Graham Greene met Dorothy Glover in London in the spring of 1939 on the even of World War Two. Glover was working as a theatre costume designer in the West End. Greene, having just finished Brighton Rock and struggling to write two novels he’d accepted advances for—The Confidential Agent and The Power and the Glory—felt unable to work at his family home due to his rocky marriage and noisy three-year-old son. So he rented a writing studio from Glover in Bloomsbury’s Mecklenburg Square, where Glover lived with her mother. Shortly afterwards Greene and Glover began an affair.

After Britain declared war on Germany the two began openly cohabiting while Greene’s wife Vivien, and their two young children, were living in the Sussex countryside. During the Blitz, Glover and Greene both worked as neighbourhood Fire Watchers in Bloomsbury. Glover also worked as an illustrator and writer under the pseudonym Dorothy Craigie. With Greene writing and Craigie illustrating, the pair published four children’s picture books together, though initially Greene’s name was omitted from the covers. They also began to spend their free time trawling London’s then numerous second-hand book stores and stalls seeking out Victorian detective fiction novels. They were to amass an enormous collection of crime novels. Amid the war debris of London they commenced a joint hobby that would ultimately outlast their romantic relationship, which fizzled out after the end of the war as Greene began yet another affair, this time with the wealthy American wife of a Member of Parliament, Catherine Walston, described in his 1951 novel The End of the Affair (though there are elements of his relationship with Glover in that novel too).

And so in 1962 Greene and Glover, who managed to stay on good terms and still swapping and collecting Victorian detective fiction, decided to issue a catalogue of their joint collection in a limited edition of just five hundred copies published by The Bodley Head. The book, simply entitled Victorian Detective Fiction, eventually became available in 1966 and featured a preface by Greene, an introduction by the bibliophile John Carter, and was bibliographically arranged by Eric Osborne—both Carter and Osborne were friends of Greene’s and Victorian book specialists at Sotheby’s Auction House. Each copy was individually numbered and signed by Greene, Glover, and Carter. Greene hoped that the bibliography of approximately five hundred books would be a useful aid to both second-hand and antiquarian book dealers, as well as crime fiction lovers. It is indeed a comprehensive list of Victorian crime fiction. But how did Greene and Glover, engaged in their affair amidst Blitz-torn London, come to their mutual love of early crime novels and amass the collection?

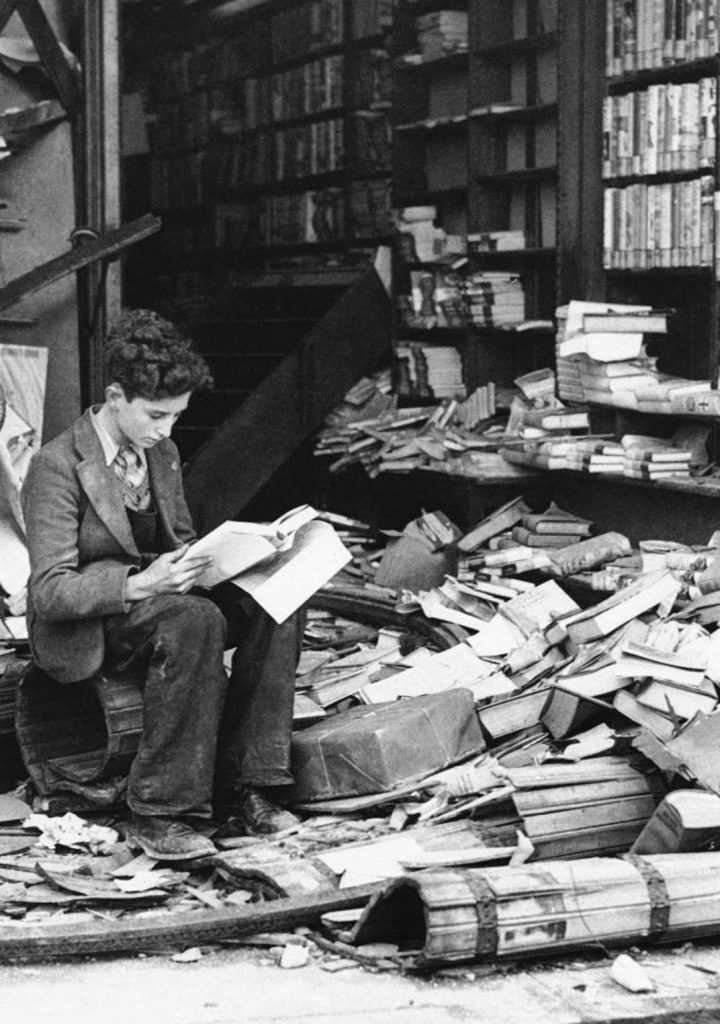

Greene claims that their shared interest in Victorian writing and a desire to build a collection came during the war, where he spent most evenings at Glover’s small flat on Bloomsbury’s Gower Mews. The couple had spent an evening rereading Wilkie Collins’s 1868 novel The Moonstone. They began to think about the origins of the detective story and who, before Collins and Poe, may have been writing detective fiction. They decided to try and build a collection of detective fiction written and published in the Victorian-era from the cheap shelves of London’s used bookstores. The British capital was home to numerous second-hand bookstores in the 1930s. Paper rationing during the war meant new titles were few and far between and so hungry and deprived readers especially sought out used books to feed their literary habits. Living in Bloomsbury, London’s literary centre, and working at nights watching for fires during the Blitz, the couple were largely free to roam the city’s book districts during the day.

Greene recalls that they began their hunting amid the second hand books shelves at Foyles, the enormous bookstore that once occupied the whole building on the corner of Charing Cross Road and Manette Street, which ran back into Soho (the building was demolished in 2017). From there they widened their explorations up and down the Charing Cross Road, then, as now, a centre of the used book trade. From there they ventured to the numerous bookshops of Bloomsbury, Soho, Mayfair, and the book stalls that once lined Farringdon Road. Some stores that yielded finds were well known, such as Heywood Hill on Mayfair’s Curzon Street, where Nancy Mitford worked during the war.

Searching for books in the Blitz, Greene and Glover would sometimes set out for a bookshop they hoped would yield treasure for their collection only to find it destroyed in an air raid overnight.Others were distinctly shabbier and are now long forgotten, though in Keep the Aspidistra Flying, George Orwell’s great novel of thwarted ambition in the 1930s depression, we have a fantastic description of just such as a store, McKechnie’s, based on Orwell’s own time working at the Booklovers’ Corner, a second-hand bookshop in London second great literary cluster, Hampstead. Searching for books in the Blitz, Greene and Glover would sometimes set out for a bookshop they hoped would yield treasure for their collection only to find it destroyed in an air raid overnight. Another good source was the furniture and bric-a-brac stores that sprung up in London selling off bomb damaged goods, including boxes of random books.

Their collecting continued into the post-war years, and after their nine year sexual relationship ended. At some point Graham’s younger brother Hugh, an executive at the BBC, joined them in their book hunting forays. Greene recalled that by this point he and Glover had, ‘…developed a nose for the kind of titles in Victorian times which hid a detective interest.’ They developed a particular fondness for Sherlock Holmes parodies and, so Greene maintained, never lost their original passion for Wilkie Collins.

How to summarise the Greene-Glover collection? It is exclusively nineteenth century and concentrates on the predecessors of Sherlock Holmes. Greene and Glover were ruthless in their chronological demarcations so that, despite their deep appreciation of Conan Doyle, The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902), and other Holmes classics, are excluded as twentieth century, and so therefore not strictly Victorian. They were not overly fussy as to condition—ex-library stock as well as the very early cheap paperbacks from railway bookstalls were collected, as well as many first editions. Early Victorian titles were often not specifically marketed as detective fiction though still met Greene and Glover’s basic collecting criteria—that they, ‘…be mainly or largely occupied with detection and should contain a proper detective, whether amateur or professional.’

It was a global collection with the greats of the early English detective novel alongside French roman-policiers of the 1850s/1860s, early Americans such as Poe, and Australians, notably Fergus Hume (both were particularly fans of Hume’s 1886 The Mystery of a Hansome Cab set in Melbourne). The only title the bibliographer John Carter questioned was Jules Verne’s Around the Wold in 80 Days (1873). Greene and Glover argued that a major sub-plot concerns Scotland Yard’s Detective Inspector Fix, who mistakes Phileas Fogg for a criminal who has robbed the Bank of England, chases, and arrests him.

Chronologically the collection divided up between 1846-1870, or from Poe to Dickens’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood; 1871-1890, referred to as the period of the “Sherlock Holmes Revolution”; and 1891 to Queen Victoria’s death in 1901, when more than twice as many detective novels were published as in all the previous forty-five years. Within these decades are many well-known authors—Conan Doyle, B.L. Farjeon, Emile Gaboriau, Sheridan Le Fanu, and Hume, as well as what Greene and Glover called “near-detective fiction” by writers such as Wilkie Collins. Lastly there were, ‘…writers nobody but the detective fiction aficionado has ever heard of at all.’ Greene and Glover liked to distinguish between the professional detectives—Collins’s Sergeant Cuff, Gaboriau’s Monsieur Lecoq, or the Pinkerton operatives of America—and the amateurs—Conan Doyle’s Holmes, Poe’s Auguste Dupin and M.P. Shiel’s Prince Zaleski.

Ultimately it was Greene’s reputation and fame that brought the collection to the book trade’s attention and encouraged The Bodley Head to catalogue it. However, Greene himself admitted that it was Glover’s voracious consumption of detective fiction that really built the collection. When Anthony Hobson, the legendary bibliophile, partner at Sotheby’s, and head of their Book Department (at just 27!), referred to the collection as being Greene’s, he was swiftly corrected by the author who insisted the collection really belonged to Glover.

And so Greene and Glover’s Victorian Detective Fiction remains perhaps the ultimate reading list for fans of the genre and the period. It begins with Arthur à Beckett’s 1870 novel Fallen Among Thieves, an early Victorian country house murder featuring the private detective John Barman, and ends with Edmund Yates’s 1875 novel A Silent Witness featuring a medical detective called Clement Burton. In between are around five hundred novels, alongside detective memoirs and autobiographies, as well as magazine and literary journal serialisations of detective stories from the period. Just about every book the Victorian crime fiction lover could ever want basically.

Dorothy Glover died in 1971, unmarried and still living with her widowed mother, after which Greene and Glover’s jointly produced children’s book were reissued under both their names for the first time. Greene dedicated The Confidential Agent to her while some critics believe the character of the poor shipwrecked Helen in Greene’s Sierra Leone-set semi-autobiographical novel The Heart of the Matter is composed of elements of Glover. Greene died in 1991.

Of course an incredible collection of so much detective fiction should have a little mystery about it. In 1966 Greene wrote that he expected that the collection might double in size over the next decade. Whether it did or not, and what happened to the collection, is unclear. As best as I can tell it was housed with Glover at her home in the village of Crowborough, East Sussex. What then happened to the books when Glover died in 1971? It seems most likely the collection was sold off to local second-hand book dealers. I am sorry to report that I can find no trace of this once great trove of Victorian detective fiction. A final mystery endures.