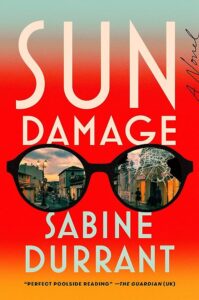

In TV, film, and books, both on our screens and on our bedside tables, con artists are rife. This year alone, four novels (“The Guest,” “Counterfeit,” “Scammer,” and my own “Sun Damage”) feature grifters as central characters. A slew of new TV shows, such as “The Dropout,” “Fyre,” “Inventing Anna,” and “The Tindler Swindler,” have emerged. Even the second season of “White Lotus” centres around a scammer. What is it about con artists that consistently captivates us? And how has our perception of grifters evolved in the realm of social media?

From “The Sting” via David Mamet’s “House of Games” to the long-running BBC drama “Hustle,” it’s the tradecraft that draws us in. The bluffs, double-bluffs, tricks, and twists, along with the ‘in’ language, “the mark”, “the set up”, “the tats” and “smacks”, turn crime into a theatrical spectacle. Observing a con artist is like watching a magician perform, clever and audacious, fun and intellectually satisfying. (See Sandra Bullock shamelessly navigating Bergdorf Goodman’s makeup department in “Ocean’s 8.”) The more intricate the scheme and the greater the display of manipulative skill, the more the viewer is on the edge of their seat, trying to anticipate the next move. In “Hustle,” a complex scam executed by a mismatched London gang often appears to go awry, only for the final scenes to reveal that the apparent misstep was part of the plan. This double twist adds to the relief as the viewer realises they, too, were conned.

Vera Tobin, a professor of cognitive science, suggests that real-life scammer Samantha Azzopardi, who deceitfully gained entry into Cambridge, worked like “a human page-turner.” She would lure people in with small confidences, test their vulnerability with bigger ones, and continue to surprise with twists and turns. If this is how it unfolds in reality, it is even more compelling in literature, where the con artist serves as an ideal unreliable narrator. In the early pages of Graham Winston’s “Marnie” (1961) or Emma Cline’s “The Guest” (2023), it’s the peculiarities that catch your attention (from the former: “everything I put on was new”). Moral ambiguity is evoked, as we encounter someone who may seem charming, sexy, or charismatic on the surface, but through their internal monologue, we know to be manipulative. It becomes a dual game of cat and mouse, where the con uses psychological tricks to exploit their victims’ weaknesses and vanities, while the reader is constantly trying to “read into things” to navigate their own path. Can the main character ever be trusted? Are they conning me too? In “The Guest,” written in the third person, we piece together Alex’s unravelling from the reactions of others. Winston takes a slower and more intricate approach, delving deep into the title character’s damaged perspective on men and sex. In a world where we negotiate the possibility of cyber-cons on a regular basis, it’s a cathartic process.

The fascination surrounding Anna Delvey, the fake heiress, who has become the subject of memoirs, documentaries, art, and pop shows, reveals much about our collective psyche. She appeared to be living the high life, frequenting top-tier restaurants and luxurious hotels, projecting an image of a perfect existence. However, when it was revealed to be smoke and mirrors (in the art show, one work, titled “Send Bitcoin,” portrays her in a red dress with her back turned to us in front of a computer), the discovery is both shocking and satisfying. On a daily basis, flicking through Instagram, say, we deal with a million tiny issues of trust and deception. Are they really that happy? Is there a filter? Is that picture faked? Life is uncertain these days. We seem to know so much about people – news and images at the touch of a button – and yet also less than we ever did. The rich heiress who it turns out is nothing of the sort, is like a snake in the grass, slipping into the places we might dream about – the posh hotels and best restaurants and most exclusive bars – and by doing so reveals them as somehow shallow. It turns out, if we are clever enough, they can be all ours for the taking.

***