Historical novelists are often asked to choose sides. Are we guardians of the record, charged with preserving facts as they appear in archives and footnotes? Or are we storytellers first, obligated to shape the past into something emotionally legible for modern readers—even if that requires invention, compression, or speculation?

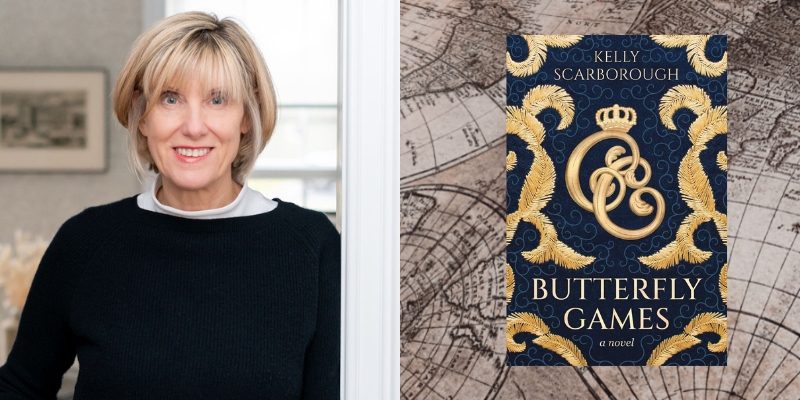

The question is usually framed as binary: accuracy versus imagination. But after spending more than a few years writing Butterfly Games, a novel inspired by the life of Swedish countess Jacquette Gyldenstolpe, I’ve come to believe the question itself is flawed. Historical fiction does not succeed by choosing one side over the other. It succeeds by understanding precisely what kind of truth it is trying to tell.

History gives us fragments. Fiction gives us continuity. The novelist’s task is not to falsify the past, but to interpret it—responsibly, transparently, and with humility about what cannot be known.

The Problem with “Accuracy”

The word accuracy suggests something fixed and verifiable. Dates. Locations. Titles. Who was where, and when. Those details matter enormously, and I treat them as guardrails rather than suggestions. In Butterfly Games, the movements of real historical figures—Prince Oscar, Crown Prince Charles Jean (Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte), Queen Charlotte, Carl Löwenhielm—align closely with what is documented. When characters appear in Stockholm, Drottningholm, or Finspång, it is because the record places them there or at least makes their presence plausible.

But accuracy, in the narrow sense, only takes us so far.

The deeper problem is that the historical record is not neutral. It reflects what was preserved, what was destroyed, and—most critically—whose lives were deemed worth recording in the first place. When writing about women in proximity to the seats of power in the early nineteenth century, the archive often goes quiet just when the story becomes most interesting.

There are no surviving letters between Jacquette Gyldenstolpe and Prince Oscar. There are no eyewitness accounts of their private encounters. Sweden’s famously meticulous archives offer silence where the historical novelist would most want clarity. What remains are hints: letters that skirt the hard questions facing Jacquette, memoirs composed decades later, gossip preserved secondhand, and persistent rumors about her relationship with Prince Oscar.

Faced with these erasures, a writer has three options: abandon the story, reduce it to the known facts, or imagine what might have happened between the documented moments. Historical fiction exists because writers choose the third path.

As Hilary Mantel observed in her BBC Reith Lectures, history is “the record of what’s left on the record.” Fiction begins where the record stops—not to contradict it, but to animate it.

*

Dramatic License as Interpretation, Not Decoration

Dramatic license is often misunderstood as indulgence: adding romance, intrigue, or scandal to make a story “more exciting.” Used that way, it can cheapen both history and fiction. But dramatic license can also function as a form of interpretation—a way of testing what the known facts might mean when placed inside a story.

In Butterfly Games, every conversation between Jacquette and Oscar is invented. Their thoughts, fears, desires, and arguments are imagined. This is not because I believed the truth was unimportant, but because the truth is unknowable. The novel does not claim to reveal what did happen between them. It explores what could have happened, given what we know about their circumstances, personalities, and constraints.

That distinction matters.

Similarly, I made deliberate choices to alter or compress certain elements of the historical record. I changed some names to reduce confusion for readers unfamiliar with Swedish history. I anglicized others. In a few cases, I placed characters together at moments where the record makes their presence unlikely but not impossible.

These decisions were not made casually. Each one was weighed against a central question: Does this change distort the historical reality, or does it clarify it?

Sometimes, clarity requires deviation. A novel crowded with half a dozen men named Carl or Charles may be more “accurate,” but it is less respectful of the reader’s experience. Fiction demands coherence. History rarely provides it.

*

The Ethics of Speculation

The most controversial form of dramatic license involves speculation about motive, intent, and guilt—especially when real people are involved. In Butterfly Games, I depict political intrigue, surveillance, and suspicion at the Swedish court during the fragile early years of the Bernadotte dynasty. Some of these elements are grounded in documented tensions. Others—such as certain conspiracies or personal manipulations—are fictional.

Here, transparency is critical. I do not present these created stories as discoveries. They are offered as possibilities, clearly framed as fiction. In the novel’s historical note, I explain where and why I departed from the record, and where the evidence simply runs out. That note is not an apology; it is an invitation to readers to understand the boundary between history and imagination.

This is especially important when working in a genre adjacent to government and political intrigue. Readers deserve to know when a novelist is extrapolating rather than asserting. Trust, once broken, is difficult to regain.

*

Emotional Truth and the Cost of Silence

If historical accuracy concerns itself with what can be proven, dramatic license concerns itself with what can be felt. The emotional lives of historical figures—particularly women—are often absent from official accounts. Yet emotion shapes decisions as powerfully as policy.

Jacquette Gyldenstolpe appears in the historical record largely as a problem: a young woman rumored to have loved a prince. Her existence did not fit dynastic needs. Her interior life is undocumented. Fiction allows us to ask what it cost her to live under constant scrutiny, with limited agency, in a world where men made the rules and women paid the price for breaking them.

This, to me, is where dramatic license earns its keep. Not in sensationalism, but in restoration. By imagining Jacquette’s fears, desires, and miscalculations, the novel attempts to give back what history took away: complexity.

*

So Which Takes Precedence?

When writing historical fiction, neither accuracy nor dramatic license should take precedence in isolation. Accuracy provides the discipline that keeps a story honest. Dramatic license provides the empathy that makes it readable.

What must take precedence is awareness.

Every deviation from the record should serve a purpose beyond convenience. Every invented scene should be rooted in the constraints of its time. And every reader should be able to trust that the novelist knows the difference between what is documented, what is disputed, and what is imagined.

Historical fiction is not history with better dialogue. It is an act of translation—rendering the past in emotional terms that modern readers can understand without erasing its strangeness or its limits.

When done well, it does not replace the historical record. It sends readers back to it, newly curious, newly skeptical, and newly aware of how much has been lost to silence.

That, I believe, is the real precedence: not accuracy over drama, or drama over accuracy—but respect for both.

***

About Kelly Scarborough