Some years ago, I was working on a draft of my first real mystery thriller. In the opening pages, I included a bit of description meant to establish the location of the story (my hometown, Gainesville) and the time of year (late spring, the most miserable season in Central Florida). When I submitted the chapter to a writing workshop, one of the more experienced writers in the group immediately commented: “You need to cut all this setting stuff. Thriller fans don’t care about setting. They want to get to the action, quick.”

Like most writers, I passionately despise criticism of any kind, but this rankled more than most. It rankled, of course, because I knew that the writer who had made this comment (a very elegant and smart older lady with a couple of published novels under her belt) was partially right. Not about the “thriller readers don’t want to read about setting” part (I totally disagreed with that portion of her response; my disagreement is, in fact, the topic of this essay), but with the fact that I was rendering my novel’s setting improperly. That is, I was describing the setting in a very lazy and arbitrary manner, disconnected from what was actually happening in my main character’s mind or, for that matter, in the plot.

I would bet that a lot of famous writers have suffered a similar reaction about their use of setting from an editor or critique partner. Perhaps this is why so many otherwise fine novels—and especially mystery and crime novels—have very little sense of place at all. This is true even of crime novels whose main point of attraction is their dark, exotic, or romantic locale. How many mystery novels are set in Key West? Or New York City? Or the Rocky Mountains? It’s almost as if the writers of such novels believe that the setting, having been established in the reader’s mind when they first pick up the book and read the jacket copy (“a chilling tale of murder on the mean streets of South Chicago”—got it) will do the hard work themselves of imagining the world in which the story is set.

In short, setting is treated as a given.

It doesn’t have to be this way, though. Setting is, I believe, a great and underused tool for crime novelists to find their way into the essence of their stories, and the consciousness of their characters. Take this passage from the opening of Ross Macdonald’s novel The Moving Target, in which the hero, P.I. Lew Archer, is being driven to a beach town where his next client resides.

The scrub oak gave place to ordered palms and Monterey cypress hedges. I caught glimpses of lawns effervescent with sprinklers, deep white porches, roofs of red tile and green copper. A Rolls with a doll at the wheel went by us like a gust of wind, and I felt unreal. The light-blue haze in the lower canyon was like a thin smoke from slowly burning money. Even the sea looked precious through it, a solid wedge held in the canyon’s mouth, bright blue and polished like a stone. Private property: color guaranteed fast; will not shrink egos. I had never seen the Pacific look so small.

Instead of slowing down Macdonald’s narrative (as the lady in my workshop might have expected), this bit of descriptive prose actually accelerates it. The setting draws the reader in because it creates suspense and intrigue. Why is the protagonist (the nominal “tough guy” of this hard-boiled mystery) so uneasy at the sight of this canyon town? Why does he feel “unreal”?

If one reads this passage closely, one realizes that Macdonald has seeded it with what writer and editor Sol Stein calls “omens,” portents of things to come. Specifically, Macdonald evokes an almost palpable sense of menace. Even the sea itself—usually a symbol of vast space and power—is diminished, occluded, a “wedge held in the canyon’s mouth.” The canyon, Archer senses, is a place of ravenous greed and hidden violence. And by his contemptuous and wry reaction, Archer reveals much about his own character, that of a fundamentally honest and decent man caught in an environment of moral corruption. No wonder he feels “unreal.” He has just stepped into a dangerous realm where good and evil blend together, in ways that promise to be surprising and profound.

Of course, Archer is venturing to a new place, which is a great excuse for the writer to expend some time and energy describing the setting. But a similar effect can be achieved even when the character observes an environment that is familiar to him—so long as that familiarity is, itself, an entry-point into their mindset. Here is a paragraph from the first chapter of Charles Willeford’s classic crime thriller, Sideswipe, in which the protagonist, Hoke Moseley, is resting for a moment on his back patio.

The sun porch had open, jalousied windows on three sides, and a hot, damp breeze blew through them from the lake. The Florida room faced a square lake of green milk that had once been a gravel quarry. The backs of all the houses were toward the lake in this Miami subdivision called Green Lakes. Not all of the home owners, or renters, had glassed-in porches like Hoke. Some of them had redwood decks in back; others had settled for do-it-yourself concrete patios and barbeque pits; yet all of the houses in Green Lakes had been constructed originally from the same set of blueprints. Except for the different colors they had been painted, and repainted, and the addition of a few carports, there was little discernible difference among them.

Article continues after advertisement

I love this passage not only for its sharp-yet-graceful writing, but also for the way it undercuts any romantic visions of Miami that the reader might hold. Instead of windswept beaches and palm trees, we get Green Lakes. Could anything be uglier than a “green lake”? Not just a green lake, but a “lake of green milk.” Blech! It is a neighborhood of cookie-cutter houses that have evolved and individuated in a multitude of unique but generally hideous ways. What could possibly make this milieu even worse? Perhaps the introduction of a demented psychopath or two (which Willeford’s plot will soon provide).

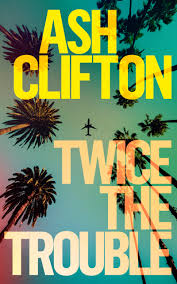

Placing a mystery into a setting with exotic or romantic connotations, and then cutting against those very connotations, is a technique employed by many fine crime writers. Even I, in my own humble way, try for something similar in my novel, Twice the Trouble, which is set in a place that many people think they know: Orlando, Florida, land of Mickey Mouse and amusement parks, but also of shady businesses and drug-related crime.

But perhaps the ultimate reason to strive for a vivid setting in a crime novel is that a great setting particularizes the story. A detailed and unexpected sense of place can make a mystery narrative—which, let’s face it, is always somewhat of a farfetched proposition—more real.

And realism, after all, is what we’re striving for, right?

***