On afternoon in September 1979, Linton Weeks was working at Volume One bookstore in Clarksdale, Mississippi, not far from Harris’s home-town of Rich, when a familiar-looking customer came through the door. The man wore glasses and a beard, and his head was covered in curls. It didn’t take long for Weeks to figure out his guest’s identity. For a while now, rumors had been circulating around the Delta that Tom Harris had come home.

Weeks played it cool. “Black Sunday was pretty good,” he said by way of greeting. “The fact that you are a good writer shone through it all.”

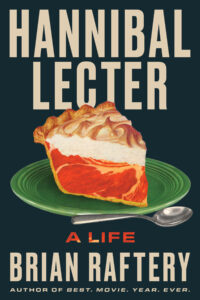

Harris nodded politely and expressed his gratitude. Then, in a quiet voice—which Weeks described as “Southern, worldly and charged with irony”—he asked for help in tracking down a particularly hard-to-find book: Alexandre Dumas’s 1873 cooking guide, Grand dictionnaire de cuisine.

It was an unusual request, one that Weeks initially took as “pure pretension.” He’d come to understand the significance of the Dumas book in the months and years ahead, during which Weeks and his wife, Jan, would become friendly with Harris. The couple lived in a cabin on nearby Moon Lake, and on some afternoons, the author would drop by with a pickle jar containing martinis, which the friends would drink as they sat and stared at the water. “The Mississippi Delta,” Harris proclaimed, “has the most beautiful sunsets of anywhere on earth.”

That wasn’t why he had returned home to Mississippi. Harris told Weeks he’d found it difficult to write in Sag Harbor—which very well could have been the case. But he had never strayed too far from the Delta. In 1978, Harris had enrolled in a Monday-night art class at Delta State University, where an impressed instructor had told him, “Your drawing is so good, you can illustrate your next book.” And by September 1979, he had relocated full-time to the family home in Rich to see his father, W.T., through an unspecified illness. The writer spent his days tending to the ailing W.T., and his nights in a neighbor’s shotgun shack in the middle of a large cotton field. That was where Harris worked on what would become Red Dragon.

While typing away in his shack, he could hear wild dogs panting as they roamed outside in the dark, their voices howling in unison during a full moon. On some nights, he would walk the fields himself, wandering far from the house. “When I looked back from a distance,” Harris wrote, “the house looked like a boat at sea, and all around me the vast Delta night.”

As he stood in the dim light of the fields, surrounded by little more than the sounds of snuffling dogs, his thoughts turned to Red Dragon’s troubled antagonist, Will Graham, a skilled former FBI profiler who left the Bureau due to a pair of traumatic events. Early in his career, Graham had shot Garrett Jacob Hobbs, a serial killer known as the “Minnesota Shrike”—an incident that had led Graham to seek help in a mental hospital. After returning to the FBI, he suffered a near-fatal stabbing, prompting a haunted Graham to quit the Bureau for good.

As Harris worked on his novel in that vast cotton field, alone after hours of tending to his dying parent, he found himself empathizing with his put-upon hero. “At the time, I myself was accruing painful memories every day,” he noted, “and in my evening’s work I felt for Graham.” That didn’t mean that Harris would take it easy on him. Red Dragon begins with Graham’s former FBI boss, Jack Crawford, pulling the ex-agent out of retirement. The Bureau needs Graham’s help in finding a murderer police have dubbed the “Tooth Fairy.” He’s a nocturnal killer who’s butchered two families in the suburbs of the South, timing his crimes to occur during a full moon, and leaving telltale bite marks on his victims.

Graham doesn’t want to be pulled into the hunt for another serial killer. But he can’t help himself. He has what Harris described as an “uncomfortable gift,” the rare ability to empathize with a killer’s motivations and methods—so much so, it’s as if Graham becomes the murderer, albeit temporarily. As Red Dragon noted, “There were no effective partitions in [Graham’s] mind. What he saw and learned touched everything else he knew. Some of the combinations were hard to live with. But he could not anticipate them, could not block and repress. His associations came at the speed of light.”

For Graham, tracking down the Tooth Fairy will be a devastating task, one that will require the help of the very person who, years earlier, had gutted him with a linoleum knife: Dr. Hannibal Lecter, aka “Hannibal the Cannibal.” The two men have a complicated past. But Graham believes Lecter’s the only one who can provide insight into the Tooth Fairy’s means and methods—and who can help the profiler understand how this new serial killer thinks.

Graham and Lecter’s first encounter in Red Dragon proved to be a struggle for Harris, for whom writing meant waiting. He described the novelist’s role as akin to being a companion or caretaker: His characters were the ones on a journey, and he was merely tagging along. “When you are writing a novel, you are not making anything up,” he explained. “It’s all there and you just have to find it.”

So it was with “some trepidation,” he noted, that he accompanied Graham on his trip to visit Lecter. As he worked in his cabin, writing Red Dragon, he followed his damaged hero as Graham descended into the bowels of the Chesapeake State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, where Lecter is kept in a maximum-security wing.* The first time readers meet Lecter, the doctor’s asleep on a cot in his cell, a copy of Dumas’s Grand dictionnaire de cuisine sitting open on his chest. He and Graham are separated by the steel bars of Lecter’s cell, as well as by a protective wall made up of floor-to-ceiling nylon netting.

Once Lecter awakes, it becomes clear that such restraints haven’t dimmed his powers. Blunt and bitchy—and eager to have a project—Lecter quickly makes Graham the topic of conversation. He quizzes the former agent about his emotional state, his dreams, even his aftershave (which Lecter, with his refined sense of smell, recognized as soon as the agent entered his lair). “Graham felt that Lecter was looking through to the back of his skull,” Harris wrote in Red Dragon. “His attention felt like a fly walking around in there.”

Their first meeting concludes with Lecter cruelly reminding Graham of the trait the two men have in common: Lecter may have murdered as many as nine victims (at least that the police know of), but Graham had fatally shot Garrett Jacob Hobbs. They may have been on opposite sides of the bars, but Lecter sees a murderous kinship in Graham.

“Do you know how you caught me, Will?”

“Good-bye, Dr. Lecter. You can leave messages for me at the number on the file.” Graham walked away.

“Do you know how you caught me?”

Graham was out of Lecter’s sight now, and he walked faster toward the far steel door.

“The reason you caught me is that we’re just alike” was the last thing Graham heard as the steel door closed behind him.

Harris wrote that first-ever appearance of Hannibal Lecter in a rush, his notes “spilling into the margin and over whatever surface was upper-most on my table,” he recalled. “I was worn out when it was over.” After Harris finished, there was a full moon over the cotton fields, and thirteen dogs were howling on the cabin’s front porch. By his estimate, he would go on to revise that initial moment between Graham and Lecter a hundred times. With each new visit to Lecter’s cell, he said, he whittled down the “superfluous static, the jail noises, the screaming of the damned that had made some of the words hard to hear.”

For Harris, the process of bringing Lecter to life had been exhausting—and unnerving. “I was not comfortable in the presence of Dr. Lecter, not sure at all that the doctor could not see me,” he wrote decades later. “Like Graham, I found, and find, the scrutiny of Dr. Lecter uncomfortable, intrusive, like the humming in your thoughts when they X-ray your head.”

If that humming felt familiar to Harris, it’s because Lecter reminded him of an old, ominous acquaintance: Alfredo Ballí Treviño, aka Dr. Salazar, the elegantly composed, hyperinsightful murderer who’d dismembered his lover in the late 1950s, and whom Harris had encountered while visiting Mexico for Argosy magazine. In a 2013 introduction to The Silence of the Lambs, Harris described writing the scene in which Graham approached Lecter’s lair. “Who do you suppose was waiting in the cell?” Harris asked. “It was not Dr. Salazar. But because of Dr. Salazar, I could recognize his colleague and fellow practitioner, Hannibal Lecter.” That line was immediately seized upon as evidence that Ballí was the “real-life Lecter”—a perception Harris later tried to discourage. “I won’t say he was the model for Hannibal Lecter,” the author noted in 2019. Certainly, the two killers had plenty in common. Both possess an icy verbosity and imposing manner—as well as what Harris described as “a peculiar understanding of the criminal mind.” The doctors even match up physically: In Red Dragon, Harris notes that Lecter is a “small, lithe man,” the exact term he’d use decades later to describe Dr. Salazar. And both prisoners stared back at their inquisitors through maroon-colored eyes (though only Lecter’s, Red Dragon notes, “reflect the light redly in tiny points”).

But to conclude that Dr. Lecter was “Dr. Salazar,” or vice versa, was the kind of reductive statement that would make Hannibal the Cannibal click his tongue in condescending disagreement. For starters, the two killers’ offenses and methodologies differed greatly. Ballí had confessed to just one murder, in which he had drugged, dismembered, and cut up a young lover before burying him in the ground. Lecter, by contrast, approaches his murders as though they were works of art. According to Red Dragon, one of his early victims was a hunter whom Lecter had stabbed, laced to a pegboard, and then adorned with arrows. As a finishing touch, he had rearranged the corpse so that the man resembled a vintage medical illustration known as “Wound Man.” Lecter wasn’t the kind of madman who’d stuff someone’s remains into a box and dump them into the ground—a déclassé demise, if ever there was one.

There’s another key difference between the doctors: Ballí’s murder was a crime of passion. Lecter, however, spent his early years killing for fun. “He did it because he liked it,” Graham tells a police detective. “Still does. Dr. Lecter is not crazy, in any common way we think of being crazy. He did some hideous things because he enjoyed them.” Those hideous things, according to Red Dragon, include an attack on a nurse who got too close to Lecter during an exam: “She managed to save one of her eyes,” Graham is told. “His pulse never got over eighty-five. Even when he tore out her tongue.”

By the time Harris wrote Red Dragon in his Delta cabin, he’d spent nearly half his life studying crime up close—from Waco to Mexico to New York City and various points in between. When it came to murder, he was an unaccredited scholar. And with Red Dragon, he was drawing on years of dark knowledge.

So while he no doubt saw glimpses of Ballí when he stumbled upon Lecter, there were other killers lingering in that cell at the Chesapeake State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. Lecter had the smarts (and apparent appetites) of the accused cannibal James H. Coyner. He had some of Charles Manson’s knack for intimidation and ingratiation. There were also similarities between Lecter and Edmund Kemper, both pragmatic conversationalists who’d tortured animals in their youth (an act that was “the first and worst sign” of violent tendencies, Graham noted in Red Dragon). And it was likely no coincidence that Lecter was conceived around the time newspapers were covering Richard Chase, the “Vampire Killer” who’d boasted of drinking some of his victims’ blood.

Ballí, Manson, Coyner, Kemper, Chase—by the end of the violent 1970s, they were all part of a larger swirl of sadism. And they weren’t alone; Lecter was an unnatural by-product of years’ worth of bloodshed—his small, lithe body containing a multitude of murderers.

You are not making anything up, Harris had said. It’s all there and you just have to find it. And in Lecter, Harris had found a plausible monster—one who would forever seem real not just to readers but to the author himself. “When in the winter of 1979 I entered the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane and the great metal door crashed closed behind me, little did I know what waited at the end of the corridor,” Harris wrote. “How seldom we recognize the sound when the bolt of our fate slides home.”

***

* In the initial printings of Red Dragon, Lecter’s home was referred to as the Chesapeake State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. It would be retitled the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in the novel The Silence of the Lambs.