Gothic novels were my first love. I devoured Jane Eyre, Rebecca, Wuthering Heights, and everything else in a stack of novels bequeathed by a neighbor when they moved. After a few books I realized the similarity – and appeal – of the plots. The stories all featured an innocent young woman who arrives at a mysterious mansion, finds she’s in danger from some dark secret hidden in the mansion, then manages to solve the mystery and escape the danger. The crumbling castle or manor house is usually somewhere in Great Britain or Europe, preferably surrounded by gloomy moors, dark forests, and surly unhelpful villagers. Much later, I learned these were known as “Gothic novels.”

My books have always been historical fiction but I toyed on and off with the idea of writing something Gothic. Then while researching for another book, I saw photos of the pre-war mansions of Shanghai, and suddenly the prospect of writing a Gothic novel set in China became irresistible, if not inevitable. It was an opportunity to set a Gothic novel at the crossroads of East and West.

At the turn of the 20th century, Shanghai was “the Paris of the East,” a treaty port on territory the Qing emperors had ceded reluctantly to foreign powers. International banks, luxury hotels (and quite a number of seedy ones), consulates, shipping and railway offices joined warehouses and wharves to make the city a commercial powerhouse. Rich foreigners and Chinese built homes to show off their wealth and the architecture that proclaimed status was Western, not Chinese. Homes ranged from garden villas in the city to suburban estates of ten acres or more: houses boasting tennis courts, rose gardens, and stables for polo ponies. Grainy black-and-white images of Shanghai mansions that would’ve looked perfectly at home on a Scottish estate became a minor obsession as I worked through plots for a Gothic novel set in pre-war Old Shanghai. Of the many tropes in a Gothic novel, a mysterious mansion is at the top of the list and there were plenty of such homes to choose from.

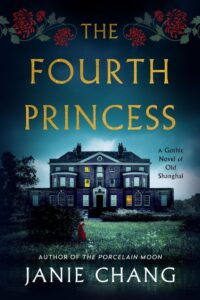

A photo of “Dennartt,” the mansion built in 1899 by barrister Vern Drummond, became the inspiration for fictional Lennox Manor, the house of secrets in my novel The Fourth Princess. A house like this, rendered moodier with signs of decay and eccentric features, made a plausible setting for secrets and past crimes. It would feature elements such as creaking floors and drafty rooms, voices in the night, and visions of a woman in red. Throw in a suicide and a missing bride. All augurs of danger.

However, as I began plotting, I realized something: the house was not enough.

Unless the story incorporated characters and situations that could exist only in 1911 Shanghai, there weren’t any good reasons for setting the story in China. It would be just another Gothic story dropped into Shanghai at the turn of the 20th century. To anchor the timeline, the plot had to be tied to historical events.

The first was the Wellington avalanche of 1910 in Washington State, in which 96 people died. It was the worst railway disaster in U.S. history. Out of this emerged one of the main characters, Caroline Vessey, an American who inherits not one but two fortunes as a result of the avalanche. She arrives in Shanghai eager for a new start with her new husband – who is a millionaire and therefore doesn’t need her money. But she hides secrets linked to the railway tragedy and it turns out that Shanghai is not the escape she’d hoped for.

The other historical event is the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, which ended in Beijing with the Siege of the International Legations. Lisan Liu, a young Chinese woman hired by Caroline as her secretary, finds life at Lennox Manor disturbing and not just because the house brings back childhood nightmares. At one of Caroline’s parties, she meets a Manchu princess who asks questions about her childhood – but it’s a past Lisan can’t remember.

The present day of the story is 1911. This is barely a year before the Emperor abdicates, a time of massive political transformation when China stands on the edge of change. Political intrigue permeates the atmosphere as businessmen and bureaucrats try to negotiate their way through the risks to come if and when China becomes a republic. Times of transition are fraught with conflict, and fiction thrives on conflict.

All of this would add specific historical background to the two main characters’ situations. Each of the women represents a slice of Shanghai society and not only do their back stories emerge from events unique to that timeline, but the secrets of their past resurface to haunt them in a Shanghai where political uncertainty adds to the peril. Bringing historical context into the story made it deserving of the time and place. There would be more just Gothic elements and the trope of a mysterious house.

Now there was more to the story than a spooky house. Mission accomplished?

Perhaps not. Partway through a first draft of The Fourth Princess – that thing which all authors dread happened – the story felt all wrong. It wasn’t Gothic-y enough. It read more like straight historical fiction. There followed hours of re-reading the draft, followed by ripping out large chunks of text. It had been too easy to get caught up in the history of the era. Historical novelists tend to be history geeks, and I had fallen into historical novel mode. I’d forgotten one of the first principles of Gothic – the danger must come from within the house. Yes, there are threats from the outside world, but the central plot must have the heroine unravel a deadly secret and escape the menace lurking in the house.

Some scorn “genre” fiction for being formulaic. But after The Fourth Princess, I understand the attraction of writing in a specific genre. It’s the challenge of doing something fresh within the constraints of the genre. It pushes an author’s creativity to honor tropes while also playing with them. With each nudge out of our comfort zone, we learn. And for Gothic, one lesson I’ve learned is that the house is not enough.

***