‘Glasgow is a magnificent city,’ reflects one of the characters in Alasdair Gray’s Lanark (1981); ‘Why do we hardly ever notice that?’ ‘Because,’ another character replies, ‘nobody imagines living here.’ Over the past half-century, some of the most vivid attempts to imagine living in Glasgow have been crime novels, from the Laidlaw trilogy of William McIlvanney to the fictions of Frederic Lindsay, Denise Mina, Louise Welsh, Christopher Brookmyre and others. And despite the assertion that ‘nobody imagines living here’, those novels take their place in a venerable tradition of writing about Scotland’s western metropolis.

One of the first novelists to write about Glasgow did so, not in a work of fiction, but a travelogue. In his Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-7), Daniel Defoe presented Glasgow as an elegant ‘city of business’, a boomtown whose prosperity depended on the recent Act of Union with England which ‘open’d the door to the Scots in our American colonies’, allowing merchants on the Clyde to grow rich on the Virginian sugar and tobacco trades.

At the same time, in his journalistic writings, Defoe identified a lawless underclass, the so-called ‘Glasgow rabble’, who not only rioted against the Union but stood as a threat to the city’s emerging prosperity. For Defoe, Glasgow was a city of contradictions—the place where a commercial British modernity reached its apotheosis, but also the place in which that modernity was menaced by popular lawlessness.

Defoe’s ambivalent vision of Glasgow casts a strong shadow over early novelistic depictions of the city, such as Tobias Smollett’s The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771) and Walter Scott’s Rob Roy (1817). Crime fiction, too, has drawn on Defoe’s vision of a city riven between entrepreneurial respectability and mob violence, not least since these categories bleed into one another. Not only have Glasgow gangs been set up on a ‘business’ footing, but ‘business’—in a city built on the profits of chattel slavery—has often assumed a brutal character. As a visitor to Glasgow tells a crowd of its inhabitants in David Pae’s Novel, Lucy, The Factory Girl (1860), ‘There is not a stone in your dirty town but what is cemented by the blood of a negro’.

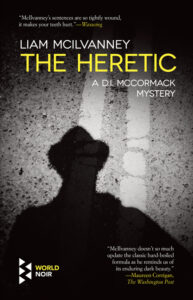

In my own new novel, The Heretic (2022), these two worlds—the ‘city of business’ and the ‘Glasgow rabble’—collide. The novel opens with the vicious murder of a city businessman, Gavin Elliot, whose own professional ethics leave a lot to be desired. Rival gangs—the Maitlands and the Quinns—battle for control of the city’s illicit trades. Along the way there are arson attacks in the ‘tinderbox’ tenements, armed standoffs, and a bomb blast in a Northside pub: more than enough, in other words, to occupy my investigator, DI Duncan McCormack, and his sidekick DC Liz Nicol.

Writing about Glasgow in the 1970s has proved to be a liberating experience. Untethered from mobile devices, characters can actually interact with other humans. Without cellphones in which to bury their noses, they are free to notice the world around them. And it’s been fun bringing that half-forgotten city back to life, not least because Glasgow, more than most cities, has taken such pains to leave its past behind.

In the 1980s the city authorities embarked on a determined effort to improve Glasgow’s image, aiming to shed the old associations with slum tenements, gang violence and deprivation. The ‘Glasgow’s Miles Better’ advertising campaign (partly based on the ‘Love New York’ initiative) emphasized Glasgow’s extensive parkland and its cultural riches, from the architecture of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson to the paintings of the Glasgow Boys and the contemporary literary renaissance inaugurated by James Kelman, Alasdair Gray and Janice Galloway.

Around the same time, the city’s soot-encrusted tenements and public buildings were sandblasted to reveal the beautiful hues of the native red and blond sandstone. This process of reimagining the city climaxed with showcase public events like the Glasgow Garden Festival of 1988 and Glasgow’s reign as European City of Culture in 1990, which happened to be the year I graduated from Glasgow University.

The transformation in Glasgow’s image was no mere cosmetic makeover. It spoke to real changes taking place in the city and emphasized aspects of the city’s culture that had often been overlooked. Still, there was a feeling in some quarters that the city’s intractable problems of poverty, crime, poor housing and drugs were being airbrushed out of the picture. And in this context it’s hardly surprising that so much recent crime fiction about Glasgow—not just my own Duncan McCormack books, but the novels of Alan Parks, Denise Mina’s The Long Drop (2017), and Craig Russell’s PI Lennox novels—push back beyond the ‘City of Culture’ to an earlier era when Glasgow wasn’t ‘Miles Better’ but just as compromised and ambivalent as it always was. We are returning to a grittier, noir Glasgow—what Denise Mina calls ‘the old boom city, crowded, wild west, chaotic’.

In my own case, there is another advantage in writing about 1970s Glasgow. I live in New Zealand, twelve thousand miles away from my West of Scotland roots. My first two novels—All the Colours of the Town (2009) and Where the Dead Men Go (2013)—were political thrillers with a contemporary setting. Gradually, however, I came to accept that writing topical thrillers about a country I left several years ago was growing more implausible with every passing year. Writing about a historical Glasgow—or at least the Glasgow of five decades ago—was both more appealing and more practical. In some sense we are all equally distant from the Glasgow of 1975. My distance in space is nullified by the distance in time.

I have also been encouraged by the notion that distance lends perspective. The great Yorkshire writer, David Peace, wrote his Red Riding Quartet, a truly harrowing series of novels dealing with the Yorkshire Ripper murders, while living in Tokyo. At one point he returned to live in Yorkshire but the plan backfired and he was back in Japan within a couple of years. He found that he couldn’t write about Yorkshire in Yorkshire. I’m hoping that something similar holds good for my own attempts to write about Glasgow.

That said, when I was home for six months in 2018, I made a point of visiting many of the locations I would write about in The Heretic. Some of the book takes place in the district of Maryhill in the city’s northwest. A bomb goes off in the Barracks Bar, a fictional pub on Garrioch Road. My detective, DI McCormack lives in Caird Drive, on the boundary between Partick and Partickhill (which is also the home turf of another fictional 1970s Glasgow detective, Harry McCoy, in the novels of Alan Parks). McCormack works out of Temple Police Station, just north of Anniesland. I pounded the streets in all of these areas but, in the end, I’m not sure that this kind of ‘research’ matter much. Your goal, in a novel, is to render the city through the eyes of your characters. It’s their imaginative vision that counts. As Alasdair Gray put it forty years ago, the task is quite simple: ‘imagine living here’.

***