, listening in grave silence. “Her expression is that of great sadness, weariness, and passive suffering,” one newsman reported. Such a face, he felt, would likely be an aid to the defense in this case. What’s more, Mrs. Fair’s bright golden hair—worn today tied back in short curls—would also have a softening effect on the jury’s sympathies, as would her blue eyes, well formed eyebrows, and appealing features.

But Harry Byrne, while fully aware of the defendant’s potential to elicit an all-male jury’s pity, was counting on there being no such effect with this particular group. These were practical businessmen who would understand the importance of the city’s image in the mind of the general public. “That, gentlemen,” the DA concluded, after a re- markably brief opening statement, “is substantially the case on the part of the people . . . So far as the definition of murder in the statute can fix it, this was a willful, deliberate murder, and in the name of the law we pronounce her guilty thereof, and ask at your hands a verdict of guilty.” It was thus a straightforward case, open and shut—or that at least was what DA Byrne hoped for.

In truth, there was nothing straightforward about the trial that would unfold in that courtroom over the next four weeks. For this would not play out like the typical local murder case. The defendant was a woman, for one thing, and while female murderers were not unknown in Victorian-era California, Fair’s gender was still enough of a novelty to cause a sensation on that score alone. But there were other, more fundamental, issues involved. At a time when reputable women were expected never to step beyond the private realm of home and family, Laura Fair had made a lifetime practice of invading the public sphere—as an actress, as a successful businessperson and investor, and as the unapologetic mistress of a prominent (and married) man. This brazen murderess, in other words, had posed a grave threat to the social order even before she ever pulled a trigger. Would a jury of respectable men feel sympathy for a woman like that?

Ultimately, the trial of Laura Fair would prove to be deeply controversial, provoking bitter debate nationwide and challenging long-held beliefs of a populace still searching for moral consensus after the shattering disruption of civil war. For many, even for those just looking on from the sidelines, the ethical stakes could hardly have been higher. By calling into question fundamental assumptions about the sanctity of the family, the value of reputation, and the range of acceptable expressions of femininity, the case would become profoundly divisive; it would cause rifts and arguments between husbands and wives, provide endless fodder for newspaper editorialists, and inspire paroxysms of indignation among sermonizing clergymen. Even such prominent national figures as Mark Twain, Horace Greeley, and Susan B. Anthony would be drawn into its orbit.

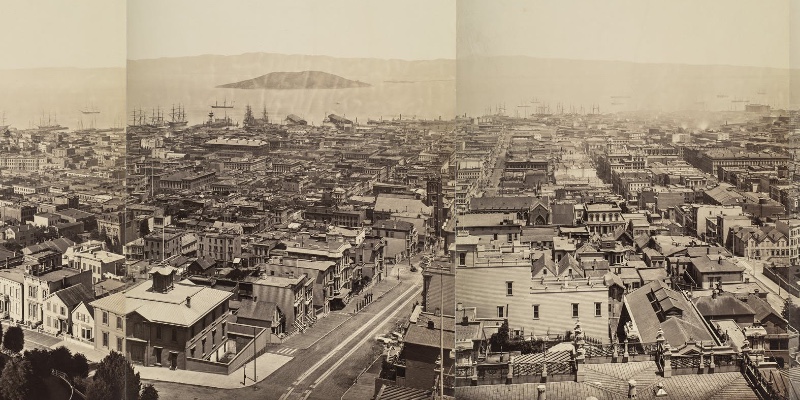

But while the spectacle of the trial would make front-page headlines from coast to coast, its outcome would be of particular importance to the city in which it unfolded—San Francisco, a still-adolescent metropolis in the early 1870s, hoping to shed its Gold Rush–era reputation as a raucous and untamed frontier town. For a city eagerly trying to establish its name as a mature, orderly, and law-abiding place, the kind of violence and depravity exemplified by Laura Fair’s crime demanded the severest punishment. Only a death sentence would serve as a clear demonstration to the world (particularly to the East Coast capitalists whose investments the city needed in order to grow) that the rule of law had finally come to the former Wild West.

So for District Attorney Byrne and many of the other community elites of San Francisco, there could be only one acceptable outcome to what he called “the most important case that has been tried upon the Pacific coast”—a simple and straightforward verdict of guilty on the charge of murder in the first degree. But for those who knew of the events that had preceded the crime on the El Capitan ferry that November night, the matter of Laura Fair’s guilt or innocence would be significantly more complex.

___________________________________