When we worked together in the fundraising office of a third-rate law school in San Diego, my friend Melissa and I used to joke that we should write a sitcom about the uniquely terrible world of working for nonprofits. Imagine The Office, but instead of sales meetings and cute interoffice romances, all the chairs are slightly broken, no one can afford to pay their student loans, and—whoops—the billionaire donor whose name is on your youth center has just been accused of being a pedophile.

We rattled off a cast of characters based on our coworkers, came up with a few batshit storylines, but in the end we decided no network would go for it. A show about nonprofit work culture would be considered too niche. “There’s no market for that,” they’d say, and would probably be right. Still to this day, I wonder why.

The horrors of corporate culture and greed are so abundant in fiction today as to almost be cliché, and yet despite employing 10 percent of the US workforce, the nonprofit sector continues to fly under the radar in the stories we tell about work.

So often in popular fiction, nonprofits operate at the fringes of the narrative to tell us something about the characters who work for, volunteer for, and contribute to them. In Alice Feeney’s 2021 bestselling domestic thriller Rock Paper Scissors, protagonist Amelia’s low-wage job at the Battersea Dogs Home serves as its own kind of characterization. Flashbacks to her work with abused and abandoned dogs convey her selflessness, her bleeding heart, her lack of concern with material success, especially in comparison to her screenwriter husband’s naked ambition. Feeney uses the “charity worker” stereotype to convince the reader of Amelia’s inherent goodness, only to later upend it.

“Just because Amelia works for an animal charity,” one character tells us, “it doesn’t make her a saint.”

Even many novels set squarely at nonprofit educational and cultural institutions are rarely interested in, or viewed as being part of, the 501(c)(3) industrial complex. Literary novels set on college and university campuses, like Julia May Jonas’s Vladimir, often focus their commentary on academia as a self-contained institution. Meanwhile, mysteries such as Katy Hays’ The Cloisters and Peng Shepard’s The Cartographers, which take place at the Met Cloisters and the New York Public Library, respectively, largely eschew the mundanities of nonprofit culture for the escapist fantasy such institutions inspire—the academic, the arcane, sometimes even the magical. The dark academia genre has never been more popular, and yet the true character of not-for-profit institutions has never been less understood.

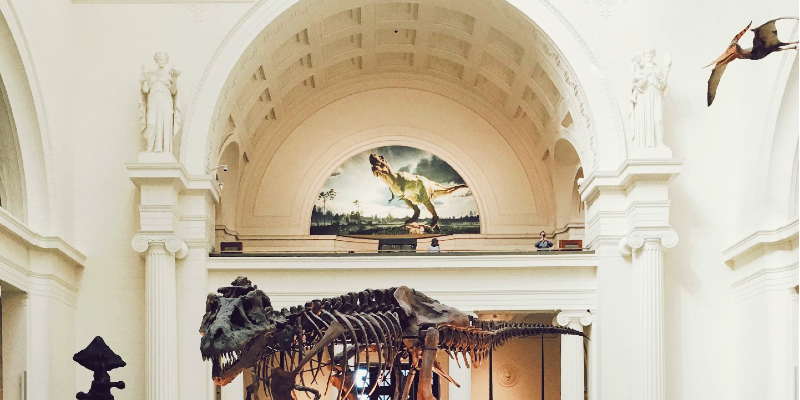

When I set out to write my second novel, The Paleontologist, it wasn’t my intention to illuminate—or much less, satirize—the sector in which I’d worked as a fundraiser for more than a decade. I was there to pay homage to Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park with an atmospheric, dinosaur-filled twist on a ghost story. But like my protagonist, Simon, who starts the novel having accepted a job at the natural history museum where his sister disappeared decades earlier, I found it impossible to navigate the world of the Hawthorne Museum without becoming entangled in the politics of austerity and privilege that have defined my working experience.

*

My first experience in the nonprofit sector was as an unpaid summer intern at a social service organization in Tucson, Arizona, writing grants for case management and homeless support. An undergrad in English literature, I landed there after failing to be admitted to any of the fancy New York publishing internships I’d applied to. My mom had worked for the organization herself and helped get me in. I would later come to learn that the path to a career in “development” (nonprofit jargon for fundraising) is often accidental.

What struck me early on in my internship was the focus on revenue and growth, on bringing in enough money not just to keep the lights on, but to meet a moving, often arbitrary fundraising target. Every organization seemed to want the same thing: to balloon their budget, expand to new sites, reach ever more people with an ever lengthening list of programs and services—whether the community needed it or not.

We often think of nonprofits as being set apart from the greed of the corporate world, but in many cases they are just as much part of the capitalist machine as their for-profit counterparts, and equally beholden to the “grow or die” mindset many corporations use to justify prioritizing profits over people. The difference is that in the nonprofit world, the end goal isn’t to line shareholders’ pockets. We in the third sector like to think we’re above that, called to a higher purpose: to serve our organizations’ “missions” and expand their “impact.” And if that means we have to keep our employees at poverty wages, working long hours in ugly, barely air-conditioned offices with outdated technology and criminal benefits, then so be it.

We may not prioritize profits over people, but all too often we prioritize the people we serve over the people we employ to serve them.

*

Some ten years after that eye-opening internship, as I set out to craft the fictional museum setting of The Paleontologist, I was attracted to the idea of exploring the Gothic through an authentic nonprofit lens.

What I landed on was a natural history museum of no particular importance or esteem, hemorrhaging money and cannibalizing its endowment after being closed for months during the Covid-19 pandemic. The crumbling building and neglected interior heightened the spooky atmosphere of the novel, while also illustrating the kind of selective austerity found at many nonprofit workplaces of a certain size.

At the Hawthorne, there’s no money to fix or replace what is broken or inadequate. Budgets have been slashed, positions consolidated, and benefits downgraded to save on costs. The threat of institutional collapse looms large. Yet when it comes to its executives’ six-figure salaries and the expensive consultants they retain to do their jobs for them, the budget is never too tight.

At the beginning of the novel, Simon arrives at the doors of the museum, dismayed by its shambling state when the institution is paying him more than he could easily refuse, despite having good reason to stay far away. And so begins the complicated push-and-pull of guilt and entitlement that he—a gay white man from a deprived background—wrestles with throughout the novel, and which I have had to grapple with too.

*

Like Simon, I’ve done okay for myself in the nonprofit sector. Moving swiftly from organization to organization, promotion to promotion, I more than doubled my salary in the first few years and have continued to advance since then. Also like Simon, I would like to think that’s based on a track record of results and exceeding fundraising goals—but as a straight-passing white man, it’s hard to feel completely at ease in that assumption.

The nonprofit sector is no more immune to gender and pay inequity than the corporate world. Across the US, 73 percent of nonprofit workers are female, yet only 21 percent of the largest organizations are led by a female CEO. A 2021 compensation report published by GuideStar, a leading nonprofit information service, stated that women CEOs of nonprofits were paid 8 percent less than their male counterparts. For Black and Hispanic/Latina nonprofit workers, the pay gap is likely even greater.

As with many lower- and middle-class white men, privilege has been a thorny issue for me. This was especially true throughout my undergraduate years. Compared to my well-heeled classmates at the University of Chicago, where I received a need-based scholarship, it was easy to feel I stood on the underprivileged side of the social spectrum. I carried—still carry—tens of thousands of dollars in student loans. I couldn’t afford to fly home for Thanksgiving. Instead of a shiny white Macbook, I made do with a crappy Dell that broke every semester like clockwork.

Freshman year, I joined the university newspaper and learned that one of my fellow columnists was the son of a jaw-droppingly famous literary novelist. That same year, this columnist and his friend—also in our year, also the son of a best-selling author—sold their first book to Penguin. I was bitterly jealous, not least because my novel, scribbled in my spare time outside my full-time summer job as a camp counselor, had been passed up by every agent I’d sent it to. All I had ever wanted was to be a published author, but it seemed the cards were stacked against me.

The experience had lingering effects, coloring my self-view and making it harder for me to see myself in the privileged light society had shone on me as a white man, the proverbial ruling class. If I were really privileged, I would have been published by the time I was nineteen. If I were really privileged, I would have been interning at Random House or Esquire like the other English majors in my year. If I were really privileged, I wouldn’t be working in the nonprofit sector at all, but would have been making six figures in corporate communications for some soul-sucking Fortune 500 company.

It had never struck me as a particular privilege to be the son of a single mother who had supported her three children on a $42,000 income as a nonprofit grant writer. And yet, I found myself thinking while drafting the novel, if my mom had never worked for the Red Cross, would I have been invited to intern there? Without that experience, would the third-rate law school have hired me, enabling me to grow my skills? Where would I be today had I not benefited from that personal connection? And were I not a white man, would I have been so emboldened to constantly strive for new roles, promotions, and raises, and then gotten them?

Just the fact that I was having a second novel published was evidence of the privilege I had tried to deny. The literary agent I eventually signed with was a friend from grad school at the University of Edinburgh, a stroke of luck that never would have come to me had I not been lucky enough to swan off to Scotland for a year in my early twenties (even if I am still paying for it).

From the very first pages of The Paleontologist, I found my own injustices, anxieties, and blind spots seeping into Simon and the world he inhabited. A world, in many ways, I felt I already knew.

The Hawthorne Museum of Natural History is an institution haunted by specters—perhaps none more insidious than its culture of nepotism, prejudice, and the uncanny ability of white men of no particular merit to get ahead. An institution in which Simon must not only find the truth of what happened to his missing sister, but reconcile his disadvantaged upbringing with the privileges he now enjoys.

Writing this book has been a gift. Not only did it allow me to shed light on the underrepresented nonprofit sector—a sector that, for all its flaws, I love and champion as a force for good in a society that has never needed it more—but it also allowed me to shed light on myself.

Still, I think that sitcom would be hysterical.

*