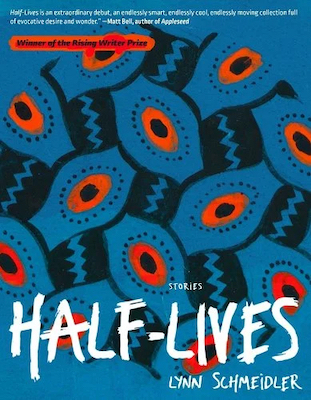

Read a full short story from the new collection by Lynn Schmeidler, Half-Lives.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere: in Lisa’s sixth-grade locker with her breath mints and roll-on deodorant; in Dr. Perlman’s walk—slow and tight-calved; in Mr. Robinson’s guitar, playing Cat Steven’s “Wild World” each afternoon before the bell; in Mrs. Taylor’s wavy, knee-length red hair, smelling of Wella Balsam and cigarettes. Sex was in the heat that gathered under the ceiling of the gym—when you climbed the rope to the very top, you came down smelling of it. Sex was baked into the raviolis Gina’s mom pinched shut around spoonfuls of meat while Gina snuck thick slices of last night’s chocolate cake for you to share upstairs as you admired her confirmation dress, all white eyelet and pearls. Sex was in John O’Connor’s towheaded curls, limp on his damp scalp as he leaned in to marvel at the hugeness of your thighs.

There were strong urges in contradictory directions: Gina’s older half brothers, so shaggy and sideburned that you asked to take your plate up to Gina’s room so you wouldn’t have to face them over dinner. Then you spied on them from the top of the stairs, blood pounding in your throat with every swallow. And Sam in your class, who you wanted to press against the wall and kiss, and whom you kicked instead, so hard he turned on you and screamed “what’s wrong with you?”

See Eros (life force) and Thanatos (death drive) in later psychoanalytic theory.

It was a land where everything was safe until it wasn’t: Ted Bundy, arm in a sling, waiting for you by every car. It was a land where you walked two blocks from school to the Luncheonette for a dollar twenty-five hot dog special, followed by a school-wide assembly introducing the Safe House program—“look for the orange Safe HouSe card in the front window if you need to ring the bell,” too late for little Maria-of-the-transparent-skin who’d returned to school with bruised cheeks and bloody veins in the whites of her eyes. And Mr. McMann was suddenly no longer the boys’ swim team coach because he was a “bachelor.” And Maggie told her mother something that made her mother fire the babysitter and then every week Maggie talked to a doctor named Leda while her mother waited in the car outside.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere, and there were body parts. Gina leaned into the window of a lost driver’s car to answer his question and his purple penis was propped against the steering wheel. Lisa’s father slept naked, and when you slept over, you saw his long white buttocks as he left the bathroom in the middle of the night (like quivering poached pears). One day, Teo, a distant older cousin from Israel, appeared and told your little brother (who told you) he liked to lick salt off girls’ breasts. The gardener’s son, rumored to be a rapist, worked shirtless in the backyard doing things to the flowers; his back rolled and glistened like a buttered croissant.

There was food. There was a seven-ounce smoked gouda devoured during General Hospital, followed by graham cracker sandwiches filled with Betty Crocker cream cheese frosting during Edge of Night. There were stomachaches, and there were fantasies of Baryshnikov and David Cassidy.

Insert here a feminist history of gorging and female sexual repression from the primordial to the postmodern.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere, and there was fever. It was the year of the chickenpox and then the extended family cruise on the Statendam: mothers in halter tops and Bermuda shorts sitting outside in the sun, silver reflectors under their chins, when you fell asleep on your stomach by the pool and your back crisped so that nothing—not Noxzema, not vinegar, not leaning forward for a week—nothing brought relief and you glowed heat and untouchability. And your sister sleepwalked onto the ship’s deck (she could have walked right off the boat into the moony ocean), and then went back to the bunk across from yours and snored with her mouth wide open beneath the ledge with the pennies she must have swallowed since they were gone the next morning. The rest of the week, your cousins calling, “Hey Drea, got change for a nickel?”

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere, and there were words whose meanings you pretended to know— ménage à trois and fellatio. And there were jokes whose punch lines you pretended to understand—Why does Dr. Pepper come in a bottle? Because his wife died. It was a land of intimations. There were Annie and Esme who cleaned the house on Tuesdays and Thursdays (lived together, had no boyfriends). There was the piano tuner who was a man one time and a woman the next (Peter to Peterpa). There was Harold and Maude.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere, and there were rumors: Mrs. Donoghue (divorced) and Mr. O’Hara (single) team-teaching, winking over your head. There was Lisa at the end-of-school dance, arms around Timmy’s neck. Why had you never seen him before tonight? And how had he gotten so tall without your noticing? There was the rock star whose stomach was pumped because of all the semen he’d swallowed, and Peter’s sister’s best friend who got pregnant from a toilet seat after her best friend got pregnant from her boyfriend’s pee. There were live gerbils and dill pickles in all the wrong places, and there was the spider that laid eggs in some girl’s cheek so when she scratched what she thought was a mosquito bite, hundreds of baby spiders crawled over her face.

Banisters were for straddling. The stuffed unicorn was for rubbing between your legs and then throwing in the trash when its horn smelled.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere, and there was fear. There was the drainage hole in the stone wall that opened into nothing but air over the quicksand inlet at the end of the dead-end block. And there was your neighbor Jimmy—square-chinned, squint-eyed, and broody—who you dreamed of kissing before he tripped on his stairs with his fishing rod in hand and the end of the rod went through his eye and into his brain. You stayed up all night praying he would live, that if God let him live, you’d be kinder to your siblings and less fresh to your parents, and he did live, but he was never the same. It wasn’t just the cane and the stiff leg he had to grab by the thigh and swing around the side when he walked. His face was crooked and he was moved to the special ed class, and when your parents invited his family over for dinner and your father asked him what piece of chicken he preferred (“I’m a leg man because the leg never gets old, are you a breast man, Jimmy? Come on, you’re a breast man, right?”) he just sat there with a half-grin on his face, and you wondered if your prayers for him to live were not specific enough.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere, and there was competition. There was Steven on his bike on your way home from school who you were supposed to ask to the square dance on Gina’s behalf, but who you managed to get to ask you first. There were tie-dyed shirts cut into strips at the bottom onto which you threaded wooden beads that clacked and clapped as you walked so Timmy would turn away from Lisa when you entered the room. There were dances you danced at the talent show so the boys could see your hips and poems you wrote for class so the boys could hear your voice. There were boys too skinny and boys too dull, boys not smart enough and boys not mean enough. Boys whose chairs you pulled out when they were about to sit down and boys you made sure you were cast opposite in plays.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere, and there were placebos—hooker costumes on Halloween, sleeping bags in the wayback of the station wagon. Catwoman and hot pants. Chest hair peeking out of collars and wrap skirts that flew open in the wind.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere, and there was a whole rich life of love. There were afternoons on the front lawn loving back walkovers and back handsprings, and there was running barefoot to meet the Good Humor truck at the end of the street (pretending the ice cream was for your little sister) and cutting your foot on a piece of glass and Lucy from up the street with her choker made of hemp, smelling like bubble gum and sixteen-year-old-girl sweat, lovingly carrying you back home. It was a land of tube tops and velour and somewhere in the future were your very own children waiting to be slung over your shoulder like the most adorable purse straps. There were swans’ nests in the reeds across the inlet at the end of the block. Potato bugs and daddy longlegs. Black-eyed Susans at the garden wall and, after two weeks in Vermont, a gigantic sunflower— dad-tall, plate wide—nodding its weird love.

Not everybody’s father was as handsome as yours. Lisa and Gina liked to come over and watch him play the guitar, admiring how his hands moved up and down the fretboard.

This section left intentionally blank.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere, and there were dreams—hiding that you could fly until you couldn’t take it anymore, then flapping your arms hard and taking off over roofs, naked and slick; dropped overboard from a boat and sinking to the bottom before realizing if you sucked hard, you could breathe underwater, slowly, thickly.

You were movie stars and murderers in the making. Some of you had big plans. Others went along. Two of you designed a restaurant that served only breakfast and dessert. Afterward, you made and sold painted dough pins in the shape of meaningful and repeatable objects— hearts, moons, roller skates. You were entrepreneurs and chauvinists and other French-sounding things.

Once upon a time there was no sex, but sex was everywhere—and there was death. There was the boy on his bike on his way to school caught under the 18-wheeler who you offered a minute of silence to during first period, though the principal wouldn’t say his name over the loudspeaker, and you couldn’t picture how it had happened and you couldn’t stop picturing how you almost could picture the truck on your bike, on your leg, on your chest. There was the Billig boy diving into the shallow end of the pool. There was the girl who walked onto the neighbor’s frozen pool and fell in and couldn’t get out and no one heard her or held her or saw her as she died, blue and alone. There was Jonathan Livingston Seagull all summer long, on the boat in swells—you were limitless, your body your own idea—with your parents saying, “when are you going to get your head out of your book and live a little?”

__________________________________