Featured image courtesy of Warner Home Video

The three top-selling Christmas-themed children’s books released for the holiday season in 1957 were all stories of absence, loss, and theft: The Christmas that Almost Wasn’t by humorist Ogden Nash, The Year without a Santa Claus by soon-to-be-Pulitzer winner Phyllis McGinley, and How the Grinch Stole Christmas! by the beloved children’s author Dr. Seuss (the pen name of political cartoonist Ted Geisel). The three stories are all self-conscious about the precariousness of abundance, reflecting the decade’s newfound culture of plenty—the postwar snowball of American prosperity and the proliferation of the middle class—through the fear that it all might easily get taken away. Nash, McGinley, and Geisel (all born within years of one another in the very beginning of the twentieth century) had already witnessed two world wars, two periods of excessive prosperity, one nationally-traumatic economic nosedive, and the ongoing threat of intercontinental nuclear war—too familiar, by the midcentury, that “having” could, in a flash, become “having not.”

In The Christmas that Almost Wasn’t and The Year without a Santa Claus, Christmas disappears because of varying degrees of bureaucratic malfeasance. In the former, a usurper to a throne imprisons the ruler who officiates the Christmas celebration, thereby ending the holiday. In the latter, Santa Claus’s desire to slack off on his job and take a vacation means that Christmas won’t happen. (In both stories, children are able to fix these respective leadership problems and save the holiday.) In these tales, Christmas is represented as being contingent on the successful operation of a particular administration: it is a production. It must be effectively sanctioned, overseen, and staged by an authority on behalf of the people, and without these formal constructions, it cannot exist.

But How the Grinch Stole Christmas goes down a bit differently—it tells the story of an outsider with no formal power who deliberately connives to swipe Christmas from those who celebrate it, precisely because it bothers him that they do. The Grinch is a crotchety hermit who lives alone on a mountain that overlooks a village, Who-ville, that happily celebrates Christmas annually. He watches them celebrate, year after year, until he figures that if he steals everything from them, they won’t be able to celebrate. But when he makes off with all their decorations, presents, and foodstuffs, he finds that they still celebrate Christmas either way, and do so gratefully and joyfully. This shocks him. As the narrator says,

“… And he puzzled three hours, till his puzzler was sore.

Then the Grinch thought of something he hadn’t before!

‘Maybe Christmas,’ he thought, ‘doesn’t come from a store.

Maybe Christmas… perhaps… means a little bit more.”

The verdict in How the Grinch Stole Christmas! is that Christmas is indelible and non-material; it is ethereal and internal. It is about community, and love, and gratefulness, and so cannot be determined by material factors. The celebration will still happen, no matter what he does to try and stop it.

The Grinch, published by Random House with an initial (substantial) print run of 50,000 copies, vastly outsold Nash and McGinley’s books. Geisel had written it quickly, in just a few weeks. He was on a streak—earlier that same year, he had published the career-remaking success The Cat in the Hat. He did struggle, though, with the ending—which he sought to make as non-religious as possible. The story has long been understood as a criticism of the commercialism of Christmas (or even the capitalism of Christmas, or even capitalism in general). But its ending, in which the cranky burglar returns the items he had stolen and is welcomed by the Whos to their celebration, does also seem to suggest pretty strongly a theme of conversion—the discovery of faith in the meaning of the holiday amid all the tricky material trappings surrounding it.

Then again, unlike the television special A Charlie Brown Christmas, an equally-anti-commercial cartoon, in which the meaning of the holiday is explicitly presented as originating with the humble birth of the Christian Messiah, The Grinch steers away from anything so concretely faith-based. Save for the presence of Christmas trees and wreaths, the book is devoid of particularly Christian-appearing iconography; the Whos celebration resembles a festival, with an adjoining feast. (Its illustrations make the celebration look the way paganism might be imagined in a pop-culture context—hand-holding in circles and chanting.) In The Grinch, Christmas is a commemoration of giving, sharing, and love, plain and simple. “Ministers are reading a lot of religion into it,” Geisel wrote later on, “Ha!”

* * *

Purportedly, How the Grinch Stole Christmas! was inspired by the notion of unrecognizable humanity. “I was brushing my teeth on the morning of the 26th of last December,” Geisel is quoted in the December 1957 edition of Redbook, “when I noticed a very Grinch-ish countenance in the mirror. It was Seuss! So I wrote about my sour friend, the Grinch, to see if I could rediscover something about Christmas that obviously I’d lost.”

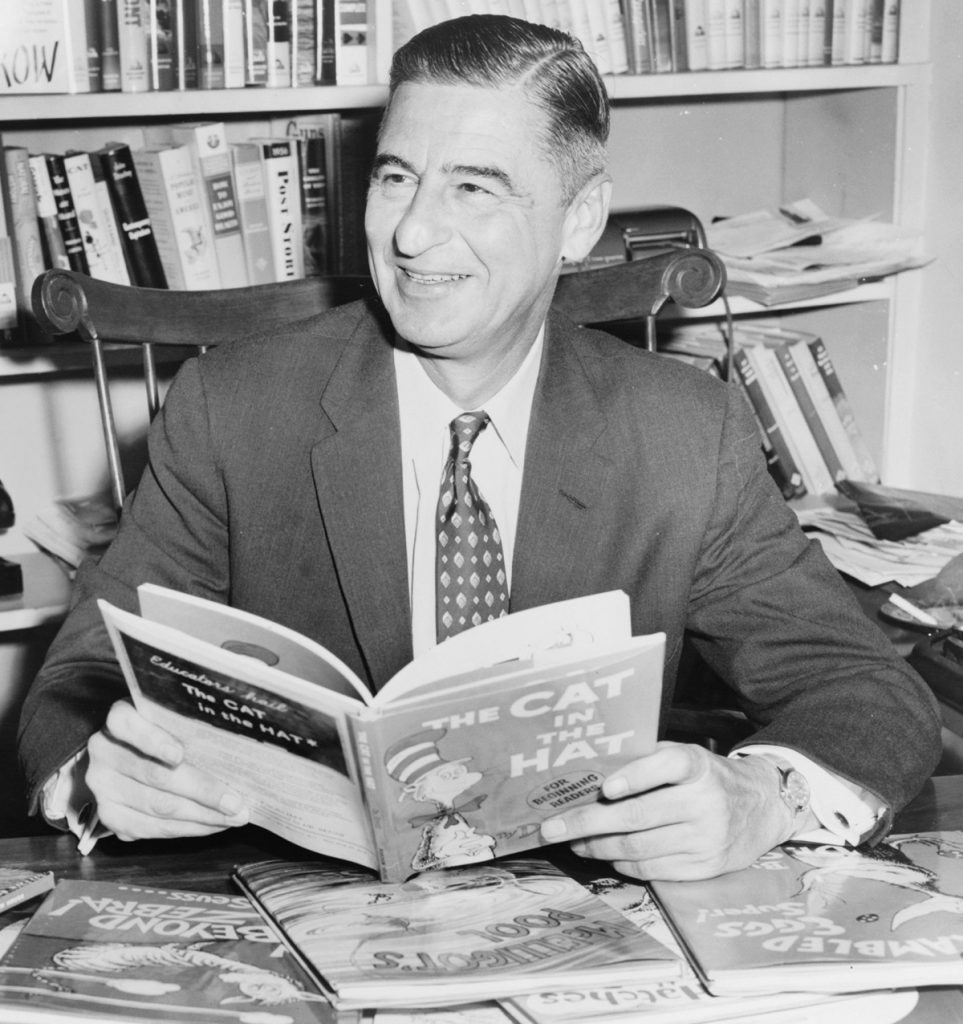

Theodor Seuss Geisel, circa 1957.

Theodor Seuss Geisel, circa 1957.

Geisel, though, had a long history of mixed feelings about Christmas. According to biographer Charles D. Cohen, as a student at Dartmouth College in the 1920s and a writer and cartoonist for the campus humor magazine the Jack-O-Lantern, Geisel lampooned the whole affair, specifically citing the greed and materialism he saw in the season in an essay called “Santy Claus be Hanged,” which was mostly about how Christmas mornings are ruined because no one receives the items they truly want. He bemoaned, “Sister wanted silk unmentionables and she gets burlap unpronouncibles. Brother wanted a case of scotch and he gets a case of goldfish.” A few years later, in 1930, he published a humorous essay suggesting that parents should combine Santa Claus, his reindeer, the Bogeyman, the Sand-Man, and the Stork into one home-invasive figure—simplifying the number of flying and/or magical creatures that kids would have to count on entering their homes. And then he drew many cartoons representing classic Christmas hallmarks in weird or comically unpleasant versions.

It’s unclear whether his publication of the book celebrated a new personal appreciation for the holiday, or if it was just convenient fodder for a story…

Geisel’s step-daughter, Lark Diamond-Cates, joked once that she thought that “the Grinch was Ted on his bad days.” And there are certainly a few more amusing parallels—the Grinch is cited as being fifty-three years old in the story (the age Geisel was when he wrote the book), and in his later years, Geisel was known to have purchased a vanity license plate for his car that spelled “GRINCH.” It’s unclear whether his publication of the book celebrated a new personal appreciation for the holiday, or if it was just convenient fodder for a story—as well as if his somewhat-public identification with the Grinch meant anything beyond a nod towards a mutual occasional cantankerousness.

Though the Grinch is a villainous protagonist, he is still a sympathetic figure, even before he changes his tune. He has been the source of many adaptations; since the release of the picture book in 1957, The Grinch has has been adapted to film three times: in an animated Television short from 1966, starring an elderly Boris Karloff, a live-action film from 2000 starring Jim Carrey, and a computer-animated film in 2018 starring Benedict Cumberbatch, as well as two stage musicals.

Holed up on his mountain, detesting the long hours of noise that Christmas will be sure to bring as the Whos sing and play with their cacophonous instruments and toys, he is not unsympathetic in his dislike for the hullaballoo and his desire for quiet. And the heist he pulls off is surely one of pop culture’s greatest—he robs literally everything from a village in a single night (including whole Christmas trees) with little preparation. It’s an impressive feat.

“…And the one speck of food that he left in the house

Was a crumb that was even too small for a mouse.

Then he did the same thing to the Other Whos’ houses

Leaving Crumbs too small for the other Whos’ mouses.”

It’s not often that Dr. Seuss asks us to sympathize with the agent of destruction, especially domestically-set. In The Cat in the Hat, we identify with the human children who are visited by the mischievous and impudent cat, are entertained by him, but ultimately vanquish him. But the Grinch’s audience follows him from stodginess to his heist to his eventual redemption.

The Grinch articulates a particular thesis that also speaks for and emblematizes the entire Seuss oeuvre: it is suspicious of the flashy and exciting things that distract us from our obligations, responsibilities, common sense, and wonder for natural things, rather than artificial ones. How the Grinch Stole Christmas! is an outlier in the Seuss canon for nearly everything about it—from its unusual perspective, to Geisel’s strong personal feelings about the subject matter, to the alacrity with which it was produced. But The Grinch articulates a particular thesis that also speaks for and emblematizes the entire Seuss oeuvre: it is suspicious of the flashy and exciting things that distract us from our obligations, responsibilities, common sense, and wonder for natural things, rather than artificial ones. Complicating the Grinch, and his story, is that while he does so many terrible deeds, he is motivated by something rather pure: the observation that a culture of increased commodification alienates us from what we owe to our community. But the Grinch also comes to embody that which he hates—and much else that is reprehensible—before he comes to terms with his own humanity. Ultimately, How the Grinch Stole Christmas! is not about what the Grinch discovers about the Whos and their lack of materialism, but about the hypocrisy of those who insist on their own superiority over those around them. The Grinch, who is rather an “ok boomer” kind of subject, is actually not totally wrong about his concerns about what is happening to the world. He’s just wrong to fervently, drastically, militantly conclude he’s so right.

* * *

How The Grinch Stole Christmas! is more in line with the tradition of Christmas stories helmed by Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, which seeks not to convert its main character from a disbeliever to a disciple, but from a greedy man into a caring one. When the main character of A Christmas Carol, the mean, wealthy skinflint Ebenezer Scrooge is transformed from his encounter with the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet-to-Be, his heart is described as finally being able to “laugh,” when it had previously been described as unable to feel any happiness or love. The Grinch’s heart, which had previously been “two sizes too small,” also undergoes a transformation:

“And what happened then?

Well… in Who-ville, they say

That the Grinch’s small heart

Grew three sizes, they say.”

The Grinch’s metamorphosis is notably, specifically represented as a “growth” of heart—not a “change of heart,” a phrase which is associated with particularly-Christian symbolism (the official term for it is “Metanoia”). The highly Protestant A Christmas Carol similarly skirts the representation of Catholic idols, preferring to epitomize and personify more general themes of caring, love, and community. In both texts, the holiday is represented with imagery of “plenty,” usually with toppling lists (think of the giant catalog of all the food at the feet of the giant Ghost of Christmas Present, along with the long, rhyming litany of all the components of the Whos’ feast).

Indeed, there are many parallels between the Grinch (whose name is adapted from the French word “grincheux”, meaning “grumpy”), and Scrooge (including the postmodern ubiquity of their names as monikers for the stodgy, nasty, and avaricious). The biggest is that they learn to participate in communities of love and giving, rather than passive-aggressively (or just aggressively) leer from the fringes.

But the Grinch responds to more archetypes than Scrooge, a character who has no earthly companions to love, and so whose aggregated crustiness is somewhat excused by years of solitude. The Grinch has a dog—a devoted, doe-eyed little dog named Max, whose undying love the Grinch scorns and exploits. The Grinch abuses him, tying a giant, heavy horn to his head and making him pull a massive sleigh down the mountain to Who-Ville. The Victorian literature professor Caroline Reitz has pointed out that the companionship of a loving but badly-used dog in The Grinch is not the stuff of A Christmas Carol—it’s the stuff of Oliver Twist. The novel’s main antagonist, Bill Sikes, who, like the Grinch, will manipulate children and use them in his thieving efforts, also has a sweet but ill-abused dog who follows him constantly, and who, in the novel’s climax, a chase scene, follows Sikes up to the top of a building where they both fall to their deaths. Like Bill Sikes, the depths of the Grinch’s villainy are also represented in terms of vertical distance and the corresponding symbolic emphasis on a fall; he also takes his dog for a climactic climb after stealing the Whos possessions; “Three thousand feet up! Up the side of Mt. Crumpit, He road with his load to the Tiptop to dump it.” It is on this mountain when he has a change of heart.

Like the Grinch, Sikes is not actually a miser; that job is unpleasantly left to the novel’s Jewish caricature, Fagin, Sikes’s partner and the other ringleader of the group of child-pickpockets. It goes without saying that the Grinch’s greater resemblance to Sikes than Fagin helpfully diverts the antisemitism almost endemically inherent to any character represented as desiring to destroy Christmas; but the Grinch also cannot help but participate in this tradition of caricature epitomized most famously in popular literature by the usurer Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, who is motivated by very little else than a hatred of Christians and Catholic-associated material idolatry and his desire to destroy a community of happy, wealthy Christians. That The Grinch avoids whether or not its protagonist is actually evangelized is useful; so much of this problematic literature centers on the question of conversion—that the villainous Jew must be purged by an erasure of some kind, death or renunciation of Judaism (Shylock, it is worth saying, is legally forced to change religions).

Making The Grinch resemble Sikes rather than Fagin, or even simply Scrooge, helps pinpoint a particular type of aggression endemic to the kind of behavior the Grinch exhibits towards his fellow creatures, rather than participate in a literary tradition which insists on the inferiority of non-believers or vilifies their non-belief. Broadly speaking, in much of Western literature until our recent moment (and often grappled with in our recent moment), Jewishness was represented as specifically being anti-Christian and advocating for the destruction of the Christian world—of subversive at worst and shameful at best.

But the Grinch, with his abject hatred of the specific-consumerism of Christmas, palpably embodies a kind of austerity that also feels somewhat Puritanical; he hates festiveness even as it is represented as an exception. He spends the year dreading Christmas, an indication that the Whos probably don’t throw this type of extravagant party at any other time. Rather like Scrooge, he doesn’t even understand taking one day off for festivity.

But, as indicated by the extreme cruelty towards his little dog (in such a way that often mirrors the behavior of one of the most sinister characters in western literature), the Grinch offers something much darker than existing to foil happy celebrations. Though the crook Fagin is a character construed through a particularly racist perspective, Sikes is clearly understood to be the real evil force in their novel. In our recent era, Sikes, a creepy loner, white sociopath who abuses animals and children, is the actual timeless evil whose presence in Oliver Twist was complicatedly distracted by the racism that articulated Fagin. But between them simply, Fagin’s moral failing is that he is greedy. Sikes’s moral failing is that he is full of hatred.

Far less moral than simply hoarding resources for oneself is taking resources that belong to others, and oppressing those thought of as weaker or lesser; it is important to remember that the Grinch is more than a miser or a grouch, he is a thief. He is a vigilante. He is an abuser. He is, in a way, a terrorist.

…It is important to remember that the Grinch is more than a miser or a grouch, he is a thief. He is a vigilante.

Part of this is that he is a supremacist. More than wanting to revel in the notion of the perceived supremacy of his own beliefs, he insists on harming others to fulfill this. He attempts to demolish the Whos’ ways of life, to give himself the knowledge that they are prevented from practicing their faith even while they are out of his sight. After the Grinch steals everything from their homes, he stands atop a mountain so that he can hear, and rejoice in, their despair—so he can experience and enjoy a community weakened and reeling from his cruel intervention.

Thus, in its skirting the urge to proselyte about anything particularly Christian, The Grinch finds itself slipping into eternally-urgent territory, telling a story about the necessities of religious acceptance and freedom in its chronicle of a loner-outsider who despises a group of people for celebrating their faith even inside their own community, and then who wages an elaborate attack on them in their private space to take a personal stand against it. Much of religious xenophobia that exists involves the insistence that people of other, “other,” religions are trying to specifically target Christians and take what they have, and The Grinch oddly, ironically represents that exact fear—that Christian communities might be targeted by obsessed, angry, and/or jealous outsiders, rather than what happens in real life in America, which frequently operates the other way around; that Muslim and Jewish places of worship are targeted by militant Christians.

This is not to say that The Grinch is purposefully an allegory for domestic terrorism or engages with any of these themes deliberately (even presciently or anachronistically), but that it crucially condemns an attitude that seeks to reject and hurt other people, according to ideological and religious principles. It condemns arguments about perceiving community, collaboration, and commonality as manifestations of inherent weakness and inadequacy and stupidity and inferiority. More than anything else, the Grinch is propelled by his hatred and his ignorance.

* * *

The Grinch made his first appearance several years before, in a short, folkloric poem Geisel wrote for the May 1955 edition of Redbook. Called “The Hoobub and the Grinch,” it is the story of a furry swindler called the Grinch, who tricks a naïve creature called the Hoobub into buying a useless product. It’s Aesop-esque and bears little resemblance to Seuss’s later book, except for its interest in the idea of the problem of the consumer: a witless worship of material goods.

A Hoobub is lying outdoors in the summer sun when a small yellow Grinch appears. “Along came a Grinch with a piece of green string. ‘How much,’ asked the Grinch, ‘would you pay for this thing?'”

A Hoobub is lying outdoors in the summer sun when a small yellow Grinch appears. “Along came a Grinch with a piece of green string. ‘How much,’ asked the Grinch, ‘would you pay for this thing?'”

And the Grinch cleverly proceeds to trick the Hoobub into thinking that the string is somehow more incredible than the sun. Part of this deception is simply yelling; the Grinch provides a loud advertisement, equal parts rhetoric and volume. The poem concludes: “And the Hoobub… he bought! (And I’m sorry to say, that Grinches sell Hoobubs such things every day.)”

The story, republished posthumously in a collection called Horton and the Kwuggerbug and Other Lost Stories,” is ambivalently canonical. If the Christmas-hating Grinch is part of a species of exploitative huckster-salesmen, this might explain, in a way, both his solitude and his own hatred of the commodification of the Holiday, and over-consumption of material goods, in general. The Grinch’s beef seems to be with the idea that objects can provide happiness; this is essential to his attack on the community. In taking away the material sources of their happiness, they will be unhappy, but they will also discover the artificiality of their happiness, in general. The Grinch’s attitude seems to reflect, somewhat, what Karl Marx referred to in Das Kapital as “commodity fetishism,” which is not the obsession with material goods, but a labor theory that focuses on the commodification of everything (and therefore the dehumanization of the worker), specifically arguing that subjective, abstract things are perceived as having objective, material value, in a capitalist society where all social relationships are re-construed economically. He seeks to punish them for putting price tags on happiness, but also in a strange and cruel way, educate them against this practice.

Thus, the domestic crime framework (if I may call it that) and extreme anti-commercialism of How the Grinch Stole Christmas! work hand-in-hand, in its presentation of a villain who is both very wrong and kind of right. The Grinch himself witnesses the veneration of something he believes is terrible capitalism and discovers is actually a peaceful religious exaltation, one which is rooted in love and is in fact un-materialistic. In his attempt to reject acquisitiveness and cupidity and extravagance (which are, granted, often associated with the holiday), he ends up committing a bad act and therefore taking a greater step away from anti-materialism and further embodying anti-humanity (which he had initially, with his condemnation of materialism, sought to express).

The Grinch is shocked to find that he has been wrong about the Whos—he stands atop the nearby mountain stammering to himself. “It came without ribbons! It came without tags! It came without packages, boxes or bags!”

Lo, the rather Puritanical Grinch becomes the only one obsessed with “things” on Christmas, as he attacks the Who community—suddenly reifying all of the book’s evils at once, all alone. And when he casts them off, upon hearing the Whos sing even if they don’t have any decorations or presents, he destroys them all together.

Many of Geisel’s books, from The Cat and the Hat, to The Lorax, are packed with the anxiety about losing true beautiful, joyful, and wonderful aspects of real life at the hands of diverting but artificial and dangerous substitutes—causing widespread neglect which inculcate significant long-term damage. The Grinch isn’t part of an epidemic, but he is able to identify one. The Grinch hates consumerism, materialism, and greed—his problem is that he thinks he sees it where it actually doesn’t live. And, of course, that he takes matters into his own hands afterwards. But all will be well; in the ultimate symbolism of the novel’s investment in community, he will take others’ hands in his, instead.