Twenty years ago, a monster named Joseph Edward Duncan, III, murdered three members of the Groene family and took siblings Shasta, 8, and Dylan, 9, from their Idaho home to a remote campsite in the woods of Montana. When Shasta finally escaped, her experience followed her through life, impacting every aspect of her experience, as her trauma compounded upon itself. But maybe, eventually, she could find a way out of the woods…

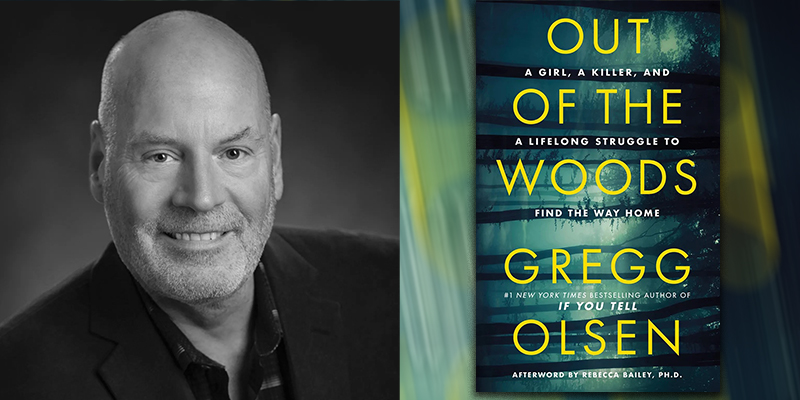

The following passage is adapted from Out of the Woods: A Girl, A Killer and Lifelong Struggle to Find the Way Home by Gregg Olson, Thomas & Mercer 2025.

The thing about trauma that many fail to grasp is that it frequently is a magnet for more of the same. That’s not victim shaming or blaming. It is simply a fact that left unchecked, trauma can manifest itself into other problems. Drug use. Lies. Trouble maintaining relationships. Shasta was the poster girl for that. She wasn’t oblivious to that or even a little unaware. She could see proof of the impact Jet had in nearly every aspect of her life. Yet there was nothing to stop it. Nothing worked. She made bad choice after bad choice. She lied when she didn’t have to. She took things when she didn’t need them. Shasta’s sense of self had been twisted, battered, and crushed by things that happened to her in the woods, but she was not a professional victim. That wasn’t how she saw herself at all, though she knew others felt that way.

The thing about trauma that many fail to grasp is that it frequently is a magnet for more of the same. That’s not victim shaming or blaming. It is simply a fact that left unchecked, trauma can manifest itself into other problems. Drug use. Lies. Trouble maintaining relationships. Shasta was the poster girl for that. She wasn’t oblivious to that or even a little unaware. She could see proof of the impact Jet had in nearly every aspect of her life. Yet there was nothing to stop it. Nothing worked. She made bad choice after bad choice. She lied when she didn’t have to. She took things when she didn’t need them. Shasta’s sense of self had been twisted, battered, and crushed by things that happened to her in the woods, but she was not a professional victim. That wasn’t how she saw herself at all, though she knew others felt that way.

Cops. Officers of the court. Her family. Friends. Strangers, even. Those factions and everyone in between watched the bravest little girl in the world become a young woman who appeared to court disaster. It wasn’t that she was asking for trouble. She just happened to find it wherever she went.

The Kootenai County Juvenile Prosecutor’s office charged Shasta with battery after she punched a boy who had taunted her at school in February 2013. Later that same spring, she ran away from home. When she returned, Steve phoned the police. During the call, the reporting officer overheard Shasta and her father go at it. No holds barred. She was arrested for that too. A short time later, she was charged with stealing another student’s laptop.

In the spring of 2013, Shasta was as high as could be, outside, walking. It was an hour before dawn. Trouble was coming for her.

“I could hear footsteps right behind me and I stopped that in my tracks. And he started walking towards me. And I started backing up and then he just threw me on the ground. I was covered in mud. My shirt was completely off. I just kept getting up and I just kept punching him as hard as I could. I just kept punching him in the face and punching him wherever. And I was just fighting as hard as I could. And then he finally just stopped, picked my phone up and walked away. He realized that I was going to keep fighting. I remember looking at him and I’m just like, this is not going to fucking happen to me again.”

Shasta knew that many in law enforcement in Coeur d’Alene had preconceived notions about her and was sure that no one would believe her story. When they questioned her, she was combative and evasive—and still very high. Officers seemed more focused on Shasta being out and about at that time of night than what had happened to her. Like it had been her fault. If, in fact, she was telling the truth. She was arrested for possession.

“That was the first time I went to jail,” she said later. “While I was there, I told one of the female officers that I wanted to pursue assault charges and start an investigation. The police gave me a photo lineup sheet and I picked the guy out right away. It was the same man that was running around raping college students at the North Idaho College. The police were like, oh, she’s faking it. Nothing even happened to her. And instead of anything, like, really happening or support getting pushed for me, I was grounded. And, you know, it just kind of made me feel like I was alone, you know? But then when I picked him out of the photo lineup sheet, I had all these people telling me how sorry they were and how they should have listened.”

Shasta was released only to find herself in more trouble in the fall of 2013. This time the incident involved her father and the big-screen TV she smashed. Violence had escalated between the two and neither felt safe. When the police arrived at the Groenes, Shasta was balled up on the sofa, crying and screaming because Steve told her that he was having her committed to Idaho State Hospital North in Orofino. He said he couldn’t trust her.

“You keep fucking running away!”

Shasta didn’t see it that way.

“You keep fucking kicking me out.”

The final straw came a month after Shasta turned seventeen. Shasta was no longer allowed at home without her father’s presence. At that point there was zero trust between father and daughter. He didn’t know what to do with her. She was using drugs and, he was nearly certain, was also selling them. She was hanging out with a rough crowd of teens who ran drugs for adult dealers. Shasta loved her brothers, and she knew they were far from role models. They’d been involved in drugs before the kidnapping and murders. Her mom, Mark, her father . . . all used drugs and lived at the very least on the fringes of that messy and scary world. Steve ran with a crowd of bikers. Drugs of all kinds came with the territory. After she was rescued, drugs were offered by a host of people who thought they might help her.

Forget.

Move on.

Or sleep at night.

All of that was utter bullshit. All it did was make her seek out more numbness and further avoidance.

_________________________