Let’s say you have a successful series of detective novels, anchored by a core set of well-established characters — a private detective, his wife, and his sidekick — who, in book after book, are threatened by and finally defeat formidable criminal antagonists.

This detective is smart, smooth, logical, obsessed with his work, and sometimes troubled by that obsession. His equally smart wife respects his ability and devotion to his work, but keeps pushing for more balance in their life together, more closeness. His sidekick is skeptical of everything and everyone, constantly challenging the detective’s ideas, but he’s always there when the chips are down. The cases that draw the detective’s involvement are invariably complex murders with cleverly concealed motivations.

An anonymous narrator tells the stories from the detective’s point of view. The reader sees everything the detective sees and is privy to his thoughts and feelings. The genre is an amalgam of police procedural, classic puzzle mystery, and contemporary thriller. The setting is rural, pastoral, economically depressed.

The tone is objective, the descriptions realistic. Main characters are three-dimensional, minor characters are two-dimensional. (I believe it was E.M. Forster who made the interesting observation that the essence of a two-dimensional character can be expressed in one short sentence, while three-dimensional characters have internal contradictions and a range of possible behaviors that make a one-sentence summary impossible.)

Finally, let’s assume that this multi-volume series has a large audience of loyal readers who look forward to the next installment with eager anticipation.

In a situation like that, does innovation make sense?

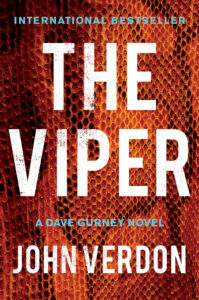

As the author of the internationally bestselling Dave Gurney mystery-thrillers, I faced this exact question when my editor suggested that it was time to “shake up” the series — to change the familiar plot dynamics in a way that would push the characters in new directions.

To avoid spoilers, I won’t reveal the details of how this shake-up was accomplished and how the changes made the latest Gurney novel, The Viper, different from the seven that preceded it. However, the process incorporated some principles that I believe would apply to any series.

Let’s look first at that basic question: Why change a winning formula?

Well, right off the bat, I can think of two reasons. The first is that familiarity is a double-edged quality in any relationship. It can provide readers with a sense of comfort and pleasant anticipation. On the other hand, it can lead to a diminishing sense of excitement and even boredom. The second reason for change is that, no matter how fond we are of the familiar, we also like to be surprised.

So, the challenge for the author becomes how do you introduce the sort of changes that are likely to strengthen rather than weaken the all-important bond between the series and its reader?

Let’s look first at the elements of a series where it might be possible to introduce something dramatically new and different. Some obvious ones are narrative tone, setting, degree of realism (especially in the treatment of sex and violence), cast of characters, and character relationships.

The first thing that occurred to me is that the risk-reward ratio of introducing changes varies considerably from element to element.

For example, narrative tone — breezy, grim, ironic, intimate, comic, etc. — is so basic to the spirit of a series that it would be difficult to change it without so disrupting a reader’s experience that the bond would be broken. I’m not saying that a series can’t, like a dramedy, mix genres — only that a dramedy needs to be that from the beginning.

Similarly, the degree of closeness that the author establishes between the reader and the details of a crime is so viscerally linked to matters of taste and tolerance that alterations in that area run the risk of reader alienation, particularly in the matter of vividness — for example, how much of a sadistic murder occurs in close-up real time as opposed to offstage.

A change of setting can provide some renewed interest, and there’s not much risk in it — unless the original setting is essential to the concept and feeling of the series. I wouldn’t want Miss Marple to start solving crimes in urban slums. But I’d happily follow Sherlock Holmes anywhere. And part of the interest in a James Bond adventure is a new exotic locale for each one. Changes of setting alone, however, may not be enough to give a series any real refreshment.

That brings us to two areas in which I believe major changes can be introduced and, with some care, major downsides avoided. The first is in the cast of characters. A colorful new player can be brought into the arena, either as an addition to the existing cast or as a replacement for a departing member. This can be a game changer, with two caveats.

If the new character is an addition, care must be taken to give them an appropriate role. By this I mean the manner in which they relate to the protagonist’s quest (e.g., a central detective’s search for the truth). Are they supportive or obstructive? Are they cynical or trusting? Are they rule followers or mavericks? Most important of all, does their fundamental way of relating to the quest contribute a new element to the series, or is another character already performing that function? If the latter is the case, the basic orientation of the new character may need some rethinking.

If the new character is not an addition but a replacement, the challenge will be how to incorporate in them the essential contributions of the departing or incapacitated one — but with significant differences in look, tone, and style. (If there’s no substantial difference, why make the change?)

Another promising area for series refreshment lies in the various relationships among ongoing characters — and this brings us back to Forster’s comment on two-dimensional vs. three-dimensional characters.

The more complex a series character is, the more opportunity there is for behavior that is both surprising and credible. Conversely, the flatter and more limited character is, the more difficult it is to change their outlook or actions without obliterating their one-sentence identity. Cardboard cut-outs lack flexibility. So, perhaps our best and safest chance of shaking up the dynamics of a series without turning off our loyal readers is through the application of new pressures on our three-dimensional characters — pressures that change their behavior and their relationships dramatically yet believably.

Putting familiar characters under pressures they’ve never experienced before can produce decisions and actions they’ve never taken before. This in turn creates for the loyal reader a substantially different experience — an eye-opener, if you will.

In the process of introducing changes like this in the latest Gurney adventure, it became clear that the new behavior — however startling it may be — must have roots in the established world of the series. For example, if a key relationship suddenly breaks apart, it should do so along a previously established fault line. The change must ultimately be a believable one, consistent with the core identities of the characters involved.

Major unanticipated behavior and the ongoing consequences of that behavior can add new life to a story and, by extension, a series. But unbelievable behavior, whether major or minor, does exactly the opposite.

It’s a bit like the old dramatic truism that if a character shoots someone in act three, the audience should get a glimpse of the gun in act one.

***