I have worked in the film industry for nearly four decades in various capacities—from pyrotechnics to location scouting to screenwriting. Several years ago, one of my friends from Hollywood had purchased three adjoining apartments in one of the oldest parts of Paris that he wanted to renovate into a single living space. Because he lived abroad and traveled constantly, he asked me to oversee the construction. I knew absolutely nothing about building permits and construction but, for some reason, I agreed. One day, the workers tore down a wall and uncovered a small room containing just a table, a chair, some shelves, a whole lot of dust, and an old bottle filled with black liquid.

I was amazed by the secret room and became especially fascinated with the hidden door. To enter the room, you pushed back on the wooden wall and it slid open on a complex mechanism that was an incredible technical achievement—finely crafted, with the precision of a goldsmith or a watchmaker. I requested permission to temporarily halt the renovation, to try to figure out what the room was, and how it came to be. Going through the ownership documents, we found records dating back to medieval times and figured out that the room must have been constructed in the mid-1700s. A glass expert estimated that the bottle was from around 1720. The liquid was likely a port wine, but unfortunately it didn’t age well!

I started to wonder about who could have built such a room. Only a specialist could have crafted a secret passage like this one. And that’s how the idea for Vincent, the main character of The Paris Labyrinth, began to emerge.

That first secret led me into a labyrinth of research which became the book. Along the way, I discovered several other—entirely true—Parisian secrets. They might inspire you one day to come to Paris, to seek out and visit certain monuments, and to look beyond the surface. Discover how these and many more incredible secrets are woven into the plot of The Paris Labyrinth.

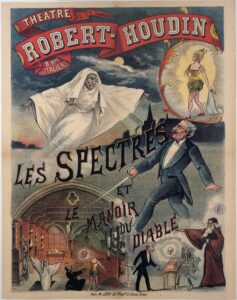

The Magic of Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin

An exceptional magician responsible for developing most of the great principles of his art and an inspiration to his successors, Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin is an extraordinary figure: an inventor, researcher, creator, and founder of a theater dedicated entirely to magic. It’s impossible to summarize the magnitude of his contribution and his personality in a few lines, but I encourage you to learn more about this man, who was unfairly forgotten in the shadow of Harry Houdini—the Austro-Hungarian Ehrich Weisz—who appropriated his name and many of his methods, largely relying on the media to build a sensational career in the United States.

Our remarkable role model Jean-Eugène Robert was born in 1805. He developed a fascination for mechanics as a child observing his father at work in a horology workshop. He became a watchmaker at the age of twenty-three. An encounter with a magician specialized in sleight of hand would change his life.

In 1830, he married Cécile Houdin, the daughter of a Parisian watchmaker, and added her name to his own. In the following decade, Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin focused his efforts primarily on watchmaking and registered several patents for inventions, including a lighter-alarm, which ignited at a scheduled time. He reinvested the money he made building automatons and entertainment gadgets, including a mysterious pendulum with no visible mechanism, into his research. Despite his financial difficulties, he was eventually recognized for his talent. A patron lent him the funds to create his writing-and-drawing automaton that met with great success at the World’s Fair in 1844. Following Cécile’s death, he devoted himself entirely to illusionism.

The first of his “Soirées Fantastiques” (“Magical Evenings”) was held on June 25, 1845. His illusions Foulard aux Surprises (Surprising Handkerchief), Pâtissier du Palais-Royal (Palais-Royal Pastry Cook), and L’Oranger Merveilleux (The Marvelous Orange Tree) caused a sensation. His fame grew when he presented La Seconde Vue (Second Sight), a divination exercise, and when he put his young son Émile in ethereal suspension. In November 1846, his shows were so successful that spectators had to reserve seats months in advance. King Louis Philippe I invited him to the palace for a special performance, and he also performed in London for Queen Victoria.

His own theater proved to be an exceptional laboratory for his illusions, where he developed trap doors on the stage floor and rope systems for sleight-of-hand tricks. Later, Georges Méliès would hold film projections there and drew inspiration from Robert-Houdin’s special effects for many of his films.

In 1855, Napoleon III called on him for help in fighting against the Arabic marabouts who were encouraging the people in Algeria to rebel. In June 1856, Robert-Houdin pretended to be an all-powerful sorcerer with supernatural powers by performing tricks like Le Fusillé Vivant (Surviving the Killing Shot) and Le Coffre Lourd-Léger (The Light and Heavy Chest). The marabouts’ influence diminished, though it did not disappear entirely.

Robert-Houdin installed many inventions on his estate: all of the electric clocks on the property were connected to an electric regulator and perfectly synchronized. The estate’s entrance gate was equipped with a bell and an electric strike so that it could be opened remotely. He also kept many of his automatons there.

Robert-Houdin also registered patents in a number of other fields, and some of his inventions, like the fencer’s electric plastron and the odometer, are still used to this day. He died on June 13, 1871, leaving behind no less than a hundred tricks that still fascinate and inspire generations of illusionists.

Le Chat Noir Cabaret

In November 1881, Rodolphe Salis—a wine merchant, aesthete, and poetry enthusiast—opened a cabaret on Boulevard de Rochechouart that he called Le Chat Noir, because he found and kept a black cat that was in the building. The establishment was eccentric and libertarian, and soon attracted artists and fringe elements who contributed to the scandal-soaked and festive spirit of the Butte Montmartre. Le Chat Noir became fashionable, attracting the capital’s talented writers, actors, musicians, satirical singers, painters, and illustrators, including Alphonse Allais, Charles Cros, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Aristide Bruant.

The cabaret became one of the first truly seedy establishments in the capital to overcome the social divide; it was also frequented by thugs and other petty criminals on the hunt for victims, which earned it frequent visits from the police.

Salis decided to leave the establishment to Bruant and set up shop in a larger building on nearby Rue Victor Massé, where he developed his extraordinary sets and his true vision for a cabaret: singers on the second floor and shadow theater—in color!—on the third. Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen created the famous Tournée du Chat Noir poster in 1895, after the establishment’s golden age had already come and gone, nevertheless giving it prominence in the imagery associated with bohemian Paris.

During the same period, Paris was in the grip of a feverish excitement over spiritism and paranormal activity. For several decades, “miracles” had no longer been the preserve of the clergy, and countless spiritualists, soothsayers, and magicians possessed extraordinary powers in which they traded at public or private seances for a wealthy clientele. There is evidence that several of these dubious characters gathered at Le Chat Noir starting in 1885. Many would be thwarted and their mystique stripped away, but some—more skillful or truly gifted with powers—fascinated the public and earned themselves a genuine reputation. One of them, Le Grand Orion, performed alone; but it was suspected that he had a twin, enabling him to appear in two places at once. He was accused of fraud and eventually fled to Switzerland in 1890. At the time, he was thought to possess genuine psychic powers that he supposedly used to establish his authority over a cult.

The Alchemist Nicolas Flamel

Between 1397 and 1407, Nicolas Flamel—who is remembered as an alchemist—had a mansion built for himself in Paris that he never lived in. Currently located at 51 Rue de Montmorency, the house has retained much of its original appearance despite several partial reconstruction efforts, notably in 1900 when its gable and high windows were modified. It is the oldest house in the capital that can be dated with any certainty, and the facade has been classified as a historical monument since 1911. Today it is a restaurant.

Flamel offered lodgings to workers and the needy, on one condition—that they say a prayer every day. No one could explain Flamel’s extraordinary fortune, which he often used to philanthropic ends, earning himself the ardent admiration of alchemy enthusiasts to this day. The original wording, inscribed across the pediment, is still visible: Nous homes et femes laboureurs demourans ou porche de ceste maison qui fu fte en lan de grace Mil quatre cens et sept, somes tenus chascun en droit soy dire tous les jours une patenostre et I ave maria en priant dieu que sa grace face pardon aus povres pescheurs trespassez, amen.

(We, men and women laborers, living in the entryway of this house that was built in the year of our Lord 1407 are all required to recite an Our Father and a Hail Mary daily, praying to God that his grace brings forgiveness to the poor deceased sinners, amen.)

***