I arrived at an open gate, which invited me down a long driveway. It concluded in a dramatic semi-circle, crowned by a Tudor-style mansion. A lake gleamed behind it. There was a pergola for guests’ cars. I wondered if I should park there—was I a guest?—or at the edge of the circle, behind the housekeeper’s faded Corolla. This was where the Help parked, and I was at least Help-adjacent. I was the SAT tutor.

The usual dance commenced. A blonde woman greeted me and introduced me to a blond son. Pleasantries were exchanged. Books the size of small pets heaved out of trunks. Formal dining rooms consulted for ideal teaching conditions. Bathrooms admired covertly, kitchens spied upon. SAT tutoring is great work for a voyeur. The mother always wanted me to know her kid was smart, so smart, the smartest: tests just aren’t his thing. It’s fine, I wanted to say. As long as you keep inviting me to your mansion, as long as you keep paying me—we’ll get him into USC or NYU in no time.

The thing about being an SAT tutor is that functionally, you are little more than a con artist. The difference between my work, and the work of, say, the Tinder Swindler, is that mine has a patina of respectability. It is, by all accounts, publicly acceptable—even routine, in some coastal-elite circles—to pay an SAT tutor hundreds if not thousands of dollars to get your Ashleys and your Prestons and your Barons into Swarthmore. It might be more accurate to say that a private tutor performs the scam assist. After all, it’s Baron or Ashley who gets admitted through those ivied gates. The good-enough SAT score is a misdirection from the true guarantor of admission: the ability to pay the price of tuition.

I never thought I’d write a novel with an SAT tutor at the center of it. Tutoring was gig work I relied on for nearly a decade, but only that. It had nothing to do with me. It was just how I paid rent. For years my writing continued to circle the same old subjects—multi-generational familial traumas, nebulously gothic murder plots—but never my own labor. Never the primary urgency of my life: how will I make money today? How will I slowly chip at the mountain of my debts? How will I emerge unbruised from beneath the remains of my gullible faith in social mobility—the same faith that once made me apply myself, bootstraps and all, to the task of going to college?

The irony that all this work had amounted to was getting rich kids into college didn’t escape me. Tutoring was a job I’d stumbled into almost by accident. In high school I used to help my friends write their essays for class—a few of them solicited my services enough that they started to pay me for it. In college, desperate for money, I made a profile on a set-your-own-rate tutoring site. I’d never had a tutor myself, so I didn’t have a clue what I was doing or how to present myself, but eventually I had a couple of steady clients.

Gradually I climbed the professional ladder, but the view from the top offered little reward. My story was not special. Legions of hard-working former “gifted kids” were forfeiting their so-called potential to a labor market that never had a place for them to begin with. For the honors-students-turned-SAT-tutors who didn’t have the safety net of inherited wealth, our gifts were only useful insofar as we helped rich kids ace their math scores. I have ghostwritten the college essays of a handful of future sorority girls, plumbing the depths of their psyches in a Calabasas Barnes and Noble for some sob-story golden ticket that might earn them sympathy from an underpaid college admissions officer.

It wasn’t until I’d left the field and was juggling both a full-time tech job and a PhD in English (teaching duties included) that the idea for an SAT tutor crime novel came to me. Despite working full-time and pursuing yet another degree, I was barely surviving. I was working sixty hours a week, but I still needed another income stream to help make rent. I knew it would have to be SAT tutoring. The prospect filled me with existential dread. How was I approaching thirty, with multiple Master’s degrees and a full-time job, and still proving my credentials to some smug test-prep guru in Palo Alto? Between phone interviews and meetings, I found myself opening a Word document and jotting down “SAT tutor works for rich family. Shows up for work one Sunday and discovers dead parents and a kidnapped woman.”

It’s unsurprising, in hindsight. As my labor conditions suffered, intruding on every corner of my psyche, it seems inevitable that the gig work I’d survived on for so long would surface violently in my writing. A kind of psycho-geographic weather event, sweeping aside every half-baked family drama plot.

As I began writing—work that happened either late at night, or during whatever free time I had on weekends—it became clear how much horror and thriller fodder there was to be mined from gig work.

First there is the inevitable collision between haves and have-nots. I am a stranger to this family I tutor. They are strangers to me. And yet there I was every week, my shitty car parked alongside their Range Rovers and Porsches, my secondhand boots clicking on their gleaming floors.

To intrude on that space, to be privy to those insights and conclusions, always carried a suggestion of transgression. A stranger enters a mansion every week. A rich teenager does or does not follow their instructions. A family pays you. Your services suggest a grift, but one everyone is mutually participating in. You are a free agent—yes, you can choose your hours, yes, you go where you please—but you have no co-workers, no protections, no solidarity networks. I have worked as a waitress, in retail, as floor staff at a movie theater: places where you clock in and clock out, where you are surrounded by your fellow kind. As a tutor, or a maid, or a childcare provider, you are marooned, sometimes in the middle of nowhere, with your employer. Your cubicle is your crappy car. Your co-worker is a child, who is also your boss. Anything could happen to you in this stranger’s home. Or anything could happen to them.

There is a kind of horror in encountering wealth at that scale, over and over and over again. At first I was nosy: what writer isn’t? I wanted to know why. What skeletons hid in their closets? What white-collar crimes have they committed? How much suffering funded their fortunes? Their money was not glamorous—it was often ugly, garish, vaguely barbaric. The scales had long fallen from my eyes, but bearing witness to the monotony of money was still instructive. All along I was internalizing their habits, memorizing the layouts of their homes, eavesdropping on arguments between family members. I knew much more about them than they knew about me. Every week I came delivered to their doorstep, as anonymous as an Amazon package, and left. The power, of course, lied with them. But there was some small, latent danger in my invisibility, too.

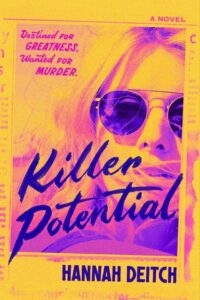

It was this seesaw of inequality I wanted to mine for Killer Potential. In my novel, an SAT tutor stumbles into a crime scene, discovers a prisoner, and is forced to become a fugitive, Thelma and Louise style. The press’s imagination goes wild, assuming our main character murdered this uber-wealthy Los Angles family as a kind of ninety-nine percenter revenge plot. It is the family, they assume, who are the innocent victims. It is the underpaid tutor who they label a criminal. The novel asks us to consider what kind of crimes we punish, and which we allow. At the heart of this story are fugitive outlaws, who must succumb to less-than-savory tactics in order to survive. I was curious how far our sympathy for them might stretch. For these characters, the open road is both a punishment and a perverse triumph, a balancing act in the scales of justice—and an escapist fantasy for my own burned-out mental state. At least she no longer has to work.

***