Mickey Spillane’s I, The Jury, is often cited as a controversial mid-century crime novel. The book that introduced Mike Hammer sold only a few thousand copies when it was released in hardback in 1947 but became an international sensation in its subsequent paperback edition. The story of a private investigator out to avenge the murder of an army buddy ignited a storm of controversy throughout much of the world for its sex and violence, particularly the ending, in which Hammer slays an attractive female psychiatrist the same way she slayed his friend, shooting her in the stomach with a .45 pistol.

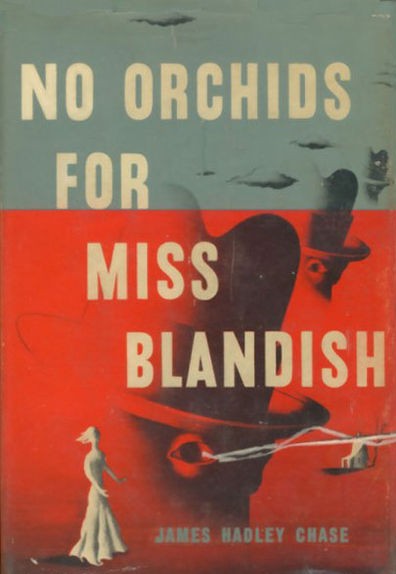

But appearing almost a decade earlier was an equally controversial crime novel, British author James Hadley Chase’s No Orchids for Miss Blandish. Little remembered today, No Orchid’s was condemned in Great Britain and throughout the Commonwealth for its explicit sex and violence, accused of glorifying crime, and banned in several countries. Despite this—indeed, probably because of it—the book sold half a million copies upon release in 1939, even with severe wartime paper shortages, and helped usher in a wave of hard-boiled gangster fiction, penned by British writers, much of it set in a heavily mythologized America. Their popularity ate into the market share of authors such as Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers, who had dominated English crime fiction for much of the interwar years.

A sheltered young heiress, the Miss Blandish of the title, is the victim of a robbery gone wrong aimed at snatching her precious diamond necklace. The robbers kill her fiancé and take her hostage, but word of the operation soon reaches the ears of the far more powerful Grissom Gang, headed by the ruthless Ma Grissom. They murder the kidnappers and take possession of their captive and her necklace. Ma promises to release Miss Blandish in return for a million-dollar ransom from her industrialist father but has no intention of making good on the offer. She pockets the ransom but is prevented from disposing of Miss Blandish by her knife wielding son, Slim, who has become attracted to their captive.

Despite fearing that Slim’s amorous designs will prevent the Grissom gang from disposing of the evidence of their crime and upset the tenuous control she excerpts over her psychopathic offspring, Ma agrees to let Miss Blandish live. She ensconces the woman in a suite in the nightclub the gang owns and dopes her up to make her compliant with her son’s sexual desires. Meanwhile, Blandish’s father employs a former crime reporter turned private eye to work with the police to find out what has happened to his daughter.

No Orchids is set in Kansas City and full of tough male gangsters wielding ‘rods’ and ‘Thompsons’, driving Buick cars, eating in greasy spoon diners, and trying to stay one step ahead of ‘the Feds’. While the book contains no more violence than the average 1930s American gangster film or pulp magazine tale, what is noticeably different is the sex, particularly Slim’s sadistic and prolonged rape of the doped-up Miss Blandish. Although he shows no details, Chase still manages to leave little the imagination. Ma and Slim Grissom are eventually gunned down by the police and Miss Blandish rescued. But as she comes out of her drugged state, Miss Blandish is unable to deal with the memories of her experience and jumps to her death from a hotel balcony.

***

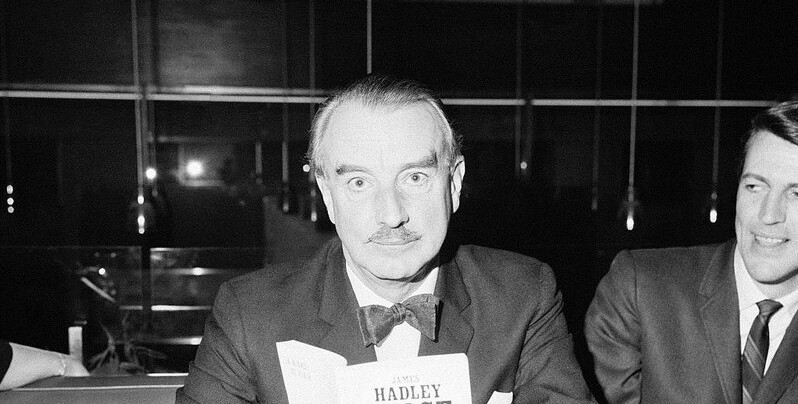

Chase’s wrote No Orchids, his debut, over six weekends during the English Summer of 1938. Born René Lodge Brabazon Raymond, Chase was notoriously interview shy and never discussed his work with the press or wrote introductions to his novels. What is known is that he was working for a book wholesaler handling distribution to retail outlets and what were known as ‘tuppeny lending libraries’ that serviced mainly working class readers, when he noticed hardboiled American crime novels, not traditional English fare, were most in demand. Some sources claim the plot of No Orchids was also inspired by a newspaper story about a kidnapped American heiress whose ordeal had driven her insane.

According to Steve Holland in his 1993 book, The Mushroom Jungle: A History of Postwar Paperback Publishing, gritty gangster tales set in large American cities such as New York, Chicago and Los Angeles first appeared to Great Britain in the 1920s via American pulp magazines such as Detective Fiction Weekly, Dime Detective, Spicy Detective and Black Mask. They were followed by the works of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Horace McCoy and W. R. Burnett. Chase was not the first British author to mimic American style crime fiction. Peter Cheyney’s This Man Is Dangerous, which introduced the fictitious FBI agent, later a private investigator, Lemmy Caution, appeared in 1936. Set in an imagined America, Cheyney’s novels were narrated in the first person by Caution in language that contained plenty of American slang. But Chase was the most successful, presiding over an explosion of locally penned American style hardboiled gangster and crime novels. Other prominent names included Darcy Glinto, the pseudonym for Harold Kelly, whose first novel, Lady Don’t Turn Over appeared in 1940; Hank Janson, a fictional character and pseudonym created by Stephen Daniel Frances, whose first book, When Dames Get Tough, was published in 1946; and Ben Sarto, a house name used for a series of luridly covered crime novels, the first of which, Miss Otis Comes to Piccadilly, was released in 1946.

The popularity of this genre of crime fiction was further helped by many factors. Blackout conditions left people with more time to read, resulting in a spike in book sales, a development further encouraged by the advent of cheap paperbacks, while war time restrictions meant that US pulp magazines and novels were not easily available. The resulting gap in the market was filled by a new group of British pulp publishers, eager to supply the public with cheap crime fiction. As was the case in the United States, the success of hardboiled fiction in Great Britain has also been attributed to the trauma of the Depression and the intrusion of violence into everyday life that occurred in World War II.

“Evidently there are great numbers of English people who are partly Americanised in language, and one ought to add, in moral outlook,” [Orwell] wrote.

The most prominent of No Orchid’s critics was George Orwell, who attacked what he saw as the story’s sadism and semi-pornographic nature in a 1944 essay. In sync with many other opponents, Orwell was especially critical of the book’s American styling, particularly the use of American slang. “Evidently there are great numbers of English people who are partly Americanised in language, and one ought to add, in moral outlook,” he wrote. “In America, both in life and fiction, the tendency to tolerate crime, even to admire the criminal so long as he is successful, is very much more marked.”

Chase would eventually face court proceedings for No Orchids and be fined for indecency. But at odds with its content and the furore around it, Holland asserts in his introduction to British Gangster and Exploitation Paperbacks of the Postwar Years (1997), that the novel originally had a sizable female readership. It first appeared in hardback and the book’s main sales outlet was the tuppenny libraries, mainly patronized by women. It was only when the paperback version it appeared that picked up a large readership of young working class and lower middle-class males.

***

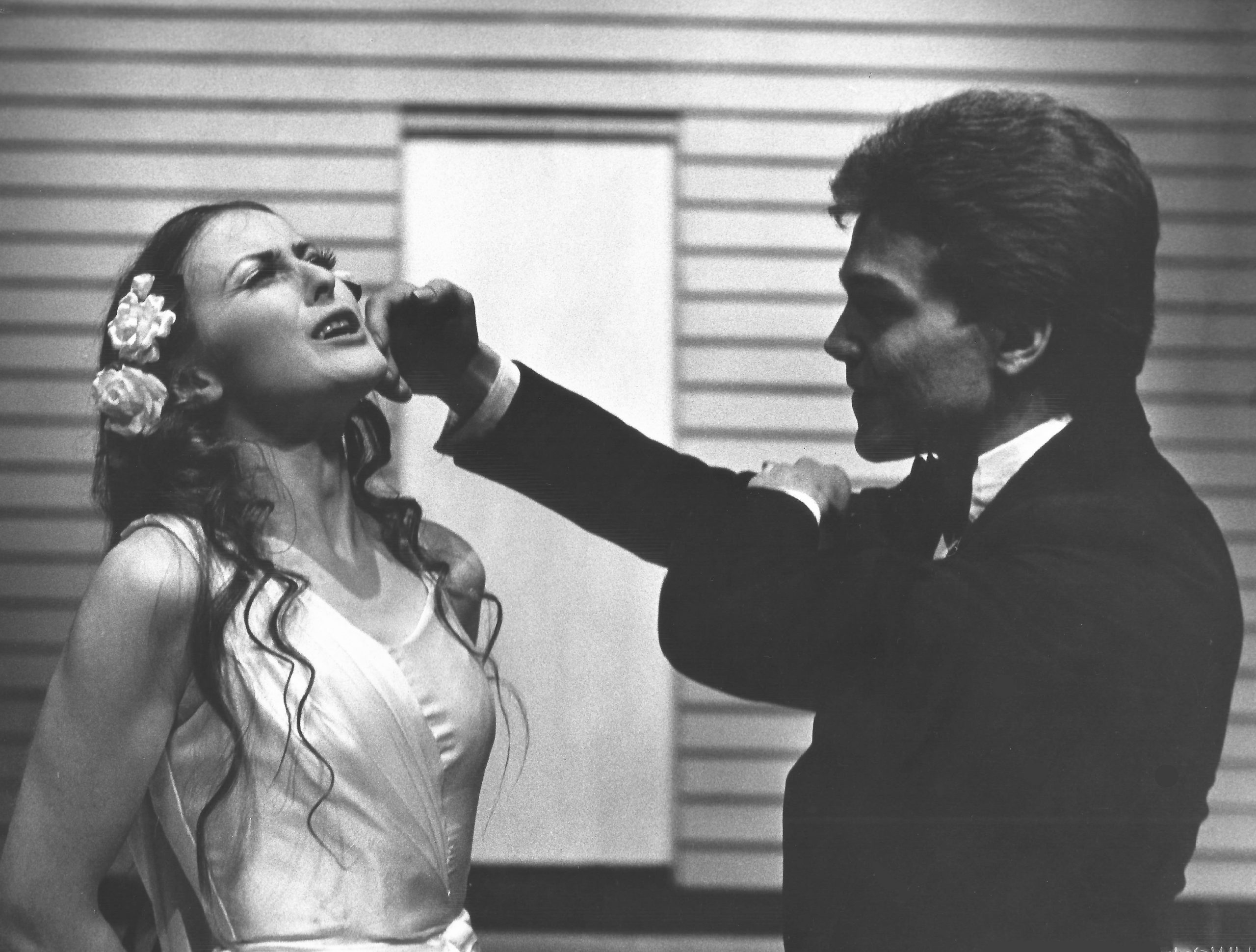

No Orchids was adapted for the stage in 1942, and a film version appeared in 1948. Shifting the action to New York but shot in England by a British production company and with a largely British cast, the film considerably toned-down the violence and sex of the source novel. Slim Grissim becomes Miss Blandish’s savior, rescuing her from the original kidnappers and protecting her from his own gang. The sexual relationship between the two is consensual and, in what is arguably a far more transgressive act than in the book, she decides to stay with Slim of her own free will rather than return home. After Slim dies in a hail of police bullets the rescued heiress, heartbroken over his death, throws herself over the balcony.

The changes did not stop the film from being condemned by the Bishop of London and both sides of British parliament. Monthly Film Bulletin labelled it the ‘most sickening exhibition of brutality, perversion, sex and sadism ever to be shown on a cinema screen.’ The Times film critic described it ‘an English film misguided enough to put on a knuckle duster and an American accent’. It was banned in several Commonwealth countries and in a number of American states, where it was released as Black Dice. Robert Aldrich helmed another remake in 1971, The Grissom Gang.

His 1942 novel Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief was banned in Britain and he was accused of plagiarism by Raymond Chandler in the late 1940s…

Chase would find himself the subject of several other court cases over the course of his career. His 1942 novel Miss Callaghan Comes to Grief was banned in Britain and he was accused of plagiarism by Raymond Chandler in the late 1940s, forcing Chase to issue a public apology. The Flesh of the Orchid, a 1948 sequel to No Orchids, was also widely criticized. Set in the United States, it focuses on the daughter of Miss Blandish and Slim Grissom, disowned by her stepfather, who is now dead. She escapes from the asylum where she has been placed for her homicidal tendencies and becomes a target for numerous predatory males who want her inheritance. No Orchids would also be the centre of international notoriety in April 1950 when Nicole Richie, the ‘vivacious, dark-eyed blond’ who played the role of Miss Blandish in the French stage production, went missing mid-performance, reappearing several days later claiming to have been kidnapped—although she subsequently admitted to the police that it was faked for publicity.

By the time No Orchids was republished by Panther Books in 1961, the publisher boasted the novel had generated sales of over 2 million and been widely republished overseas including in America. Chase would go on to write nearly 90 titles in a career that lasted into the early 1980s. And he continued to set his crime fiction in the United States well into the 1950s, despite never living there and making only two brief visits.