It’s 12° below zero, and Jerry Tracy wants Sam Volga dead. Volga is a killer. Tracy, New York’s most influential gossip columnist, is not. But he’s heard a rumor that Volga is in love—“carrying a torch,” in Broadway parlance—and he wants to use that weakness to put the hit man down.

“Here’s the news,” Tracy explains to a friend in the NYPD. “Sam Volga’s on fire. The smoke is rising from him.… Sam Volga, the big icicle, the hard guy! He’s still hard, but this time he’s hot. Do I sound interesting?”

“You sound kinda stupid,” says the cop, and he’s not wrong.

This is “Smoke,” a 1934 story written by Theodore A. Tinsley for Black Mask, the legendary pulp. It is one of 25 stories that star the sleuthing columnist—25 stories of overwrought slang, casual racism, and half-coherent plotting that I simply can’t put down. In a moment when lovers of problematic art are asked to be more critical of their taste than ever before, it is worth asking what it takes to enjoy sloppy pulp fiction in 2019—and why it’s worth the effort.

“Smoke” zigs and zags in classic pulp style, starting with an encounter in a nightclub, speeding past a vial of acid hurled at Tracy’s face, and climaxing with Tracy following Volga in a taxi, hoping he has succeeded in arranging for the hit man to die. The story is so twisty, and the dialogue so sodden with innuendo, that I had to read the first scene twice to be clear what the hell was going on. But it’s fascinating just the same, for reasons that start with Tracy. We’re told he’s, “barely over average height, quick, nervous, alert, dynamic,” and that “Broadway was stamped on his sleekly groomed person, in his wise, nasal speech.” This is Walter Winchell if Winchell had been imagined by Dashiell Hammett.

Tracy reeks of parody—think Jennifer Jason Leigh in The Hudsucker Proxy,—but Tinsley writes him with nuance. Yes, he can rattle off Runyonesque slang, spitting out sentences like, “Lemme try and dope this thing out… We don’t want Fred to gum up the works,” without a hint of embarrassment, but this is at least partly an act. Tracy uses his “brusque wise-crack comedy,” to put sources at ease, suggesting that even though he doesn’t think his jokes are very funny, they have a use. Beneath his wise guy patter, he has a heart of gold, but gold is cold and so is he. When he smiles, it is “a thin bloodless gash without merriment.” When he decides Volga has to die, he has no intention of letting the enforcer’s blood stain his gloves.

Because Tracy is a gossip, not a cop, Tinsley doesn’t need anything as gaudy as a murder to start his stories, lending them a variety rarely encountered in the pulps. Tracy’s profession gives him an unusual ability to influence events from afar, manipulating his enemies with the placement of a blind item in his daily column, and allowing the plot to speed along without resorting to typical detective story tricks.

Even when the plotting becomes dizzying, Tinsley’s prose carries it off. There is description in “Smoke” as sharp as anything in the hardboiled canon. Taking a bath, Tracy is “pink and parboiled and drowsy.” A corpse’s eyes are “wide with a kind of amazed, sleepy wonderment.” Volga’s terrified beloved is “in a tough spot. Straddled on a razor blade.” Leaving his first encounter with Volga, which leaves him frightened in a way most pulp heroes wouldn’t be, Tracy takes strength from air as icy as the prose:

“He bought back his hat and coat from a blond smoothie in black satin and pushed out into the biting cold air of the sidewalk. The dim street glittered with ice. The wind strummed like a harp.

‘Twelve below zero,’ the doorman mumbled. He spoke proudly, as though he had something to do with it. His face was purple.

Article continues after advertisementTracy breathed deep of the icy air and shook off the moldy smell of death. Assurance came back to him.”

The most striking passage in the entire story, perhaps in the entire Tracy canon, comes when Tracy is asked why he wants Volga dead, and he responds with uncharacteristic earnestness that it’s not a person’s murder he wants avenged—it’s the death of Broadway itself.

“’Broadway,’ the columnist repeated in a low voice. ‘Not the street, Danny. Not the car-tracks, nor the million lights. Not the cop whistles and taxi horns and the big shoes and little shoes going in droves north and south past the Astor flower shop—a million of ‘em shuffling in short-step formation every night. … The greatest street in the universe, Danny—but not the car-tracks or the chewing-gum ads.’

He took a deep breath. Talk raced viciously out of him.

‘Laugh, old-timer, and go to hell! Do you know what I’m thinking about, Danny? Old Pete Dailey and Lillian Russell and Georgie Cohan. Rector’s and Shanley’s and Murray’s. Top hats and opera capes and twenty-course dinners. Guys that could spend intelligently and women that were worth it. Real theatres along the Stem, not gold-plated movie coops for sixty-cent sports. Broadway! That’s what it was. That’s what it should be.’”

Article continues after advertisement

Jerry Tracy, the great cynic, loves no one but Broadway, and that honest passion is there to sustain our interest when the plot twists one time too many, when the dialogue turns cartoonish, or when the racism becomes too much to bear. And the racist elements of this story—as with much of the pulp canon—are considerable.

Slurs are used freely, and Tracy slips into one of several ethnic dialects whenever he’s hungry for a laugh. Most repellant, in 2019 or 1934 or any other year, is the character of his butler, McNulty, who speaks in predictably-awful Chinese dialect and whose face is described as, “plump and serenely yellow like a harvest moon.”

That’s pretty awful! So awful, in fact, that I wouldn’t blame you for picking up a copy of the book just to chuck across the room. But if you’re not the book-hurling type, these sickening moments provide an opportunity to ask ourselves what we will and will not tolerate in the art of a period infested by racism.

If you enjoy classic noir, then you have developed ways to cope. How do you do it? When you trip over a racist caricature or a casual slur, do you dismiss it as the inescapable residue of a bygone era? Do you skip to the next paragraph, telling yourself that while this story may carry a whiff of racism, it’s not as abhorrent as the worst offenders of the period? Do you sigh or curse or post about it on social media, and then press on, a little nauseous but fascinated nonetheless?

I can’t tell you how to push past the hideous depiction of a Chinese butler, because I don’t think you should push past it.I can’t tell you how to push past the hideous depiction of a Chinese butler, because I don’t think you should push past it. Better to marinate in those feelings, to interrogate them as best you can, and let them color your impression of the work as a whole. If that’s not possible for you, I don’t blame you for skipping these stories. If it is, you may find something interesting here.

For me, the Tracy yarns are a transfixing wreck of half-baked storytelling peppered with racism and enlivened by the occasional well-wrought character or piece of shining prose. This is, in Tinsley’s words, “high-pressure stuff [turned out] at top speed.” The messier it is, the harder it is for me to turn away.

Late in “Smoke,” as Tracy follows the cab that he hopes will carry Volga to his death, one paragraph reminded me why, as a writer of mysteries set in New York during Prohibition, I read the pulps:

“The cab turned through 57th, went south again on Sixth. At 53rd Street the frowning Elevated structure swallowed the taxi like a long, deserted tunnel. The avenue was icy and bare. It was very late. A trolley car clattered past, its ugly yellow-cane seats all empty. Overhead, a three-car train slammed northward and tiny particles of frozen snow sifted down from the steel crossbeams.”

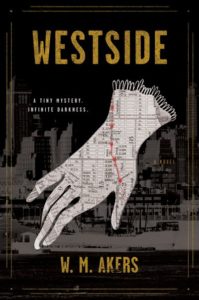

That reeks of New York, a New York that vanished long before I was born. In writing my novel Westside, which is set in a broken version of 1921 Manhattan, I used Tracy and the other pulps the same way I used old newspapers and pre-code movies and Joseph Mitchell essays and any other scraps from the period that I could find—as a portal to a city that, if it ever really existed, doesn’t anymore.

From Tracy I borrowed his cynicism, his false faces, and his love for his neighborhood, and leant them to my hero, amateur detective Gilda Carr. I took his city—bustling, glittering, and false—and turned it into something twisted by unknown evil. I left the hideous racism behind. I did this not just as a shortcut to writing historical fiction in a period I never lived, but as a way of purging this problematic old art of its hateful elements and refining it into something more worthy of my love.

At the end of “Smoke,” Tracy gets his wish. Sam Volga dies—killed not by the columnist, but by a cabbie seeking to avenge his sister, whom Volga destroyed. Tracy knows what the cabbie is planning, and he lets Volga get into the cab. When it’s over, Tracy inspects Volga’s corpse as the taxi radio plays, “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes.”

“Tracy looked at Sam Volga, at the sleek, well-fed jaws, at the faint smudges of black on the whites of the wide eyeballs.

“He said, ‘Yeah,’ in a flat, empty voice.

“He turned off the music.”

It’s not subtle, but it’s a hell of an ending, all the same.

***