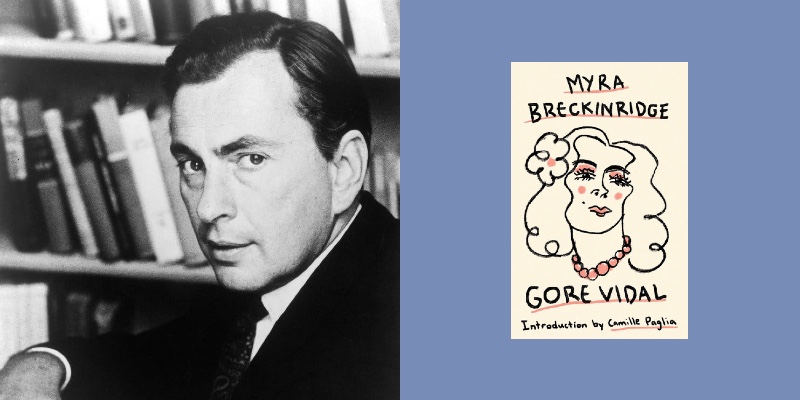

Gore Vidal was intellectual culture’s reigning champion of social liberalism and secular advocacy for decades. His famous wit indicates that he would appreciate the irony of someone awarding him the title of “prophet,” but it was well-earned. His series of novels chronicling American history act as a telescope into the past that, somehow, allows for clarity in the present, while his essays, perhaps the best in American letters, remain profound, amusing, and instructive.

Despite all of his literary and polemical accomplishments, none of his works matched the futuristic gaze of the satirical, postmodern novel, Myra Breckinridge. Fifty years ahead of its time, the story of a man who transitions into a woman, dedicating herself to the demolition of patriarchal, homophobic gender norms, is a rollicking ride of entertainment, humor, and incisive social commentary. Published in 1968, it reads as if it could be published in 2028. Countering the cliché that a prophet is “unknown in his time and country,” it quickly sold two million copies, and became the subject of endless discussion, debate, praise, and pejoratives.

“I never quite had that experience, an otherworldly voice, one that took me over. I felt like a medium,” Gore Vidal said when telling an interviewer how he wrote Myra Breckinridge. He recalled sitting down, first thing in the morning, in his Roman apartment, and hearing Myra say, “I am Myra Breckinridge, whom no man will ever possess.” Vidal’s first communiqué with the otherworldly voice doubles as the opening line of the novel.

With those words, Myra leads Vidal, who acting as the medium, leads the reader through a surreal exploration of Hollywood, Western sexual mores, the campaign against them, and the foibles of American masculinity.

The transgendered anti-heroine announces a mission to remake men, especially heterosexuals who occupy the center of society. Vidal was two weeks into writing the novel when he realized that Myra was a trans woman, and the depiction of her desire to destroy traditional masculinity is, at once, revolutionary and satirical. The latter gives plenty of opportunities for amusement, because Myra’s acts of villainy read like the fevered nightmares of the religious right, whereas the former emerges in the philosophical sections. Vidal intersperses the action with dialogue and disquisitions in which Myra provides her theory of gender. It was a theory that no political camp in the 1960s or ‘70s could fully comprehend – not even the fledgling gay rights movement – but has now become vogue. Myra even uses the keyword of our times.

“The fluidity which I demand of the sexes is diametrically opposed to Mosaic solidity,” she declares, “…For it is demonstrably true that desire can take as many shapes as there are containers. Yet what one pours into those containers is always the same inchoate human passion, entirely lacking in definition until what holds it shapes it. So let us break the world’s pots, and allow the stuff of desire to flow and intermingle in one great vicious sea…”

Myra’s (and Vidal’s) manifesto functions as motivation for her calling in life. A serious film afficionado, she secures employment at an elite Hollywood academy for aspiring actors. She teaches courses in “Posture and Empathy,” and off the books, “Female Dominance.” Because she wants to demolish traditional, patriarchal masculinity, she goes straight to the source of macho propaganda, the lingua franca of American culture – the film industry. If she can help breed a new leading man, who can then project and propagate a new, fluid sexuality, she will have triumphed at cultural transformation.

Early in the novel, she meets her target – Rusty, a charismatic and handsome young man in the mold of Marlon Brando, James Dean, or Robert Redford. He wears “faded jeans and desert boots,” which Myra calls a “costume.”

“It is costumes that young men now wear as they act out their simple-minded roles,” Myra elaborates, “Constructing a fantasy world in order to avoid confronting the fact that to be a man in a society of machines is to be an expendable, soft auxiliary to what is useful and hard. Today there is nothing left for the old-fashioned male to do, no ritual testing of his manhood through initiation or personal contest, no physical struggle to survive or mate. Nothing is left for him but to put on clothes reminiscent of a different time; only in travesty can he act out the classic hero who was a law unto himself, moving at ease through a landscape of admiring women. Mercifully, that age is finished.”

In one paragraph, Vidal, as Myra, manages to capture the metamorphosis of masculinity – the consequence of economic, cultural, technological, and political changes – that continues to trouble the psyches of reactionary men, and manifest in the political backlashes of laws against women’s medical autonomy, biases against women in power ranging, such as Hillary Clinton and vice president, Kamala Harris, obsessions with guns, and hateful campaigns against LGBTQ youth, most especially book bans targeting stories exactly like Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge (I hope this essay doesn’t give a would-be book confiscator any ideas).

Myra posits that the age of machismo is finished, and she dedicates herself to eliminating its last cultural remnants. While almost never thought of as a “crime novel,” Myra Breckinridge hinges on the crime of identity theft. Myra has transitioned from Myron, a revered film critic, and forged documentation of her past to secure her position at the academy. Myron, everyone believes, is missing – a misperception that Myra is more than willing to encourage. The novel climaxes in a far worse crime, which Vidal plays as a farcical absurdity.

As part of her campaign to alter the masculinity of Rusty, and thereby the sexual culture of America, Myra, who claims to have previously worked as a nurse, insists on examining the aspiring actor. She subjects him to a series of sexual humiliations that culminates in a violation using a strap-on (Myra insists it is a medical instrument).

Following the assault, Rusty turns brutish and violent in an act of obvious compensation. His girlfriend leaves him, allowing for Myra to then seduce her, test her sexuality, and eventually, live happily ever after, following her transition back to Myron. The second transition is the result of a traumatic car accident. She must have her breast implants removed, and can no longer obtain the hormones necessary to remain Myra. The novel ends happily for the hard-to-categorize couple, and yet lingering questions remain for the United States – questions that now excite, fascinate, and frustrate millions of Americans: What is gender? Is it malleable? Is fluidity the future?

Vidal was on the receiving end of many attacks following the publication of Myra Breckinridge. No stranger to controversy, he had already endured temporary banishment from the New York Times Book Review for his novel, The City and the Pillar – arguably the first American novel to depict same sex attraction as normal and healthy. Many right wing critics rebuked Myra Breckinridge as “pornography,” most infamously William F. Buckley during their 1968 television debates during the Democratic and Republican Conventions. The debate exploded when Buckley called Vidal a “queer” (then, an anti-gay slur) and threatened to “sock him in the goddamn face.”

Vidal wrote that causing Buckley to reveal his true nature, which he likened to Buckley’s forehead opening and a cuckoo bird flying out, was one of his great achievements. Buckley would later write that the federal government should force men with HIV/AIDS to get tattoos identifying their positive status on their buttocks. It is good to keep these stories in mind considering that Buckley is one of the figures that media commentators evoke when discussing a supposedly enlightened, kinder American right in comparison to the contemporary monstrosity.

Although Buckley was old money, upper class, Myra has a line in the novel that applies to him, and most of the book banners: “Like most members of the lower classes, they are reactionary in the truest sense: the unfamiliar alarms them and since they have had no experience outside…their ‘peer group,’ they are, consequently, in a state of near-panic most of the time, reacting against almost everything.”

In the same passage, Myra forecasts the election and cult-like popularity of Donald Trump, saying of her male students “drawn to violence” and “totalitarian minded,” “I am convinced that any attractive television personality who wanted to become our dictator would have their full support.”

Vidal wrote a decent sequel to Myra Breckinridge, called Myron, and Hollywood made a dreadful film adaption of the first novel, starring Raquel Welch. The author called the film an “awful joke,” even though he never saw it. After reading a copy of the script, he refused to ever watch the crucifixion of his brilliant book.

The US had made remarkable progress since the novel’s publication. The then-incomprehensible sexual analysis has gone mainstream, gay marriage is legal, every state has prohibitions against employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gays can openly serve in the military, and transgenderism is no longer taboo. Moving into a consequential election, American culture is still battling with the “totalitarian minded” and those “drawn to violence.”

There is no better time to revisit Gore Vidal’s prophecy.