Ah, the winter holiday season. The most wonderful time of the year—or is it?

Most merry readers are familiar with ye olde traditions of telling ghost stories at Christmastime. While many believe this to be a primarily English holiday pastime—with Victorian-era celebrants gathered around the hearth to while away winter nights in the company of ghost stories and séances—this isn’t completely true. In fact, though the Puritanical culture of early America was, shall we say, less than hospitable to such things as spirits and hauntings, there is a distinctly American flavor to the heart-warming tradition of horrifying your friends and family with tales of monsters, malice, and malevolent spirits during the holidays.

And that distinctly American flavor? Sleepy Hollow’s own Washington Irving—yes, that Washington Irving.

As fellow horror author Grady Hendrix points out in his article “Christmas Ghost Stories: How the Holidays Became Haunted,” our earliest published proto-Christmas ghost story belongs to Manhattan-born Washington Irving. Published in 1819, Irving’s The Sketch Book contains a collection of essays and short stories praising traditional customs and parodying modern manners, including a series of Christmas essays describing vast country feasts and ghost stories told ‘round the fire. It should come as no surprise, then, that The Sketch Book culminates with “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”

Sure, the timeline between Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1843) and Irving’s The Sketch Book (1819) is a bit of a Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) versus Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872) squabble (though the Hudson Valley Historic District, home to bucolic Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, where Irving now rests, has a lot to say about it), and sure, Irving did live briefly in England and was undoubtedly influenced by the English traditions of Christmastime ghouls (Irving did a stint working the family business in the UK, where he penned the essays and stories in The Sketch Book). However, while “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” has become almost synonymous with American Halloween traditions, Irving’s Headless Horseman has nonetheless had a profound impact on the tradition of winter holiday hauntings at home as well.

Regardless, whether it’s Irving or Dickens, these chilling tales share a common thread: crimes and consequences. And the biggest crime committed by both Ebenezer Scrooge and Ichabod Crane? Loneliness.

“There is nothing like the silence and loneliness of night to bring dark shadows over the brightest mind,” writes Irving about his easily spooked pedagogue. But while Ichabod Crane surely suffered from loneliness, Charles Dickens’s Ebeneezer Scrooge is perhaps the most classic example of being terrorized for the existential crime of un-merriment. As Darren Anderson notes in his incredibly illuminating article “Britain is Haunted by Dickensian Ghosts,” Scrooge’s damnation is personal: he is miserly, greedy, and marginalized—a stand-in for deeper explorations of heavier themes that surrounded the economics and social mores of nineteenth-century London.

As a “social tract and fable,” Dickens’s A Christmas Carol is evergreen in that these mores—poverty, homelessness, generalized anxiety and despair—are no less relevant in today’s world. Perhaps they are even more present, an ironic twist for old Ebenezer. In 2017, the Jo Cox Commission stated that nine million people in the UK were stricken by loneliness. In 2019, a YouGov survey showed that 18% off men did not have a close friend, and 32% without anyone they considered a best friend. Women fared marginally better, at 12% and 24%, respectively. Of course, loneliness, like holiday ghost stories, isn’t a purely UK phenomenon: in an early 2024 Healthy Minds Monthly Poll by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), 30% of US adults say they have experienced loneliness at least once a week, while 10% say they are lonely every day.

For those lonely and unmerry, hauntings become almost inevitable, something both Irving and Dickens knew too well. Per Anderson, “Victorian writers knew that when we are alone at Christmas, a time that seems intrinsically meant for loved ones congregating, our ghosts, borne by memory, absence and regret, would instead arrive.” Indeed, they do, manifesting in horrors that are often retribution for the crime of un-merriment committed by the story’s protagonists. Horror, then, is the consequence of murder, avarice, poverty, etc., but the crime itself is in what preceded it (adultery, alcoholism, abuse, mental illness, old age), typically borne of loneliness and often pushed to the point of insanity. The two do share space, after all, with loneliness associated with a number of mental health issues: hallucinations, paranoid thinking, depression, anxiety, substance abuse—all fertile breeding ground for monsters and the monstrous.

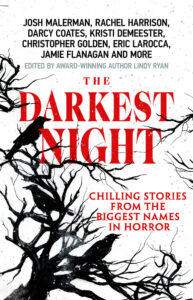

Today, horrifying holiday tales still operate in the liminal spaces of criminalized loneliness, and the stories in The Darkest Night continue this hallowed tradition. Take for example, Hailey Piper’s “The Vermin Moon,” wherein a mother grieving her deceased daughter summons old magic, or Jamie Flanagan’s “Bruiser,” where a nurse comforts a dying man whose attempts at memorial are thwarted at winter, or Mercedes M. Yardley’s “Ghosted,” as a haunted widow sets herself free of her husband’s ghost at Christmas. Monsters can be quite literal, as in Christopher Golden and Tim Lebbon’s “Wintry Blue,” a wendigo story, or Rachel Harrison’s “Thaw,” as things get bloody for a couple on holiday, or Tim Waggoner’s “Cold as Ice,” where a divorced man joins the Wild Hunt.

There are, of course, stories of murder and revenge, like Thommy Hutson’s “Candy Cane” and Kristi DeMeester’s “Eggnog,” but there are just as often stories of guilt, regret, and mourning that yield terrifying results, such as in “Feast of Gray,” co-written by myself and Christopher Brooks, when a recovering alcoholic visits his mother’s grave and is accosted by the spirit of his own guilt, or Darcy Coates’s “The Ladies’ Society for the Dead,” where a group of women hold a séance to lay to rest wandering spirits of murdered women, or M. Rickert’s “The Buried Child,” a haunting story of generational trauma, and Sara Tantlinger’s “Threads of Epiphany,” when a young woman makes a deal to save her brother. Josh Malerman’s “Children Aren’t the Only Ones Who Know Where the Presents are Hidden” puts childhood trauma on the page, while Eric LaRocca’s “Contrition for an Enchanted Evening” takes a distinctly LaRoccian look at, well, certain horrors of childhood. And speaking of the childish wonder of the holidays, are gifts not without consequences? Nat Cassidy’s “Nice” and Jeff Strand’s “Being Nice” have a thing or two to say about that, as does the horror unboxed in Clay MacLeod Chapman’s “Mr. Butler.”

Oh, and let’s not forget the crucial role women play in holiday hauntings!

In a time when holiday horror tales were quite widespread, crimes of un-merriment and loneliness were levied more heavily against women. Ladies bore the brunt of hauntings: attacked by “deformed idiotic sons” of wealthy families, by their husbands’ identical twins, by vampires, by screaming faces that drove them insane, by escaped lunatics that smothered them all night, etc. Likewise, men were often at the mercy of women and their brood: ghost children lured babies outdoors to freeze to death while men seeking shelter from blizzards in unused nurseries were attacked by disembodied bones and/or goblin babies, and doctors and priests (male-only professions) were haunted by possessed clothes and visited by decapitated lady ghosts.

Beware the woman in white, indeed! And to that end, beware Gwendolyn Kiste’s “The Mouthless Body in the Lake,” as a woman slips inside her frozen double, or Cynthia Pelayo’s “The Warmth of Snow,” a story of winter yearning, or Stephanie M. Wytovich’s blood thirsty “The Body of Leonora James,” or Lee Murray’s vengeful “Father’s Last Christmas,” or Kelsea Yu’s vigilante-justice “Carol of the Hells.”

(By the by, studies show that women still disproportionately experience loneliness around the holidays. The APA reports 44% of women (compared to 31% of men) experience higher stress levels during the season, while only 27% of women say they are able to relax over the holidays (compared to 41% of men).)

Today, the winter holidays continue the long-standing, hallowed tradition of spinning tales of monsters, malice, and malevolent spirits, but if there’s one thing we’ve learned, it’s the importance of finding peace and merriment during these long, cold nights that offer a perfect time for reflection, remembrance, and reckoning for us all.

***