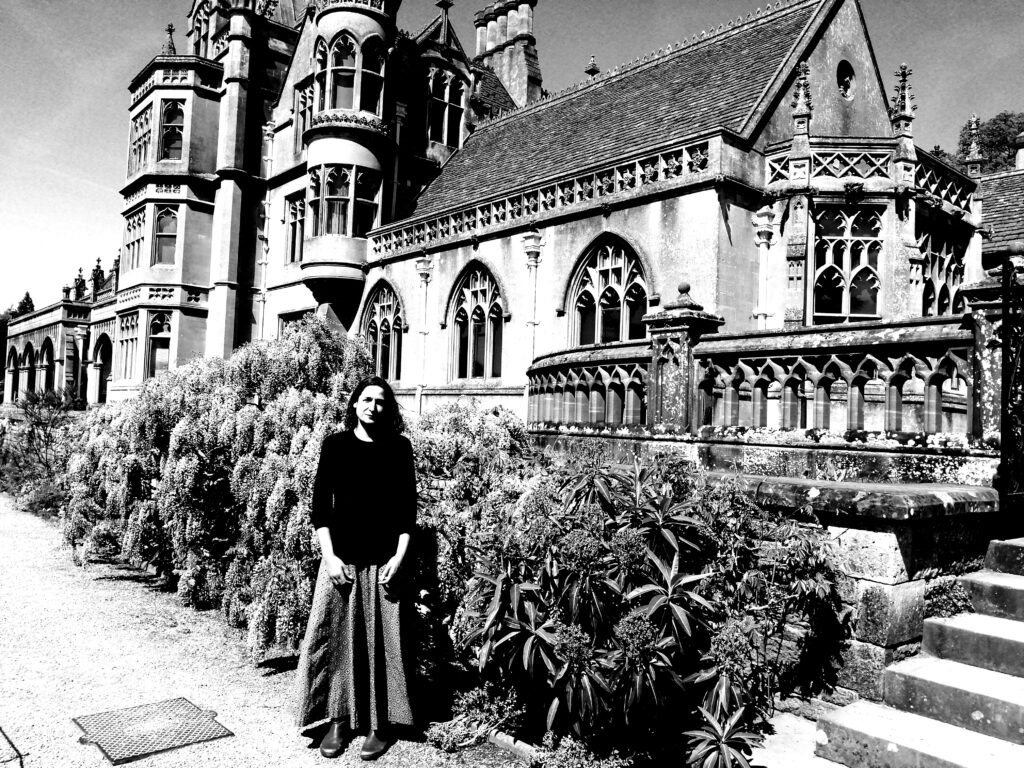

In 2002, the magnificent neo-Gothic mansion of Tyntesfield near Bristol was acquired by the National Trust. Shortly afterwards, I joined a small group for a special tour of the upper rooms.

It was winter. We huddled in the hall, cold and dim and museum like, before slowly climbing the great carpeted staircase, with its treacherous swags of loose wool. Around the gallery we went, past closed doors, gaping passageways and roped off attic stairs.

On the far side, we entered a narrow, corridor type room, and saw the bed in which the reclusive last baron had not only died but was said to have slept all his life. “This was his father’s old dressing room,” we were told. “He was only three when his father died.”

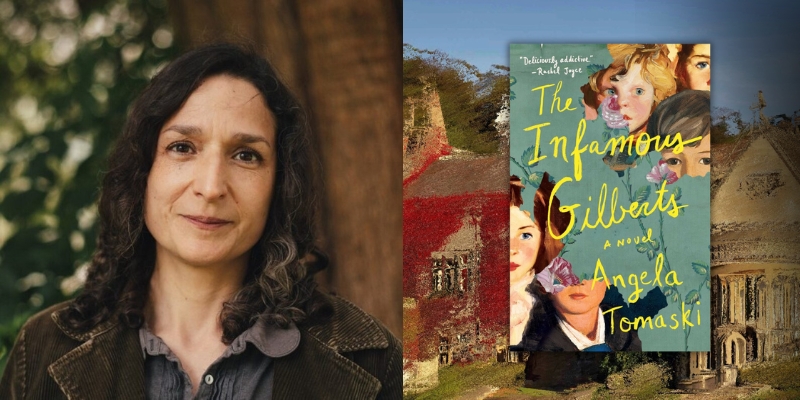

courtesy of author

courtesy of author

I remember an ugly brown carpet, flattened in a path from the door to the bed, a pair of squashed slippers, and the smell of coal tar from a small tablet of orange soap, thin and cracked and see-through at the edges, on the washstand in the corner.

From the narrow bedroom, we went down the servants’ staircase at the back of the house, to the scullery, the butler’s pantry and the kitchen, large and white and empty. I conjured the echoes of long-lost cooks and maids, and the ghost of a solitary man, shuffling towards the kettle with a Pot Noodle.

Like many people, before and since, I fell completely in love.

On my next visit, a few months later, I hurried back upstairs, but the bed and the slippers and the soap were gone. In their place was a small table covered in pamphlets and raffle tickets.

It was a terrible moment. Where was the bed? What had happened to the slippers and the soap? I looked around. It seemed to me that a fair amount of dusting had also taken place. The smell was different too, and the doorhandles shone with a gut-wrenching absence of fingerprints.

Overcome, I retreated to the newly opened café and restored myself with tea and cake.

As I ambled around the formal gardens sometime later, I mused upon the nature of Heritage and Conservation. I am a big fan of the National Trust, with its fervent and seemingly indiscriminate commitment to preservation. Its website is filled with photographic inventories of what might, superficially speaking, be seen as a load of broken old rubbish, but it is a storyteller’s paradise, for each object whispers something about who held it, dropped it, shoved it under a dresser and lied about it.

There is something deeply comforting about a shrubbery painstakingly propagated from the three-hundred-year-old original, and teams of volunteers dusting curtains with tiny paintbrushes and dabbing ancient seashells with damp cotton buds.

It gives a reassuring sense of the value of life. The value of minutia. But while it’s nice to have one’s worshipful sorrow at the loss of one’s own toenail clippings vindicated, where does it end? Realistically, what future is there for a tablet of used soap? Ought it to be kept? Framed? Surely, that is going too far.

Is it respectful, reverential, to preserve someone’s moth-eaten socks and half-eaten bar of fruit and nut, or invasive and even exploitative? Should one’s soap and slippers be buried with one, so to speak?

I don’t know. These are questions for the experts.

Meanwhile, I bent down, surreptitiously plucked a blade of grass from the edge of the drive and slipped it into my pocket.

The weight of such musings was still upon me as I peered into the potting sheds and the stables, spied a strand of hair from a long-dead pony tucked into a rusty bolt and a discarded glove with the fingers worn through at the bottom of a broken plant pot. In one sense, the pony was still alive. So, too, the hand that wore the glove.

It was late. Time to go home. As I made my way down the yew walk and through the arboretum, back to my car, I was overwhelmed with sadness. It was hard to leave a place of such beauty, such peace, the scene of such deep and satisfying pondering.

Then I hit upon a plan. It was very simple. I would write a book, and for as long as I worked on it (twenty years) I would stay at Tyntesfield!

It would be a story about the effects of fatherlessness, told in the form of a tour, using a series of seemingly insignificant objects.

It would need a good narrator, one who sees things reasonably clearly (not too close, not too far away) and a cast of flawed but fundamentally lovable siblings, ready to be set adrift in the cold, cold waters of the twentieth century in tragically inadequate boats….

There would be a great deal of weeping, of course, as the house crumbles and the siblings are dispersed, as inevitably as dandelion seeds, as sadly as diamonds in a Romanov crown. There would be insatiable hungers and impossible longings…perhaps even a small amount of axe-wielding…but in the end, hopefully, love, because love is the strongest feeling, the one that lasts longest.

And so, I set about writing my debut novel The Infamous Gilberts. It was done alongside my day jobs (of which there were many), but inside my head, when anyone asked me what I did, I thought, “I am a writer.”

And inside my head, I didn’t live in my tiny cottage, I lived in Tyntesfield. I was born there and died there. I spent hours wandering up and down the attic stairs, getting up in the night to go to the loo, listening to the owls hooting in the wood, the foxes barking in the courtyard. I scooped up its sounds and its smells in a hundred empty jam jars and fastened the lids down tight, like the BFG with his dreams.

And I did my best to rescue the dust and the buttons and the drain hair. The tablet of coal tar soap may have long since disintegrated in some distant landfill, but it will live forever in the pages of The Infamous Gilberts. It is still in my heart. And now, perhaps, it is also in yours? Dear reader, remember, if you will, a little tablet of coal tar soap.

***