“Good Americans, when they die, go to Paris.” —Oscar Wilde

Fiction, like dreams, is truth in an acceptable disguise. And mysteries are all about disguises, particularly about disguising the truth itself.

Mysteries satisfy us in so many ways, partly because, like dreams, they can bring order to our minds. They speak to our desire for justice, for righting wrongs and setting the world straight. They show us the best and worst of human character. Most of all, though, they’re a lot of fun.

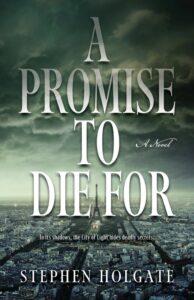

I’m hoping to add to the fun with A Promise to Die For, a suspense thriller set in Paris.

I’ve enjoyed reading countless cozies. But when it comes to writing, I’ve followed a path more like Dashiell Hammett, who said he took murder out of the vicarage and put it in the back alley, where it belongs. In A Promise to Die For you won’t find either the vicarage or the back alley.

In it, Sam Hough promises a dying friend to find his five-year-old son, born out of wedlock, living in Paris. This challenging, yet seemingly innocent promise, quickly leads Sam into a web of mystery, danger, and romance—and the suspicion that his dying friend hadn’t told him everything.

Where do I get off writing a book set in Paris? Oscar Wilde notwithstanding, I got to Paris without dying, and had the great good fortune to know it well.

After a decade of various jobs, mostly in politics, that never quite added up to a career, I fell in with bad companions and ended up a diplomat. After passing the requisite tests, the physical, the security clearance, I entered the foreign service as a Junior Officer Trainee. The title alone tells you how low I stood on the bureaucratic totem pole.

Once sworn in, someone decided the national interest was best served by posting me and my family to the American embassy in Paris. I didn’t argue.

During my time there—and in later visits—I walked the city endlessly, coming to know the city’s ancient, narrow streets and modern broad avenues and its colorful neighborhoods in ways I had never imagined while growing up in Tigard, Oregon.

As a boy in that tiny town of fewer than two thousand souls, I had in fact travelled broadly without leaving the bounds of my neighborhood. The fact that I had done it entirely in books didn’t matter to me. Lounging on our couch or hiding under the blankets at night with a flashlight, by the time I was twelve I had roamed the world, going to Bayport to solve mysteries with the Hardy Boys, voyaging twenty thousand leagues under the sea with Captain Nemo to find the wonders of the ocean, roaming the foggy crooked byways of London with Holmes and Watson to discover the darkness in the human heart. Transported by my wanderings, I made a list of all the places my reading took me and often read it over. I’m proud to say it; I was a nerd.

These vicarious adventures raised in me a desire to lead a globetrotting life of adventure—and to be a writer myself, if only to tell tales of my own adventures.

Life in the foreign service gave my family and me all the travel we could have ever imagined, and adventures far beyond the vicarious. After Paris we were posted to Madagascar, Morocco, Mexico, Sri Lanka. We shared with our embassy colleagues the risks and rewards of this peculiar life. First among those rewards was the privilege of serving our country. Though it may sound corny to some, coming into work I was often stirred by the sight of the American flag flying over the foreign post in which I served.

The two great additional perks were meeting fascinating people and seeing places we had never imagined we would see. And we were allowed to live in cultures vastly different from our own. When we first arrived at these posts, we found the often-profound cultural differences baffling, disorienting, impenetrable. Often, my first question was, “What in the world am I doing here?”

Quickly, though, we started to adapt, stopped resenting change and embraced it. We entered into a truly foreign way of acting, of speaking, of looking at the world. And, in a healthy sort of dual identity, we did it while retaining our own identity. We were all, after all, professionally American, not only by nationality but by trade.

Along with these rewards came the risks. In Madagascar a soldier at a checkpoint pulled back the bolt on his AK-47, aimed it at me, and braced to fire. I’ll never know why he did that or why he didn’t shoot—and I didn’t stick around to quiz him about it. In one post, terrorists targeted the building I worked in. Only the infiltration and arrest of the group by local security services kept them from succeeding. In another post, illness took my 6’3” frame down to 145 pounds. I looked like that picture that goes with the warning on an iodine bottle. In the same post, a fascinating but sometimes perilous place to live, my wife and our son, four-years-old, came down with a deadly form of malaria that almost took their lives. The diplomatic life can look charming and elegant in movies. In reality, it can prove dangerous and stressful.

What does this have to do with writing? Everything.

I would never say that my service to our country, the trials and joys we went through, were simply grist for the mill of my writing. When I retired, though, and we came home to Oregon, I had time to reflect on our experience, to try to make sense of it. I came to feel an obligation to share what I had learned. The best way to do that, I found, was to write. Yes, it was what I had wanted to do since childhood. Now, though, I had what I had lacked: a subject, a firm base to stand on as I wrote.

In previous novels—Tangier, Sri Lanka, and Madagascar—I returned to the places where I had lived and worked, and used them as the settings for my novels, writing stories I believed could only happen in these places, stories of intrigue, suspense, and romance that would bring to readers something of the truth of what these places are about.

The truth. I bring myself back to where I started. And the truth is that these places, these cultures, even my own experiences remain a stubborn mystery, a mystery I pass along to you in my writing.

***