Between the two of them, Hilary Davidson and Susan Elia MacNeal have a formidable collection of bestsellers and award-winning books. While their novels are set decades apart—Davidson’s in contemporary times and MacNeal’s in World War II—both write about women facing daunting challenges. As long-time fans of each others’ work, they realized they explore issues around trauma and the scars it leaves behind. The characters they portray navigate territory that for both authors is also personal. That led to a conversation about how women process violence, PTSD, and what it’s like to write about a subject that can be too close to your heart.

Hilary Davidson’s latest novel, Don’t Look Down (published on February 11th by Thomas & Mercer), is the sequel to last year’s bestselling One Small Sacrifice. NYPD Detective Sheryn Sterling returns with her partner Rafael Mendoza—still recovering from extensive injuries—to investigate a case of blackmail and murder that appears open and shut. When a man is found shot dead in Hell’s Kitchen, the evidence points to a successful young entrepreneur with a troubled past as his killer. But Sheryn can’t let go of small details that don’t add up, and as she follows them, the case becomes far more sinister… and deadly.

Hilary Davidson’s latest novel, Don’t Look Down (published on February 11th by Thomas & Mercer), is the sequel to last year’s bestselling One Small Sacrifice. NYPD Detective Sheryn Sterling returns with her partner Rafael Mendoza—still recovering from extensive injuries—to investigate a case of blackmail and murder that appears open and shut. When a man is found shot dead in Hell’s Kitchen, the evidence points to a successful young entrepreneur with a troubled past as his killer. But Sheryn can’t let go of small details that don’t add up, and as she follows them, the case becomes far more sinister… and deadly.

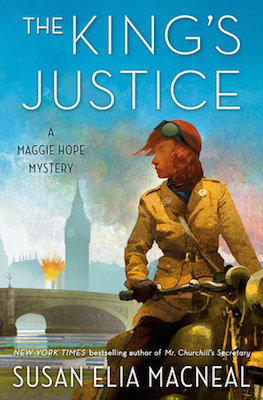

The King’s Justice, Susan Elia MacNeal’s latest, released late last month by Bantam, is the ninth in her New York Times-bestselling  series. This time around her heroine, spy Maggie Hope, is back in London in March of 1943. Reassigned from her duties, she’s put to task helping to defuse bombs in London, when two seemingly separate cases pull her in—a theft of a one-of-a kind violin and a serial killer on the loose. Suffering in ways she won’t admit, Maggie is a bomb waiting to go off herself, and as her investigations progress she’s pitted against a different kind of evil—as well as former enemies.

series. This time around her heroine, spy Maggie Hope, is back in London in March of 1943. Reassigned from her duties, she’s put to task helping to defuse bombs in London, when two seemingly separate cases pull her in—a theft of a one-of-a kind violin and a serial killer on the loose. Suffering in ways she won’t admit, Maggie is a bomb waiting to go off herself, and as her investigations progress she’s pitted against a different kind of evil—as well as former enemies.

Hilary Davidson: I’ve been reading your wonderful Maggie Hope series since the very beginning, when you published Mr. Churchill’s Secretary in 2012. The King’s Justice is the ninth book in the series, and while I was reading it, I realized that it was the first time I’d thought seriously about the toll of everything Maggie has been through. It’s not that you haven’t dealt with pain and trauma before in the series, but it felt like Maggie always managed to compartmentalize those losses. In the latest book, it felt like the bill for all of those “keep going, deal with it later moments” had come due. Did you have a reckoning in mind when you were writing the book?

Susan Elia MacNeal: Yes! In The King’s Justice, Maggie definitely has a reckoning with her past and all the traumas she’s endured. In a way, her journey parallels London’s—the Blitz is over (at least for now, in the winter/spring of 1943). Londoners are coming to terms with the damage and destruction the war has wrought on its people and city. But while the bombing has (mostly) stopped, there are all of the UXBs—Unexploded Bombs—all over the city, which may or may not explode and which have to be detonated. Maggie’s working on defusing the bombs, even as she’s a bit of a UXB herself.

When I read Don’t Look Down, the second novel in your wonderful Shadows of New York series, I was stuck by how much your character Jo Greaver and Maggie have in common. Jo’s also experienced more than her share of trauma—and has done a great job of burying it. But when she gets shot and is accused of murder—her life explodes—and she has to face what’s in her past. I think in both novels, there’s a sort of inevitability in our heroines’ reckonings. What made you decide to not only have Jo come to grips with all of the lies and cover-ups of her past, but all her buried emotions? And what research did you do on PTSD and trauma?

Davidson: My first job out of college was at a government office that served veterans, and one day a vet came in intending to kill everyone there. He started a fire that destroyed three floors of the building. I was lucky to get out uninjured, but afterwards I had panic attacks and felt like I was going to be attacked when I left the house. At the time, I didn’t understand that it was PTSD; it was my secret shame. Dealing with it meant being honest about it, and I published an essay in 2014 about my experience. After that, I wanted to explore PTSD in fiction, and I wrote about it in depth in my last book, One Small Sacrifice. That expanded my understanding of PTSD. I had associated it with life-and-death violence, but I came to realize there are many survivors of sexual abuse who suffer from it as well. As a society, we’re not very good at identifying it when it’s not from a war zone. The character of Jo was informed by that research—her claustrophobia, for example, is far more common for a sexual-abuse survivor with PTSD than a soldier, even if her tendency to self-medicate with alcohol is a common strategy.

I know from my own experience how hard it is to talk about PTSD. Jo was trafficked as a teen, so that created a whole other set of reasons for her to bury her trauma. She’s constructed a life that looks great from the outside, but she’s never able to drop her facade. Putting her in an extreme situation—being blackmailed and getting shot—felt like the only way to unravel her past. Otherwise, Jo would be running from her trauma forever.

I kept seeing parallels between Jo and Maggie, too. Maggie has embraced this image of herself as “the Bomb Girl”—this devil-may-care young woman smoking a cigarette while straddling a bomb she’s just defused. But even while she’s embracing risky behavior, like joining the “Suicide Squad” and driving her motorcycle while tipsy on cider, I kept noticing how tender she is with other characters who’ve suffered trauma. It’s as if she can see their wounds, but not her own. It made me feel like writing this book must have been a tough balancing act. Was it?

MacNeal: Writing this book was tough in so many ways. I wrote before, during, and after the death of my mother, my father’s dementia, and his going into assisted living. I examined a lot of my own personal PTSD, from physical and emotional abuse. But I never felt Maggie’s tenderness was a balancing act. I think it’s possible to self-medicate (because that’s what she’s really doing) and simultaneously care for, and be kind to, other people. And people who’ve experienced trauma recognize others who’ve experienced it. But Maggie is gentle only up to a point—when her friend Chuck is threatened, for example, Maggie’s ready to raise hell on her behalf.

I think that’s one of the ways Jo is different from Maggie. Maggie’s letting it all hang out in this book (so to speak) and really doesn’t give a fork anymore (to quote the great Eleanor Shelstrop from The Good Place)—but Jo has a very carefully crafted persona of a “successful” person. In some ways, I think keeping up the facade must be even harder. What was it like writing Jo when the events of the novel forced her to confront her past? As the author (and someone who also has PTSD) did you not want to go to those dark places? Or was it cathartic to do it through fiction?

Davidson: It’s been cathartic. I think the fact that the source of Jo’s trauma is so different from mine gave me enough distance that it wasn’t painful. She ends up having no choice but to face her past, but that helps free her in a way. When you’re alone with your secrets—as she is—they loom large; telling them to another person shrinks them down to size. The hardest thing, for Jo, was admitting that she had been a victim; in her mind, she’s a survivor, and it doesn’t occur to her that you can be both.

If I’m being completely honest, the hardest part of the book to write was from NYPD Detective Sheryn Sterling’s POV, when she was trying to get people out of a burning building. I think it’s the only time that I’ve felt physically ill while writing a scene. Describing the smell was what got to me. Has that ever happened to you? You write about London so vividly—just as you’ve made other settings come alive in the series—but does the fact we’re decades removed from it make it easier to represent the dread and exhaustion of deep wartime? Or is it painfully vivid in your mind as you write? I’m so curious about how you research the setting and era, too.

MacNeal: The smell. Yes. Just mentioning “burning building” and “the smell” just brought back the events of September 11 and the aftermath so vividly. I think if I’m able to write about London vividly, it’s because of being a New York and living through 9/11. It’s always painful to write, especially seeing democracies weaken around the world and seeing the rise of authoritarian leaders. I mostly watch documentaries, read first person accounts, and talk to people who lived in London during the war (there are fewer now). For all of the facts that books have, someone saying, “I hated the tiny, slimy, slivers of soap we would have to make do with!” give me a detail that resonates in fiction, to bring things home to the reader.

Speaking of Detective Sheryn Sterling (whom I love), she’s got some PTSD, too. It’s different from Jo Greaver’s, but there nonetheless. How did you go about crafting her trauma and her story?

Davidson: There’s so much trauma that’s repressed in cop culture. It’s traditionally written about with gallows humor and treated with self-medication, but the reality is pretty grim. Sheryn is from a military family with a tradition of service, and her father was a veteran who suffered from untreated PTSD. Sheryn is heroic in so many ways, but her work as a homicide detective takes a toll, and it’s cumulative. I should add this is also true of her NYPD partner, Rafael Mendoza, whose physical injuries from the last book carried into this one, as did some psychological trauma from an even earlier case.

There’s also trauma inflicted by racism. Sheryn is African American and her 14-year-old son is arrested at a nonviolent protest. I think with the current conversation around “stop and frisk,” some people are starting to clue in to the trauma inflicted on black and brown people on a daily basis. I just got a very angry review on Amazon from a guy who screamed, “LEAVE THE SOCIAL COMMENTARY OUT OF THE MYSTERY.” Do you ever get reactions like that? Or does writing about an earlier era political commentary safer territory?

MacNeal: I get comments like that, too, sadly. The thing is, these are things that keep repeating in history—so the politics were there in that era, too. But people bring a lot of their own stuff to a book when they read. I don’t take it personally.

One thing that Sheryn says is regard to trauma is “One of the bravest things you can do in your life is to keep moving forward under the weight of that burden,” Sterling said. “You don’t get to put it aside. It’s going to be with you every day, and you’re going to have to figure out how to cope with it.” Damn—that is wise and beautiful. Can you tell me how you wrote that line?

Davidson: Thank you. That really came from the heart. I think there might be an echo of my grandmother in it. She was Irish and full of sayings, and one of them was, “God fits the back for the burden”—meaning that you are always strong enough to cope with whatever happens. My take on that is maybe a bit less optimistic, in that coping with trauma will always be work, and some days that burden will feel extra heavy. But I think there is comfort in knowing that it’s a struggle for everyone.

Now let me quote a line of Maggie’s that hit me hard: “People are confusing and frustrating, flawed and weak. Always confounding. Yet sometimes capable of moments of unexpected grace.” I think it sums up humanity pretty well. How much of that is Maggie, and how much of that is you?

MacNeal: I love that that’s from your grandmother. She’d be so proud, I think. Yeah, so that’s a lot of me in that quote…. I went through a crazy big trauma of my own in the past years (ahem, why THE KING’S JUSTICE took a little more time than usual…). And one of the things I learned is that people you love and count on sometimes don’t show up. And that’s OK—they have their own lives and traumas. And then people you don’t even expect can sometimes shower you with love in such a huge, warm, embracing way. I guess I’ve chosen to understand and forgive people (including myself) for being human and having feet of clay—and focus instead on our flashing, shining moments of grace.