A wind gust strikes the window beside me, rattling the rain-streaked glass. Outside, a brief flash of lighting illuminates the slope of conifers that edge the hillside road. Abandoning my desk for a much-needed break, I lift my mug and swirl the shadowy liquid it contains, lingering over the last sip. Peering into the depths, it’s hard to not notice how the bitter leaves at the bottom resemble a crow with outstretched wings.

Maybe it’s the fierce weather. Maybe it’s the grim nature of the scene I’ve just finished drafting, but one cup of tea isn’t going to be enough this afternoon. I’m referring to true tea, of course: the slightly bitter leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant, not to be confused with the meek and insipid herbal tisanes so beloved by Hercule Poirot, Agatha Christie’s fussy detective.

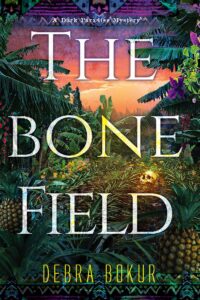

The less-than-sunny tale that unfolds in The Bone Field (the latest in my Dark Paradise Mystery series, set within Hawai’i’s tropical landscape) deserves the soundtrack of grumbling thunder outside the windows of my writing room—and the strong, dark brew that is my beverage of choice.

Though I’ve chosen an unlikely setting for my own mystery-crime series, a common scene in mystery novels—especially those of the cozy mystery subgenre—often includes a sleuth sipping tea as he or she contemplates the clues that have been strewn across their path; gathering them up to sort like so many jigsaw pieces as the lovely pot close at hand is slowly emptied of its contents.

As a reader, I crave a sinister backdrop, in the way that the tea tent at the village fête in Cover Her Face—the first Inspector Adam Dalgliesh novel by P.D. James—becomes an ominous set piece belying the deceptively peaceful day-to-day of English village life. I yearn for atmosphere, the kind created by this simple, bleak line from The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, which portends Holmes’ dark revelation of the vampire’s true identity and grim motive: “The tea is ready, Dolores,” said Ferguson.” What comes next, of course, is a wicked bit of business for everyone.

The true tale of this botanical beverage is a dark and twisted chronicle, featuring a simple plant that unwittingly became the foundation for the bloody building of empires; and was used as justification for the launching of wars while both nourishing and nurturing the growth of the opium trade.

Tea inciting war and drug trade, instead of soothing the victims of crime in peaceful villages? Well, yes, actually. Long consumed in China, tea (or cha, as it’s know there) was introduced to other parts of the world from its native growing regions by industrious Dutch merchants. The Dutch, French and Portuguese settlers who had begun new lives in what was then New Amsterdam (and became New York) were, themselves, voracious consumers of tea. The fragrant brew soon enchanted the colonists. By the 1640s, the leaves of the humble tea shrub had been elevated to a such a degree that they had found their way into the luxurious pantries of wealthy settlers who could afford such an exotic indulgence.

The East India Trading Company, founded by the British in 1600 and engaged in robust trading with regions of the Indian Ocean for spices, silks, and other commodities, recognized an opportunity and responded accordingly; ostensibly to bring tea to the masses, but more accurately to further ambitions of controlling the early incarnation of Britain’s presence in India, where large amounts of the tea supplied to other parts of the world—including the colonies along present-day Americas East Coast—were destined to be produced.

We all know what happened in 1773 when the British Parliament decided to intervene with a Tea Act designed to financially aid the floundering East India Company: Across the sea from Britain, enraged colonists in Massachusetts attempted to turn the whole of the Boston Harbor into a burbling cauldron of salty tea by pouring 342 chests of Camellia sinensis into the water’s depths to brew, unloved. The conflict continued to escalate, reaching a scalding point in April of 1775, when the first shots of the American Revolution were fired in Massachusetts.

Keen on monopolies, the East India Company had other problems to deal with. Foremost was its bid for control of India’s profitable opium trade. Though China was still producing the bulk of the world’s tea, consumed in a never-ending flow in Britain, it was not reciprocating with a corresponding purchase of British-produced goods. Enter India and the establishment of the first tea plantations in Assam, and a supply chain for vast amounts of opium. By 1839, war was raging between Britain and China’s Qing dynasty for control of trade, including tea and opium.

While my own preference is for tea with milk, unadorned by sweeteners, it turns out that sugar as a commodity was a diabolical game unto itself when connected to tea. In the early days of its expanding popularity in America, the beverage was given a boost by the introduction of sugar as a sweetening agent. This, in turn, fed the slave trade that supplied labor to sugar cane plantations in the Caribbean and America.

Sugar and opium aside, I do understand addiction. My life, you might say, has been steeped in tea consumption. Some of it has been delightful, such as a commission received years ago by Celestial Seasonings Tea Company to write original essays that appeared on ten separate flavors of the company’s bespoke tea blends, including their flagship flavor, Sleepytime.

Some has been less delightful. I’ve been drinking tea all my life—buckets of it, strongly brewed, bracing and restorative. Both my French-Portuguese mother and my father, who was an enduringly melancholy Russian artist, preferred tea to coffee, so it’s what I grew up drinking. To address my inconsolable wailing as an infant, my young mother, new to the game, was advised by her side of the family to fill my bottle with warm, milky tea. As family legend goes, it was the only thing capable of eliciting silence from me, and quickly became a staple in my diet.

I acknowledged the possibility of an actual tea addiction about a decade ago, when I was sent on assignment by the magazine I worked for to visit an Ayurvedic retreat center in Germany, located in the countryside some miles from the nearest village. The center was run by a team of esteemed physicians from India, and housed within a vast, sprawling estate with a manor house that I convinced myself must—by sheer virtue of its age—have been teeming with unsolved mysteries: lost keys and spectacles, the unexplained deaths of aunts and cats, faces appearing in mirrors when on one was around.

What I didn’t know was that for the duration of my five-day residency, I was not to be allowed anything containing caffeine. My first misgivings arose in my room, when I realized that the table holding the electric kettle also contained a small wooden chest filled with a selection of herbal teabags. Unaware of the misery of caffeine withdrawal that awaited, I shrugged off what seemed likely to be no more than an inconvenience, and went about the business of interviewing doctors and healers for my feature.

At the end of the second, caffeine-deprived day, I was beset by brutal muscle pain and a headache so massive and distracting that I couldn’t concentrate on anything. The head physician brought me a foul-tasting tincture tailored to my particular Ayurvedic dosha that he assured me would ease the throbbing pain in my head, but rejected my plea for a simple cup of tea. Convinced he was part of some larger plot, I planned my escape. That afternoon, while I was scheduled for a steam bath and a restorative walk through the landscaped gardens, I instead found my way through the tall, sculpted hedges to the paved road leading into the village and jogged off to hitch a ride into town.

By the time I arrived at the village’s single café, I’d plotted out an entire story that featured a well-meaning doctor as the primary victim in a gruesome murder. I downed a large pot of tea (and a slice of apple cake) and purchased a small tin of black tea to accompany me back to the estate. My takeaway from this experience was not that I should always eat to nourish my individual dosha, but that I should never leave home without my own stash of tea bags.

To this day, I carry a small supply in my day bag, prepared for those moments when I’m traveling and forced to negotiate with a bullying waiter for black tea with milk instead of some wretched hot water concoction involving lemon; or forced to explain to an unsympathetic waitress that coffee holds no appeal for me at all.

While I’m willing to concede that coffee has a pleasing scent, it has only crossed my lips three times in all the decades of my life, and is—at least in my estimation—gravely overrated. My detective, Kali Mahoe, drinks coffee grown on the plantations on the Big Island, but that choice was deliberate: All enduring characters, must, of course, be saddled with faults and flaws that give the reader a sense of their humanity. While Kali indulges in an occasional cup of tea, or iced fruit blends that are more akin to Poirot’s tiresome tisanes, she has yet to explore the blends now grown in Hawaii’s volcanic soils by artisan tea farmers. Perhaps those farms will feature in a future plot line.

Meanwhile, the insertion of tea to set a melancholy story tone is always a hook for me as a reader, as in the exchange in Gorky Park between Detective Arkady Renko and his lover-suspect Irina Asanova. Renko has discovered that live Russian sables are being raised for illegal export, and suspects that Irina is involved. The two are suspicious of one another, but they’re busy falling in love; the kind of love that’s rooted in obstacles and fear. To deal with these emotions, he offers her tea, of course:

Irina: What is it, Arkasha?

Arkady Renko: I have no sugar for your tea.

Irina Asanova: I don’t need it.

Arkady Renko: Do you still think I’m lying to you? That I am just a militia investigator?

Irina: Arkasha…

Arkady Renko: Do you imagine I’m trying to trap you, that this is all just a terrible game?

A terrible game, indeed: one accompanied by a hot, fragrant beverage with cruel links to the past, and often present at the scenes of fictional murders. Just as it should be. You’re welcome to disagree, but I won’t be listening. I’ll be in the kitchen with my book, measuring tea leaves and boiling water. And waiting for the kettle to click off, letting me know it’s time to pour.

***