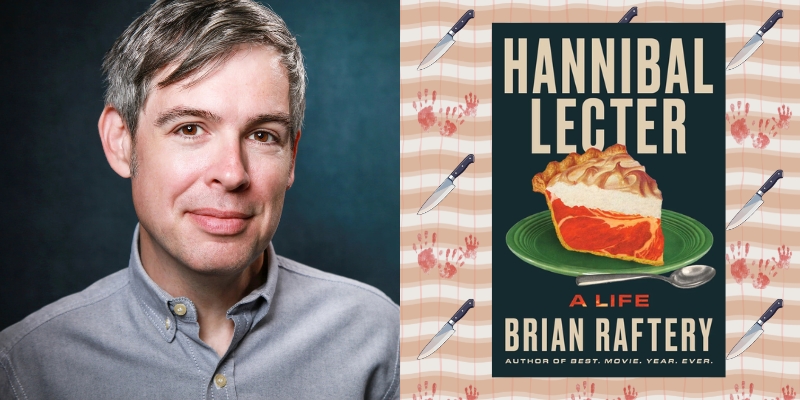

At the core of Brian Raftery’s latest book Hannibal Lecter: A Life (February 10, 2026) lies a mystifying question: how does one set out to write a biography about one of America’s most elusive writers?

Thomas Harris, the enigmatic creator of Hannibal Lecter, has spent decades avoiding the press, granting only a handful of interviews over the course of his career and leaving behind little in the way of a public record. But as Raftery unravels the secret history of the author, told mostly through secondary material, he also tells the tale of the notorious cannibal with a caustic wit, unbounded worldliness, and a smoldering if not lethal gaze.

Lecter, as the biography explains, was the product of one man’s endeavor to capture a mid-century American zeitgeist dominated by serial killers who roamed the streets largely unnoticed. At the same time that Harris was working as a newspaper reporter and immersing himself in FBI culture, patterns of serial violence began to surface across the country, with figures like Ted Bundy, Edmund Kemper, and Charles Manson coming to shape a new and unsettling category of American criminality.

In this, Thomas Harris seized on an opportunity to translate this phenomenon into fiction, a process that would propel his stories into the mainstream even as his own remained largely hidden.

I spoke with Raftery on the lingering effects of sensationalized crimes, the enduring legacy of one of America’s most revered pop-culture characters, and how he went about portraying a writer who never intended to be seen.

*

Hassan Tarek: Before you started working on this project, what initially drew you in? Was it Hannibal Lecter as a character, Thomas Harris as a figure, or something else entirely?

Brian Raftery: It’s funny. I think at a certain point, my interest in Tom Harris equaled my interest in Hannibal Lecter, especially as the more research I did into Tom Harris and realized how little research material there was. I really wanted to do a book that would let me look at a bunch of different cultural worlds at once. I’m very interested in the publishing industry, I’m very interested in Hollywood, I’m very interested in politics.

I was fascinated by the fact that Hannibal Lecter, despite being kind of a supporting character when he started, and despite the fact that there had only been a handful of books, was bigger than ever by the time we were talking about this book in the 2020s. How does a character who goes from maybe eleven to twelve pages in a book in 1981 go from relative obscurity to a beloved pop culture figure? What does it say about us that we’ve embraced him this way?

His crimes are so heinous that it was wild to me that he’d become almost like a Funko Pop. Where did this come from?

I was also very interested in how these books and films came together. I love The Silence of the Lambs. It’s a movie I’ve seen more than a dozen times. Researching it was a big draw. The book really widened when my editor suggested making it about a character who has never gone away from the culture.

HT: This book is a biography of Hannibal Lecter, but it’s also deeply about Thomas Harris. Early on, you trace Harris’s years as a working journalist—at the Waco Tribune-Herald, the AP, and through freelance work covering crime and violence. How important were those reporting years in shaping how his fiction works?

BR: They were crucial. He started out as a newspaper reporter and ended up a bestselling novelist, but he never stopped being a journalist. He did gnarly freelance crime investigations, encountered strange characters, and saw how police work functions up close.

What’s fascinating is how he took those skills into Black Sunday and Red Dragon. Black Sunday was a huge bestseller in ’75. He talked his way into the cockpit of a Goodyear blimp. His writing has always been fueled by curiosity.

For Red Dragon and The Silence of the Lambs, he talked to the FBI and got a granular look at crime sciences. He gets access and answers his own questions without answering to a newsroom.

HT: You follow Hannibal Lecter across different forms of media, from Harris’s novels to film and television. How did you think about engaging critically with these different formats while constructing your portrait of the character?

BR: I approached it not so much as a cultural critic. I like to do reporting. I was thinking about how much time and how many pages to dedicate to each property. I always knew the middle of the book would be about The Silence of the Lambs. But Manhunter has become beloved, especially among younger movie fans.

I wanted people who love Silence, Hannibal, or Red Dragon to feel represented, but also wanted people who had only seen Silence to follow the whole book.

The Silence of the Lambs was always going to dominate, but the making of the lesser-known films was fascinating.

HT: I know this may be an unpopular opinion, but while I love The Silence of the Lambs, I find Manhunter even more psychologically disturbing.

BR: I mean, to be honest, I went to a screening of Manhunter in Los Angeles, I think in the fall of 2023 and Michael Mann was there, and it was very hard to get tickets. I was online at 9:59, tickets went on sale at 10:00, and they were gone by 10:01. So anyone who was in that crowd had fought really hard to be there.

And I was really shocked by how many younger people were there. There were people there to whom Manhunter is their Hannibal Lecter. Have you ever seen it in a theater?

HT: I wish I had!

BR: It’s really unnerving. It is as unsettling as that movie is on home video in a theater. Boy, it is really, when that music is pumping up loud and you’re just kind of like, really looking at Francis Dolarhyde, just sort of seeing how unhinged he is. It’s a really disturbing but really great movie.

HT: In tracing Hannibal Lecter, you also had to uncover Thomas Harris himself, a writer who is famously reclusive. How does one approach writing a biography that is, in part, about one of America’s most elusive authors?

BR: Before we even signed the contract, we knew Tom Harris was not going to talk to me. I only found three in-depth interviews with the press in the last fifty years, one buried in the back of a hard-to-find magazine that a librarian at Columbia or NYU tracked down. If this book works, it’s because librarians helped me find this material.

He also didn’t talk to the press, and many of his contemporaries had passed away. His agent had passed away. Many former newspaper colleagues had passed away. I did speak to his editor Carol Barrett and to FBI people who knew him well.

One of the real finds was Jonathan Demme’s archives at the University of Michigan. I spent a week with them—faxes from Harris, cartoons, notes. I went through his Texas newspaper articles and AP stories.

No one knows exactly why Harris made certain creative choices, but I was able to fill in a lot of his background. His elusiveness mirrors Lecter. I admire that he doesn’t give interviews. In 2026, that’s a rarity.

He’s not prolific. He lives freely. I kind of like that.

HT: Harris lived a highly itinerant, preparatory life by traveling extensively and interviewing people far beyond what any single novel would seem to require. What did his research process reveal to you about him as a person?

There’s a real meticulousness to his work. He gathered an enormous amount of detail, but he was always very good at boiling it down in a way that was accessible. I think of someone like Tom Clancy, who clearly researched the hell out of submarines, but then overwhelms the reader with technical detail. Harris knew which details would click.

Black Sunday is a great example. It deals with terrorism and international conspiracies, but what stands out are the small, granular moments, like how police communicate with the press in the 1970s, or how someone might physically transport a bomb. He gives you just enough to convince you it’s real without numbing you with information.

That comes from journalistic training: how to tell a story succinctly, how to know what matters. It’s also driven by curiosity. Like most journalists I’ve known, everything he did was motivated by a genuine need to understand things. He wasn’t embedded with the FBI because it was a lark or because an editor told him to—he really wanted to know. And by all accounts, he was a gentle but extremely thorough interrogator.

HT: Harris learned a great deal from the criminals, investigators, and observers of violence he encountered. In researching Harris and Lecter, did you experience any comparable personal reckonings—moments where you had to pause and process what you were absorbing?

BR: One of the reasons I wanted to write this book is that I’ve always been interested in true crime, even though I’m a bit squeamish. I knew there was a connection between Hannibal Lecter and the rise of ’90s and 2000s true crime culture.

What I didn’t fully grasp until I started researching was the sheer number of unknown, unsolved murderers in this country. I’d be fact-checking cases Harris had read about and going through newspaper archives, and you realize how many murders from the ’60s through the ’90s were never solved and never became famous. They weren’t Bundy or Dahmer. Some of these people were never even caught.

There’s something heartbreaking about how much violence fills the daily news. We like to think this is new because of the internet, but it’s always been there. Many of these stories were relegated to page two because they were the third or fourth murder of the month. Researching that every day, you almost become numb to it, and that was unsettling for me.

HT: You note in the book that The Silence of the Lambs was still in theaters when Jeffrey Dahmer was arrested. How did that overlap between fiction and reality shape the way Harris’s work was received and understood at the time?

BR: If you go back to Red Dragon, it came out after a wave of high-profile serial killers in the late ’70s such as Ted Bundy, Son of Sam, and others. By the early ’90s, after The Silence of the Lambs film, that culture surged again. Whether Harris predicted it or helped cause it, you can argue both ways….

The Dahmer timeline really struck me. People magazine literally called him “a real-life Silence of the Lambs.” Those two things became immediately linked. At first, the idea of a cannibal like Lecter seemed far-fetched, and then suddenly it didn’t.

Throughout the ’90s, serial killers were everywhere, on magazine covers, on primetime news, in TV movies, in books. By the time Hannibal came out in 1999, real-world serial killers had become more famous than Lecter himself. I’ve often wondered how Harris felt about that, and whether he saw any connection between his work and that cultural shift.

HT: Harris was keen on speaking with criminals as part of his research. Was there a real-life case or figure that stood out to you as especially significant or revealing?

BR: As far as we know, Harris only encountered a handful of actual murderers directly. Some influences are clear, like a doctor he encountered in Mexico in the 1960s, a cannibal case near where he grew up. But I don’t think there’s a one-to-one real-life Lecter.

And I think that’s scarier. If Lecter were based on a single person, that might feel calming. But when you look at how many killers share similarities to him, famous or obscure, it’s chilling. He didn’t come from one person. He came from this country and from decades of violence embedded in its history.

Lecter may not be American by birth, but he’s a very American character.

HT: After finishing the book, what is one thing you now understand about Hannibal Lecter that you didn’t when you first began researching him?

BR: One thing that really struck me rereading the books and rewatching the films is that Lecter is oddly relatable. He’s trapped, intelligent, admired. That’s a classic literary situation.

At one point I found myself thinking: if you had to be a serial killer, he’s the idealized version. He’s charming, respected, brilliant. Other doctors seek his approval. And for all the menace, there’s a reason characters like Will Graham and Clarice Starling open up to him. He’s an effective therapist, before he eats you.

* * *