For years, I tried to find a book that would impress my grandmother, one of the most voracious readers I’ve ever known. Nothing would stick with her, especially considering she said that our wants in literature were opposed by nature: she was old, and tired of reading for anything other than pleasure—whereas I was young, and apparently would read anything. The first book I convinced her to read that she actually thanked me for—and my grandmother doesn’t say thank you a lot—was Turning Angelby Greg Iles. While it’s technically the second book in his critically acclaimed Penn Cage series, this is also one of his best books, something that a much younger version of myself flew through despite the length and complex nature of the mystery. And, perhaps, I can largely credit Greg Iles with being one of the first writers to convince me not only that I could write crime fiction, but that I might actually have a yearning to do so.

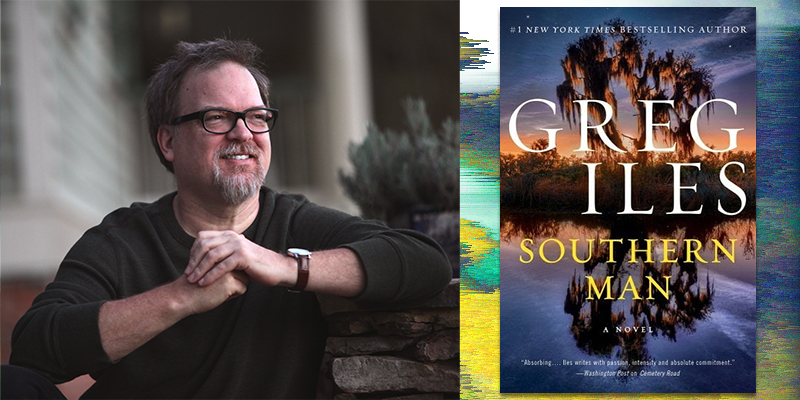

Iles, born in Germany, relocated with his family at a young age to Natchez, Mississippi, a setting which would later inform many of his greatest novels. He is the author of nineteen novels, many of which have gone on to be mega-bestsellers, influencing a whole new generation of mystery-thriller writers like myself who find his prose addicting, powerful, and absorbing. Iles isn’t afraid to talk about serious topics, often involving his characters as a medium for readers to engage in dialogues about things like racism, sexism, and other forms of hatred, as well as the existence of hate groups and how they shape and inform the world we live in.

Even when enduring the most serious of physical maladies, he has never ceased to write for his fans, putting out a whole new trilogy of Penn Cage books after one particularly harrowing medical event and writing throughout the recovery process, showing that books can truly heal and transform readers into better, more responsible, and more intelligent people. His new opus—what is likely the final Penn Cage book ever—deals with so many different struggles Americans are facing as they turn against one another based on ideology, politics, and real and imagined histories of the areas we occupy in the United States. Southern Man is perhaps Iles at his most profound, his most epic, and his most assured as he wipes the dust off the story of Penn Cage one final time, if for no other reason than to please his readers by giving them the ending they long for, and going out in true Ilesian fashion.

Matthew Turbeville: Mr. Iles, first of all, it’s one of the biggest honors of my life to be able to interview you. I honestly never dreamed this day would come. When I was fifteen, I (at random) picked your novel Turning Angel from a display in a local bookstore. At the time, I thought I was a horror author. Your work changed my mind, and introduced me to a world of mysteries, thrillers, and cross-genre novels which blew my mind. I later gave my copy of Turning Angel to my grandmother, a woman who is notoriously hard to impress, and to my surprise (because, again, she’s picky), you became her very favorite author. To use the cliché in the most sincere way possible: this feels like a dream.

Since then, you’ve gone on to write nearly half a dozen more Penn Cage novels. I’m always intrigued when an author can (successfully, entertainingly, brilliantly) continue a series with the same primary protagonist for so long. What drew you in about Penn Cage, and how were you able to keep peeling back the layers of these characters to produce novel after novel?

Greg Iles: First of all, it’s great to be interviewed by someone so familiar with my work. That’s a rarity in this time, for almost any writer. So… perhaps Penn Cage has turned out to be such a long-lived character because I never set out to write a series based on him. The Quiet Game was written as a standalone, and seven years passed before Penn and his family called to me again. Now I’ve done something that very few series authors ever do, which is to age my protagonist literally on the page, leaping fifteen years ahead of the Natchez Burning trilogy to drop a fully aged and frighteningly mortal Penn Cage into 2024 in the midst of this insanely dangerous election year.

Greg Iles: First of all, it’s great to be interviewed by someone so familiar with my work. That’s a rarity in this time, for almost any writer. So… perhaps Penn Cage has turned out to be such a long-lived character because I never set out to write a series based on him. The Quiet Game was written as a standalone, and seven years passed before Penn and his family called to me again. Now I’ve done something that very few series authors ever do, which is to age my protagonist literally on the page, leaping fifteen years ahead of the Natchez Burning trilogy to drop a fully aged and frighteningly mortal Penn Cage into 2024 in the midst of this insanely dangerous election year.

MT: You admit that like yourself, Penn Cage is, in your latest novel, Southern Man, suffering from multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer you were diagnosed with at a much younger age. I’m curious what it’s like to know, in one sense of another, your possible fate, which seems eerie and devastating in itself, and also how it feels produce (in my opinion) phenomenal novels during these years between when you learn that you have a certain disease, and when the disease worsens with a chance to take your life. What were your expectations of yourself and your writing during this time? Did you ever fear that you wouldn’t say everything you needed to say (and do you feel you have more stories undone, more novels left to write)?

GI: This a secret I kept since the age of 36, when myeloma was a very brief death sentence. It had just killed Sam Walton when I was diagnosed, and back in those days, people lost careers over simply having a serious cancer. I was lucky enough to turn out to be in the one percent of myeloma patients who lived more than twenty years with the frank disease without lethal progression—though of course I did not know that as I lived those years. I lived each day knowing I could be sliding into death at any time. Then, about three years ago, I nearly died without knowing that my cancer had “switched on.” By this time, my mother had been diagnosed with the same cancer, and I’d had had to watch her die of it in front of me, while I was writing this novel. I don’t think I could have written Southern Man without incorporating all that into the story. Anyway, I made a choice to finish my book before getting the bone marrow transplant I needed—work that I thought would take me about eight weeks. Instead, finishing Southern Man took more than two years, while I was enduring what they call “double chemo.” That choice probably cost me some years of life on the back end, which could be sooner than I want. But I’ll be getting stem-cell transplant soon after after publication, if certain factors go my way. But—I digress. Back to books.

MT: It’s hard to express the way you captivated me as a young reader when I was so engrossed with Turning Angel. I remember where I was, and what I was doing: I was at a mock trial event in Horry County, South Carolina, where I was supposed to play a liar, a cheat, and a thief in the pretend courtroom. I’m naturally a truth-teller and a friendly person, so needless to say, it didn’t work out for me. And instead of falling into the mind of this person I was supposed to play, I instead fell into the mind of Penn Cage.

In other words, what is your advice to young writers, new writers, old writers, and struggling writers alike, who want to create a world as real as that which you created through Penn Cage’s eyes? How do you capture a reader so wholly and maintain that hold on them?

GI: I happen to be in that camp that believes the ability to write is inborn, or the closest thing to it. My friend and bandmate Scott Turow and I disagree about this. I do concede that you can teach someone to be a better writer. But that essential gift, the ability to do the things you just asked me about—particularly the instinctive ability to handle time on the page, for example—are things that you have to simply know. As an example, I often say, “I could write a novella set during World War Two that covers all of 1939-1945. Or I could write a thousand-page novel that takes you from inside a landing craft approaching Normandy Beach to the top of the cliff on D-Day–FINIS. Think of all the various ways to deal with time between those two extremes. My advice to writers… read all you can. Read the people who do it best, and read the books that move you again and again. The best ones will reveal new jewels every time you do. Every time. You’ve got to figure out why. You’ve got to figure out the magic trick being performed right in front of you: turning linearly printed ink into life. That’s how you master the craft. But the craft isn’t the root of it. You are the root of it. In the end you are your own subject, no matter what story you think you’re telling. That’s how you make others feel that what you write about is real. They’re living a second life through you. Give them that gift to the best of your ability. If you do it well… there’s no limit to where you can take people.

In the end you are your own subject, no matter what story you think you’re telling.MT: Cage is a virtuous man. He has his own problems, and he’s conflicted in his own ways, but overall he fights for what he believes is right, and stands by the people he believes in, and struggles to maintain his beliefs in how the world is—the good, the bad, and the ugly—with a sense of hope to him too, despite everything he’s been through (and, spoiler, he’s been through a lot). How much of this is you? How difficult is it to construct a character out of thin air, making them flesh and bone, and especially in the case of Penn Cage, how close is he to home, and why do you continue to return to him, book after book?

GI: As the cliché says, “The line between good and evil runs right down the middle of every human heart.” We all struggle between light and darkness from the time we’re children. It’s the two-wolves thing. Or Karl Jung’s Shadow. We must create ourselves even as others try to shape us. We must recognize and deal with all that we find within ourselves—some of which can be a pretty harrowing surprise. Penn is like me in that he has that crusading impulse to confront and right injustice, but he’s as flawed as most anybody else. He particularly struggles with the realization that to fight antagonists of great power, one is almost always driven to embrace the tactics of one’s enemy. Penn carries the knowledge that he has done that many times, and that’s quite a weight in someone who tries to be a moral person, at least to the extent that he can be. That burden, yet his willingness to act for ultimate justice under the weight of it—even to break the law to achieve that justice—makes him a very effective and realistic protagonist.

MT: You returned to Cage initially with Natchez Burning and the two other novels which followed in a new trilogy several years ago. You wrote these during a particularly difficult time where your health was concerned. Megan Abbott once quoted Shirley Jackson to me, something along the lines of “If you write it away every day, nothing can ever truly get to you.” Do you believe this is true? Is that why you persevered in your own writing, or is there another reason?

GI: I don’t really believe what Jackson said there. When you’re fighting what’s officially classified as an incurable cancer, you’re facing a black door every day you wake up. There’s no magic—not writing or even music—that can blind you to that reality for long. I wrote about that in Southern Man, of course. Denial is a powerful defense mechanism, and I got to be a master at it for a while. But I also found that the only way to avoid thinking about something so final is to focus on serious stressors even closer to you—at least as far as you know. For example, in 2001 I was in a car accident in which I lost my right leg below the knee and had my aorta torn, as well as breaking too many bones to count. The X-rays even missed a couple. Everyone I knew was horrified, and clearly that accident nearly killed me. But I was strangely tranquil through it all. Because I knew that the myeloma I secretly carried could kill me much more easily or surely than that pickup truck nearly did—even with the torn aorta. It’s a strange way to live, especially when almost no one else knows what you’re dealing with. The hawk of mortality hovered above me everywhere I went, and I always felt its shadow. It nested on my roof like the Grim Reaper while I slept—and still does. Now, at least, I’m fighting him in the open.

MT: Out of curiosity, who are the authors working today and the books written recently you recommend full-heartedly, both in the crime/thriller/mystery genres, but also in any genre you love? What books did you read and enjoy most during your formative years, and do you have any opinions on what children (our future authors) read (as well as how they read) today, and what literature may look like many years from now in the future?

GI: One surprise I got from getting to know Scott Turow is that both of us were strongly affected very young by Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo. I think America might be a different place if every boy who loved that book had been taught that it was written by a man who was mixed-race, his grandmother being an enslaved Black woman from Haiti. And Dumas, though light-skinned, faced racism all his life.

As for what children should read? The more the better, I say. My first literary agent, a wonderful woman, believed that the first book that really resonates with any child has a lot to say about that individual’s later personality. For me it was Faith McNulty’s Arty the Smarty, and boy was she right.

you can learn almost everything you’ll ever need to know about writing by reading Lonesome Dove or All the King’s Men.I don’t want to say much about writers working today, because I’ll leave out too many. I will say this: you can learn almost everything you’ll ever need to know about writing by reading Lonesome Dove or All the King’s Men. I would also add this: I was a great admirer of Peter Straub, the author of Ghost Story, who died nearly two years ago. Most people know of Straub through The Talisman, which he co-wrote with Stephen King. But Straub’s Blue Rose trilogy—comprised of Koko, Mystery, and The Throat—is inarguably some of the finest crime and psychological writing of the past fifty or sixty years. The gift that man had within him… my God. He once said there were a couple of times he had to turn away from certain things inside himself, because he couldn’t stand the result of his perception aimed so directly and deeply inward. I never met Straub in person, but he said some very nice things about my books in the last year of his life, and we corresponded a little. He even invited me to visit him at his house, which sadly, I never got to do. But I’ll tell you this: nothing in this industry—not being number one on the Times list, or getting a movie made, nothing—compares with getting genuine, private praise from a writer you’ve deeply admired for most of your life. That’s what writing is about for me. Moving people. And when you move someone who has moved you as deeply as anyone ever has, well… you finally feel like you’ve done something valid.

As for what literature might look like in the future… I probably won’t be here to see it, so I’m not too concerned about that. My oldest son has some talent in the writing vein, so I’ll let him deal with the AI that’s barreling toward us like a herd of runaway semi-trucks. Semi-trucks carrying supercomputers, I should say. Although AI can do the job on an iPhone almost as well, it seems.

MT: Another book I loved by you was Blood Memory, a novel about Cat Ferry, who specializes in things like bite marks when solving crimes. The novel becomes a riveting mystery and also something very personal for Cat as the story progresses—when you write characters outside of yourself (different races, sexes, sexualities, etc.), whether from their direct viewpoints or not, what do you keep in mind with crafting these characters? What responsibility do you hold toward readers when you think of representation, especially the characters often overlooked in small Southern towns?

GI: Writing cross-gender narration—especially in first person—is one of the toughest challenges there is. Writing cross-racial narration is even more of a minefield, at least during this present time of hyper-examination of all narrative text written outside whatever someone was born as—man or woman, white or Black, European or indigenous, gay or straight. The solution to this dilemma—if well-executed by a gifted author—is to write from the essential humanity of every character, as James Lee Burke recently did so well in Flags On the Bayou, in which he wrote some scenes form the POV of enslaved black characters. Of course some would argue that as a white man, I have no right to judge whether he did that well or not. But I did the same thing in small parts of Southern Man—in flashback scenes during the Civil War—while simultaneously taking hard shots at some long-revered white writers like William Styron, for failing so miserably in this effort in The Confessions of Nat Turner, and then for being rewarded for his failure with our highest literary honors. These are complicated issues, and writers do have a responsibility, if we take on this kind of challenge, to “get it right” as best we can. You must also realize your own limits. I have nothing to teach Black people about Jim Crow that they don’t already know. On the other hand, a lot of white readers aren’t reading Ta-Nehisi Coates, Colson Whitehead, Toni Morrison, or even good Black crime writers like S.A. Cosby. It’s those readers I’m writing for, hoping that by seducing them into a powerful thriller involving race and cold cases based on real life, I can open their minds a little and get them to think about this country of ours in a different light, and from a different angle. Yes, even to make them see through different eyes.

MT: Of all your books, which would you want America to read today? What does it mean to you, and what do you want it to mean to the citizens of our country—or, in another sense, what do you hope they take away from this novel?

GI: Probably Black Cross, my second novel, which was set during World War Two and from a purely objective point of view is probably my best book. That said, I would like them to read the Natchez Burning trilogy, ending with Southern Man, which is sort of an unintended fourth-book climax to the trilogy. History itself—through the ascent of Trump and the outbreak of Trumpism, which revealed that millions of white Americans are ready to cast aside democracy in order to cling to power and privilege—practically demanded that I write this book. So I wrote right up to the edge of what’s allowed these days, and we’ll soon find out whether the result is greater success for having courage, as Burke did, or cancellation for crossing too many lines.

MT: Have you preferred writing series over standalones, or is the opposite true? When writing standalones, do you have any freedoms, capabilities, or needs you can meet in writing something that stands on its own over something that is going to be continued throughout a number of books?

GI: As I said earlier, I never intended to write a series about Penn Cage. Hell, I never intended to write any series. I much prefer to deal with the full arc of a character’s life in one novel, rather than having to revisit expository material with every book, that first timers won’t know. More important, it’s not realistic to show one person experiencing murder and trauma over and over in their lives, because that’s not how life is, not even for most cops. It’s the Murder She Wrote fallacy. One tiny town with a complicated murder every week? (Although in places like Jackson, MS or Baton Rouge, LA, we have murders almost every day). Better to have the freedom to compose your story from a person’s full life, or a big chunk of it. I could cite a lot of examples, but we don’t have space here. That said… I do love to read a good series, none better than the Aubrey/Maturin novels of Patrick O’Brian. Or at least that’s how I feel at this moment. I might give you a different answer three minutes from now. And of course, O’Brian himself once said he wished he’d known that Master and Commander was going to be book one of a series. If he had, he’d have begun earlier in Aubrey’s life and the Napoleonic Wars.

MT: Who do you look to as Penn Cage’s contemporaries, fictional private investigators, lawyers, cops, etc., who will also stand the test of time, with authors who perform excellently at peeling back the layers of a character or set of character solving crimes and uncovering truths? Which of these characters could you have seen Penn working alongside?

GI: Hmm… Rust Cohle and Marty Hart from True Detective, Season One? Their stomping ground is very close to Penn’s, and they dealt with the same kind of uniquely Southern corruption—both financial and moral—that Penn does. Just when you think you’ve gotten to the bottom of the mine, it gets a little darker and more twisted. As mayor or D.A,, Penn could have worked with those guys. And like them, he’s had to cross the line many times simply to survive, much less to defeat his enemies. Again I go back to Peter Straub. Penn shares some qualities with Michael Poole, the pediatrician (an unusual protagonist for a thriller) and Vietnam vet in Koko, and also with Tim Underhill, the author (and friend of Poole’s) in The Throat.

MT: Genre fiction can often be looked down upon (even if I often compare you to being the Pat Conroy of mysteries, just in my personal opinion). There’s this whole idea that books which follow some similar rigid structure, like a mystery or a thriller, cannot be unique or stand out amongst other great novels, despite the genre having writers like S.A. Cosby, Laura Lippman, Sara Gran, and so on. How have you bent and molded the genre to fit what you want your stories to be, rather than conforming to a series of recipes or how-to’s?

I’ve always been a rule-breaker. I know the rules, but I defiantly, even recklessly ignore them.GI: I’ve always been a rule-breaker. I know the rules, but I defiantly, even recklessly ignore them. Always have. I do what my stories require, period. I’ve followed this path across several genres, never much worrying about what box I’m “supposed” to be writing in. From my reading, I’m well aware of the tropes of various genres, and it may be that unconsciously I adhere just enough to “the rules” to make a living at this game… but it’s never been intentional (except during an especially fearful phase after my initial cancer diagnosis. I passed up a lot of chances in Hollywood at that time, because writing novels was already paying reliably and well). The only thing I can say for certain is that in all my books, I’ve always pursued the nature of what we call evil, no matter where it’s to be found, whether in a trailer park on the wrong side of the tracks or in the cherry-paneled study of an antebellum mansion built by enslaved artisans. I’ve pursued heroism the same way. Jack Higgins’s WW2 thriller The Eagle Has Landed showed me as a boy how a gifted writer can make a hero of a German soldier during World War Two. Hans Hellmut Kirst did the same thing in Night of the Generals. Probably the greatest surprise of my life was reading that Stephen King, when accepting his National Book Award, said that the judges who give out those prizes should look more closely at so-called genre writers, and he mentioned me by name among some others. I’m pretty sure that’s the closest I ever came to having a heart attack—at least while reading. To hell with genre-boxes, man. I could tell you about the wife of a famous literary writer who confided to me that deep down her husband just wished he could just sell more books—a lot more—and that he’d write more commercial novels if he knew how. That was another satisfying moment, I must say. Because literary writers who actually do that always say they just wanted “to experiment with” genre fiction, like they’re slumming on a dead weekend and have nothing better to do. But they always happily take the money, if they get it. And it’s the fame they want most of all.

MT: I like to think that crime fiction, mysteries, thrillers, and suspense novels stand out and are so popular because they provide a place for reason where, in real life, there may be little explanation behind the horrors we experience. Why do you think people still read these novels, making them one of the most popular staples in American literature, as well as consuming various forms of mysteries and thrillers on television?

GI: Everyone, from early childhood, is deeply curious about the motivation of evil acts, both in others and themselves. It’s a survival mechanism, I suppose. Fiction and drama that delve into these areas are some of the few ways that people who aren’t cops or physicians or psychiatrists or priests have to plumb the depths of the human psyche. For this reason, the popularity of those genres will never die.

MT: What’s your biggest regret out of everything in your career? What’s the one thing you’d have done or said differently? Is there a story you’ve left untold, or a novel you’d love to rewrite?

GI: I have several fully finished novels in my head. I can even give you their titles. The Select. Superluminal. Beasts of the Field. 44. The Bayou Dragon. From the titles you can probably guess that some of these fall well “outside the box.” Now, earlier I said that I recognize no box, or at least I don’t accept the tyranny of the box. Obviously, there’s a limit to this philosophy if you want publishers to keep paying you to write. But if a story is good enough, from the first line, it’s amazing how quickly that genre box disappears. And some of these stories have been haunting me a long time. Now that I’m fighting cancer, I have to be very careful in what I choose, because I don’t know which book will be my last. But that too, in a way, is a freeing thing. And I’ll take freedom wherever I can get it.

MT: Other than Penn Cage, what character have you loved and been intrigued by the most? Who else would you love to revisit in another novel, in another story?

GI: Cat Ferry, Harper Cole, Jordan Glass, Tom Cage (whom I’m revisiting in what I call “my Elvis book,” but as a much younger man).

MT: Why is it so important to revisit the history of the South again and again and again? I know I work in a high school where children will throw around comments about Hitler, but not be able to identify facts about the Holocaust (or, worse, understand the Holocaust actually existed). Do you think the tremendously dark and tormented history of the area we both call home is at risk of being forgotten too?

The first problem is the historical ignorance of Americans in general. Second, much of the history that Americans think they do know is Lost Cause crap—utterly inaccurate—yet they refuse to believe that, even when confronted with absolute facts. Where does this stubborn stupidity come from? It’s based in emotion, which is usually tied to family history. My God, the Holocaust is the most exhaustively documented genocide in history. There’s film and still photographs of some of the worst war crimes. Yet still large numbers of people continue to deny that it even happened. At least Germany as a nation acknowledged—under duress–the crimes of the Nazis, and took great pains to incorporate that history into their educational system. The American South has never accepted the actual causes, events, and broad effects of the Civil War, especially as they involve race and chattel slavery. We are now living through the absurd tragedy of that vast ignorance, and of the false history put into our textbooks, nonfiction books, novels, and films after the Civil War by groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy. And it isn’t only the South that’s never truly acknowledged the crime of slavery. Many white Americans who live in the North and the West never did either. This year’s presidential election will reveal a lot about just how deeply the poisonous virus of Lost Cause mythology runs in the 21st-century American bloodstream.

MT: Mr. Iles, thank you for agreeing to talk with me about your life and your work. It’s been a dream of mine for years, so I am so grateful to have had this experience. I’ve loved following your journey, as well as Penn’s, over the years. Thank you for this.

GI: Thanks for the incisive questions.