In his introduction to the Black Lizard edition of Charles Willeford’s Miami Blues, Elmore Leonard writes that neither he or Willeford wanted to be stuck with the good guy’s point of view. “We both saw Harry Dean Stanton as our hero,” he said.

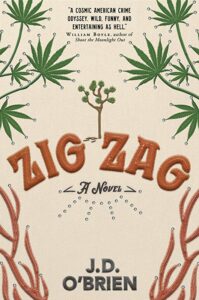

When I lived in Los Angeles, I haunted the bar at Dan Tana’s because I heard Harry Dean Stanton haunted the bar at Dan Tana’s. I spent a couple foggy closing times in his company, drinking tequila, smoking American Spirits, and singing Irish songs. Later, when I started writing about the burned-out Van Nuys bail bondsman who became the hero of my first novel Zig Zag, I always pictured Harry Dean.

Across a hundred or so movies, Harry was rarely the lead, but he was always a high point. Spaceship mechanic, Christmas angel, FBI agent, Paul the Apostle, Rip Van Winkle, Molly Ringwald’s dad. Plug him in anywhere and he works. On the surface, he could appear disinterested, ornery, hungover. Unwinding the cellophane on the day’s second pack, he did baby-I-don’t-care better than Robert Mitchum. But in all the drunks and lowlifes he portrayed, even in the cruel characters of The Rose or Big Love, his humanity always blazed through. It was right there on his face all the time. He looked like a fugitive saint.

With his hangdog mug and laconic fatalism, Harry was born to be in westerns—from early saddle and spurs roles on Rawhide and The Rifleman to wild riffs on the genre like Ride In The Whirlwind, Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid, Rancho Deluxe, and Cry For Me, Billy. But when you go down the rogue’s gallery of characters in the rap sheet of his filmography, you’ll find many who could float their own crime novels. Here are some of my favorites.

Low-Rent Detective

Billy Rolfe, Farewell, My Lovely; Ernie Fontenot, Playback; Johnnie Farragut, Wild At Heart; Rudy Junkins, Christine

Talking about noir, Farewell, My Lovely is as good a place to start as any. When Harry’s shifty department hack comes knocking, Mitchum’s Marlowe takes one look at him and says, “I have the feeling I should be slipping him a fin or something.” A small role, but Harry’s authentic performance is part of what makes this 1975 Dick Richards picture one of the best Raymond Chandler screen adaptations.

Only the most morally bankrupt Harry Dean completist need seek out Playback (it’s on YouTube), but even in this softcore Playboy production starring Tawny Kitaen and an extremely oily George Hamilton, you completely believe Harry as the cheap snoop digging up divorce dirt.

For Harry as P.I., you’re better off with Wild At Heart, David Lynch’s film of the great Barry Gifford novel. His Johnnie Farragut has a wide range—from down and out to completely out there—best represented in the famous scene of him barking like a dog in a motel room with a brandy snifter on the nightstand.

In John Carpenter’s version of Stephen King’s Christine, Harry has a Columbo quality as Detective Rudy Junkins. Maybe that’s why Carpenter pitched him the idea of doing a TV detective series. He mentioned it in interviews a lot, how it would have brought him more fame, money, and women, but he turned it down for a purely Harry Dean reason: “Too much work.”

Deadbeat Dognapper

Philo Skinner, The Black Marble

Based on a Joseph Wambaugh novel, this is an odd entry even for the Harry Dean canon. Philo “The Terrier King” Skinner kidnaps a high-end show dog to cover his gambling losses. Chain-smoking Camel straights, he calls in desperate ransom demands from gin mill payphones and is eventually found out by a bloodshot boozehound of a cop who chases him through a kennel in the bonkers climax. A self-described “mangy man” in white shoes, a white belt, and a rayon shirt open to the navel, Philo may be the sleaziest character in Harry’s repertoire, planted on a barstool right between Moe from One From The Heart and Billy from Rafferty And The Gold Dust Twins.

Bank Robber

Homer Van Meter, Dillinger; Jerry Schue, Straight Time

Dillinger doesn’t occupy the same space in my heart as their other team-ups in 92 In The Shade, Two-Lane Blacktop, and Cockfighter, but it’s always a deep pleasure to see Harry Dean and his Kentucky compatriot Warren Oates share the screen. Especially when they’re knocking over banks.

After Dillinger, it’s only a few years until Harry’s back in hold-up mode in Straight Time. Loafing poolside with a platter of cheeseburgers and a doting wife, Jerry Schue has traded in his ski mask and shotgun for a Hawaiian shirt and flip-flops—and he’s miserable. Soon as Dustin Hoffman’s Max Dembo hints at a robbery job, Jerry jumps at the bait with Harry’s immortal delivery of the line, “I don’t give a damn what it is, let’s do it…What is it?” That’s when you know everything’s about to go very bad.

Repo Man

Bud, Repo Man; C.W. Douglas, Flatbed Annie and Sweetiepie: Lady Truckers

Most of you have probably seen Repo Man. Some of you may be able to recite the Repo Code. Unfortunately, it’s almost impossible to find Harry’s first run at the repo racket in Flatbed Annie and Sweetiepie, a 1979 TV movie starring Annie Potts and Kim Darby. In the grand tradition of 70s trucker pictures, this is a shaggy, freewheeling affair. It concerns an 18-wheeler hauling cocaine with some interested parties in hot pursuit. Harry’s repo man looks like an emaciated Boss Hogg with his western suit and longhorn hood ornament—but he’s damn determined to get that rig. Also featuring Fred Willard, which is never a bad thing.

Shady Faith Healer Who Moves Stolen Cars

Brother Bud, UFOria (1986)

This movie starts strong with Fred Ward drinking from an open container in an open convertible. When he reunites with Harry Dean’s conman preacher, things really take a turn for the weird. A lot of the charm of this underrated gem is in Harry’s boozy chemistry with Ward, which recalls the dynamic he had with Warren Oates. Brother Bud’s philosophy is, “Everybody ought to believe in something. I believe I’ll have another drink.” Sounds a lot like the guy holding court at Dan Tana’s twenty-five years later, who was fond of saying, “We’re all gonna live forever. But I’m gonna outlive all you motherfuckers.”

Nowheresville Loner

Travis Henderson, Paris, Texas; Old Man, Fool For Love; Carl Rodd, Twin Peaks: Firewalk With Me/The Return; Lyle Straight, The Straight Story; Floyd Cage, The Pledge; Lucky, Lucky

Harry Dean created his own distinct version of the American loner archetype. A Zen cowboy. A man out of time. Starting with his defining role in Paris, Texas, written for him by Sam Shepard, you could argue many characters that followed are versions of Travis. Still on the drift, discovering again and again that all roads lead to nowhere.

In Robert Altman’s adaptation of Shepard’s Fool For Love, Harry’s character, known only as the Old Man, is ensconced in a junkyard trailer behind the neon mirage of the El Royale Motel, fantasizing about Barbara Mandrell. For Firewalk With Me, the loner decamps for the Fat Trout Trailer Park and a cup of Good Morning America in a plaid bathrobe. Then David Lynch drops him on the porch of a dilapidated shack for the haymaker final scene of The Straight Story. Come 2001, he shows up in The Pledge, operating a remote gas station outside Reno. When Jack Nicholson presents a turnkey offer, Harry wastes no time packing his fishing rod and hitting the road, eventually making his way back to the Fat Trout Trailer Park for an encore performance of “Red River Valley” in Twin Peaks: The Return. The loner finally comes to the end of the trail, as Harry does, in the desert town in Lucky, his small, perfect swan song.

***