At the Civil War’s end, under a quarter of Americans lived in cities; by the end of the Great War, the proportion was almost exactly half. All those people moving to the cities—both from rural America and from abroad— changed things. Size created anonymity, the possibility of losing yourself in the crowds, remaking yourself, if you so chose. . . . or getting lost, and not always by your choice. Increasingly, the streets were lit by electric light, and the machines inside them were powered the same way; but that simply swapped a new set of shadows and terrors for the old ones. The horrors of the next decades were, all too frequently, industrial and mass-produced: whether they came from the chatter of guns or the whirr of a film projector, they cast an eye on progress, and murmured about what lay beneath.

Start, perhaps, with that newly electrified white city, Chicago. In 1893, its World’s Columbian Exposition, or World’s Fair, was an announcement of America’s newly flexing muscles: its willingness to be broad-shouldered, to play a leadership role in world affairs, to stride into the future. And yet, inside the city limits, there sat a haunted castle. This castle, though, had no clanking chains, no Gothic ghost or Salem witch; it had a psychopath who used modern tools—the soundproofed room, the knockout gas-bearing pipes, and of course, the three-thousand-degrees-Fahrenheit kiln—to disable, kill, and dispose of guests who checked into his World’s Fair Hotel at 701 Sixty-third Street. And why did H. H. Holmes do it? For his part, when eventually caught, he had a simple, and chillingly modern, explanation: “I was born with the devil in me. I could not help the fact that I was a murderer, no more than the poet can help the inspiration to sing.”1

Others, looking at his case, attempted to provide the scrim of moralistic drama. “How the Evil One must glory in the possession of such subjects as H.H. Holmes!” says an 1890s pamphlet Holmes, the Arch Fiend, or a Carnival of Crime.2 But ultimately most of those who spread his story, were less interested in such lessons as in the visceral impact of reporting true life horror. While Holmes was disposing of his victims, after all, Chicago journalists had formed a Whitechapel Club, whose headquarters had a coffin for a bar and was decorated in skulls, a noose, and a blood-caked blanket.3 This sensibility—that horror reported in realistic terms was the height of contemporary aesthetic ambition—was an inheritance of Bierce’s journalism, and Twain’s; and it infused the current wave of literature as well.

One of the period’s great literary creations, a young protagonist named Maggie, didn’t end her days in anything like H. H. Holmes’s murder castle. But the point of Maggie: A Girl of the Streets is that she didn’t need to in order for it to still be a horror story. The novel’s author, Stephen Crane, was a youthful prodigy who wrote his share of Biercean-type horror-of–Civil War stories;4 one, “The Upturned Face,” features the indelible image of a burial in which everything is covered but “the chalk-blue face.” (“Good God,” a character shouts, “Why didn’t you turn him somehow when you put him in?”) But Crane was born six years after the war ended, and the Chicago Inter Ocean’s complaint in 1895, that Crane “doesn’t tell things as a soldier would, and he doesn’t see things as a soldier did, and will make the real soldier tired to follow him,” had some merit to it. And so he turned to the tale of a girl who “blossomed in a mud puddle [and] grew to be a most rare and wonderful production of a tenement district, a pretty girl”; and met a terrifying end, all the more terrifying because it happened every day: Maggie is ruined by her demonic, diabolic wrong guy, in a seduction novel for the American industrial age. By the next year, the Inter Ocean was striking a very different tune, writing that “The dens of woe—called the ‘homes of the poor’—in great cities were never pictured with more horror than in Stephen Crane’s ‘Maggie’. . . . the story is one that will shock the refined reader by its reality, and will sadden any lover of the race that such things should be even a small part of our boasted civilization.”5

___________________________________

___________________________________

Maggie: A Girl of the Streets is about not just the girl, but the streets: “Hell” is a word often used in the novel, and the tenements, with their overcrowded, unsanitary conditions, were portrayed as infernal. And not just by naturalist fiction writers like Crane. Perhaps the chronicler with the most impact was the photographer/writer Jacob Riis, who chronicled the horror of the tenements and displayed them to audiences in two-hour magic-lantern slide lectures on tours throughout the country, one hundred images a tour, dozens of them every year in the first decade of the century. When you saw a photograph with the simple, brutal caption “Slept in that cellar four years”—a horror story in six words—what else could be evoked besides sympathy? Well, fear, of course; fear of what images were coming next in the show, that rumors and reports they’d heard and read of—ranging from white slavery to organized crime—would be next on the docket.6

But perhaps the most omnipresent horror, in those first decades of the century, was the explosion of an industrial capitalism that chewed up waves of workers, Hawthorne’s Notebooks on steam-engine steroids. In 1876’s Edith Hawthorne, or, The Temptations of a Factory Girl, the narrator asks the novel’s reader:

“[R]eader, did you ever examine the texture of the fabric of which your dress is made? . . . When they tremble not with a sigh they vibrate with a groan . . . That beautiful crimson spot you so much admire you think was designed, but the little crushed fingers caught in the ruthless maw of the loom can tell you a different story could they speak.”7

Horror stories abounded. Sometimes they bled into metaphor: in a story appearing in the Ladies’ Garment Worker during the 1910 strike period, “The Living Skeleton and the Stout Reformer,” the Skeleton in question acts as an uncanny guide to a reform-curious owner, convincing him to reform his workplace so as to avoid the spread of consumption in the unsanitary environs. (The wasting consumption, after all, is what had turned him into the living skeleton in the first place).8 But not all employers, to put it mildly, were as forward-looking as the fictional ones devoutly hoped for by the Garment Worker, and not all the stories needed fictional fears to send shudders down workers’ and readers’ spine. Consider, for example, the owners of the Triangle Waist Company, who, like many of their fellow employers, had locked the exits from the factory floor to prevent any breaks or respite—leading to 146 deaths when a fire broke out. Some jumped from ninth-floor windows to their death in order to avoid the flames.

Many of those workers were among the newest Americans—Italian and Jewish immigrants. America was in a massive period of immigration, which led to a corresponding explosion of anti-immigrant sentiment. We’ve seen that fear pervade San Francisco, where white residents’ sense of Yellow Peril manifested itself in discrimination, legislation, and violence; it also suggested itself in a stereotypical association of Orientalism and yellowness as the substance of a kind of deliquescent, decadent fear. We saw this sensibility, a bit, in the “Yellow Wallpaper,” remember; and though Gilman doesn’t mention anything directly racial in the story, it’s worth noting Gilman lived in California while writing the story and would later oppose open immigration. She wrote in 1900, for example, that “the Chinese and the Hindu [were] not races of free and progressive thought and healthy activity,” and that Chinatown was replete with “criminal conditions.”9

But the kind of fear of foreignness we saw in Emma Frances Dawson’s work began to play itself out even more strongly in a kind of Orientalism that, for example, infused what we might call a kind of antiquarian imperialism: the idea that materials brought from people and things far away would have deleterious effects on “good old Americans,” in the same way that—repugnantly—racists argued the new groups of immigrants had a deleterious impact on American society. The English novelist Sax Rohmer’s contemporary take on the subject, The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu, was published in America under the title The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu, and that adjectival shift says everything about the way American fears of the immigrant “other” worked in this period. The description, from Rohmer’s novel, of that “yellow peril incarnate in one man”: “tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan.”10

Perhaps the most important work in this vein, connecting yellowness, foreignness, and evil, was Robert Chambers’s 1895 The King in Yellow— which is the name both of the book of short stories Chambers published, and the hideous tome described in several of those stories that serves as its central binding force. Wilde’s Dorian Gray, published a few years earlier, featured a “yellow book” which was “a poisonous book. The heavy odour of incense seemed to cling about its pages and to trouble the brain,” and Chambers’s book-within-a-book creates madness and death for anyone who encounters it: it’s the predecessor of many, many cursed books to come, but also suggests just how dangerous literature can be. Chambers’s work has a kind of Machenesque ring, with the book as a kind of gateway to a cosmically wide world, from which hideous forces sometimes cross over to ours. Indeed, in one of the stories in Chambers’s book, we hear the devil-King cite scripture for his purpose: “It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God!” he whispers to the narrator, as the latter falls into perdition.11

But as frightening as the accounts of that descent can be—and Chambers’s signature story, “The Repairer of Reputations,” pulls this off excellently—what truly disturbs is the future world in which the story is set: a dystopian utopia, a quarter-century in the future, whose tranquility has been purchased at the expense of keeping out Jewish immigrants “as a measure of national self-preservation” and ethnically cleansing Black people to “the new independent negro state of Suwanee,” alongside other anti-immigrant laws.12 The rot that thus lurks at the heart of a society focused on racial and ethnic superficialities is concretized, both through the Government Lethal Chambers that dot the cities (for all the suicides, you see), and the career of the repairer of reputations—to say nothing of the rotting King in Yellow tome that circulates through the book, and the world. The story leaves open the possibility that all of this exists in the narrator’s head, a head that has been recently and severely injured, as fevered racist images all too often do. But, nonetheless—and this is part of the horror, too—it’s a world real enough in his head to lead to at least one murder.

But you didn’t have to be coming from abroad to be a source of, and a victim of, white fear. In the Atlantic, Zitkála-Ša, of the Yankton Dakota tribe (then largely known as the Sioux), wrote a series of quasi-autobiographical sketches in 1900 that satisfied that magazine’s readers’ interest in Native life, but simultaneously damningly indicted what their government had done to them in the process of creating the kind of person who might write about it for the Atlantic.13 In her work “The School Days of an Indian Girl,” she evocatively gives a picture of the “white man’s devil” she sees in an illustrated Christian Bible, who—in a nightmare she has—chases her while ignoring her Native mother and a visiting friend, because “he did not know the Indian language.” It’s only her mother’s embrace that awakens and saves her; the diabolic intervention of an education and acculturation that attempts to distance her from her roots is literally the stuff of nightmares.14

For her part, Pauline Hopkins, a Black writer and editor, chose to play out her own narratives of fear, frustration at the glacial pace of progress toward racial equality, and fantastic, imaginative possibility for catharsis, in the magazine where she served as literary editor. The Colored American Magazine, published in Boston in the new century’s first decade, was inspired by mass-market magazines like McClure’s and Cosmopolitan alongside the Atlantic and Harper’s.15 In 1902–1903, Hopkins published her novel Of One Blood there, which picked up on Chesnutt’s fraught tales of the color line: the novel features two biracial characters whose romance is initially frustrated by their desire or need to keep their respective heritages secret. But, unlike Chesnutt’s tale, Hopkins’s novel gives way to a story of African kingdoms and a rich cultural inheritance, with its fantastic ending serving as “the construction of a fictional alternative to the limitations of national identity.”16 “What would the professors of Harvard have said to this,” the main character asks himself, coming face to face with the inheritance he is rightfully vouchsafed. “In the heart of Africa was a knowledge of science that all the wealth and learning of modern times could not emulate.”17

Both Hopkins’s and Chambers’s work was, in a sense, about discovery— of the possibilities and fears of intellectual exploration, of colonialist exploration, of worlds beyond those that were imagined; and these worlds were now available to an increasingly wide range of readers in the form of cheap paper and ink. The magazines our previous horror fiction had appeared in—the Atlantic, Harper’s, and the like—weren’t just high-brow but highcost: the waves of immigrants, and their children, were in the market for lower-priced stuff. Newspapers obliged, and the melodramatic, sensationalist turn of publishers like Joseph Pulitzer—the “if it bleeds, it leads” philosophy he espoused—made its way into news stories that obsessed the public. Sometimes they were exposés of terrors of corruption, like Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper’s look at the tainted milk business—which warned “the squeamish and the prudish” not to read, and then offered “a record of unimpeachable facts, unutterably abominable, but true,” laid out in vivid detail, augmented by the illustrations of editorial-cartooning pioneer Thomas Nast.18 Sometimes, it was the gaping, voyeuristic horror that marked the reportage about disasters like the San Francisco earthquake, lingering over the devastation and the wreck: ALL SAN FRANCISCO MAY BURN, read the A1 headline in the New York Times, 19 and one might just detect an attraction to the flame beneath the genuine horror and concern that undoubtedly also drew readers. Pulitzer and Hearst wanted to inform their readers; but they also wanted their pennies and nickels, and they’d give column inches and blaring headlines to the stories that filled their coffers.

And so the front pages were often dominated by lurid true-crime horror that made celebrity monsters, and monster celebrities. As Holmes was committing his murders in secret, for example, Lizzie Borden of Fall River, Massachusetts, as the folk song would soon have it, “took an axe / and gave her mother forty whacks / When she saw what she had done, / She gave her father forty-one.” To be scrupulously honest, it was her stepmother, and it was less than three dozen blows for the two of them, and Borden was acquitted, after fainting in court when the skulls of the murdered pair were presented in the court as evidence. But the legend was printed, in the newspapers mushrooming around the country. And such accounts could be provided in remarkably gory detail. Lafcadio Hearn, reporting on a notorious Cincinnati murder in 1874, described “a hideous adhesion of half-molten flesh, boiled brains, and jellied blood mingled with coal.” The skull, discovered after some time in a furnace, presumably placed there to dispose of the evidence, had “burst like a shell in the fierce furnace-heat; and the whole upper portion seemed as though it had been blown out by the steam of the boiling and bubbling brains.” Which he then touched, reporting it the “consistency of banana fruit.”20

But that was old news, nineteenth-century news; the new crime of the new century was the notorious murder of Stanford White by Harry Thaw. The trial had everything you could possibly want in it: there was model and showgirl Evelyn Nesbit’s relationship with famed architect Stanford White, which may or may not have involved moral corruption. (Nesbit, the young woman involved in the fatal love triangle, testified how, as a teenager, White would push her on a red velvet swing in his apartment, she wearing nothing but the jewelry he’d given her.) There was the young railroad heir Thaw, obsessive in his desire for Nesbit, finally convincing her to marry him. There was the murder itself, borne of jealousy and mental instability, and occurring during the finale of a rooftop show at Madison Square Garden. The newspapers ran with it for months, through the “trial of the century” in early 1907, salivating over the corruption of youth with the same impulse that Henry James had had, the decade before, though now with quite different methods.21

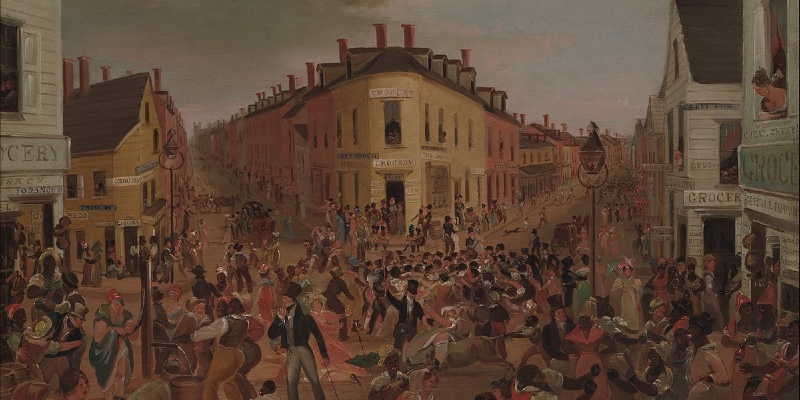

Of course, New York had been considered an “evil city” before, throughout the nineteenth century, in novels like Osgood Bradbury’s The Belle of the Bowery (1846), George Thompson’s City Crimes: Or, Life in New York and Boston (1849), and Edward Z. C. Judson’s The B’Hoys of New York: A Sequel to the Mysteries & Miseries of New York (1849). Joaquinn Miller’s The Destruction of Gotham (1886) even featured “a violent apocalyptic vision of the burning of New York . . .brought about by a sudden release of all the terrible energies of evil abroad in Gotham.” There were “an assortment of illustrated subscription books ‘devoted to telling the truth’ about Manhattan” that offered “an oftentimes lurid picture to thousands of the unsophisticated who purchased them from itinerant book agents.”22 One particularly vivid contemporary example was Junius Henry Browne’s 700- page The Great Metropolis: A Mirror of New York, with its tales of thousands of robbers, pickpockets, and thieves; prostitutes galore; and crooked adoption agents who weren’t so picky about where they got their children from.

But a new menace was emerging, beginning to dot the streets and alleys of the city, a tidal wave that threatened to render practically obsolete everything that came before it, one that brought horrors to the world more stunningly than ever before. And you wouldn’t have to risk your neck to seek it out, either. All you needed was a nickel to see it; and all they needed to show it to you was a flat surface, and a film projector.

___________________________________