Like a lot of people, I spent the long winter months of lockdown either slouched in my pyjamas in front of the TV, ice cream tub in hand, or in full peppy workout mode, sweating to online fitness classes or pounding out the miles on a treadmill in my garage. Said treadmill was not really designed for that level of use, or, it turns out, for being stored in a cold, slightly damp outbuilding, and by the time the pandemic was over, it was starting to glitch.

I booked a repairman my dad had recommended, who seemed friendly enough. He came to have a look at the treadmill and I showed him through to the garage, chatting about the village and how long I’d lived there, and about the weather, which had just turned warm. He was in his fifties, smiley, polite, and seemed to already have a good idea what was wrong with the machine.

Inside the garage, I stood and watched him take the motor apart, looking for the fault. We were still making small talk, and as he tested a few components, he ran me through my options for repairing or replacing the treadmill. He talked about how expensive parts had become and then, in the same breath, he asked if I knew about the three US asset managers who controlled the world and everything we do. I was confused by the sudden shift in his tone; I said that I didn’t. ‘That’s right,’ he said. ‘They faked 9/11 and that’s how it all started.’

I was starting to get nervous now, because there was something combative in the way he said it, like he was inviting me to disagree with him. I murmured noncommittally, and wondered if I could make my excuses and go back to the house while he finished his work.

‘You know, Ukraine, the war: same thing,’ he said, pointing at me with the screwdriver in his hand. ‘All those photos of bombsites? Faked. They’re doing it.’

He’d stood up now, his body blocking my path to the door.

‘You’re not vaccinated, are you?’ he asked. I was. He didn’t like that. The pandemic, of course, had also been faked.

I wish I could say I’d challenged him, or asked more, tried to understand, but the truth is, I was scared. The way he’d switched, the anger with which he was speaking: it scared me. So I nodded politely, edging away, trying to return the conversation to the treadmill. When he told me couldn’t fix it, I transferred the callout fee as he requested. As we walked back through the house, he offered me some advice: if I was ever arrested by the police, I should tell them I didn’t have a name and didn’t consent to the arrest. And if I ever had children, it was important I didn’t register their birth, because then the state could never take them from me.

And then he was gone, heading out of my front door and into a waiting car – driven by a friend he’d hired to be his chauffeur, since he didn’t want a driving licence of his own and the accompanying records by which the government could claim authority over him.

*

My favourite way to waste time on the internet then was reading AITA threads on Reddit or, even better, Mumsnet’s very British equivalent: AIBU (Am I Being Unreasonable?). It’s usually a hotbed of parking disputes, badly behaved partners and vacation dilemmas. But around the time of the treadmill man, I started to see increasingly frequent posts from people who were worried about friends or family members obsessed with QAnon and other conspiracy theories. In real life, I was noticing something similar. Someone I’d known for years claimed to me one day, entirely seriously, that Joe Biden had died and been replaced by someone wearing a mask. People I’d been to school with were posting conspiracy content on Facebook, including someone who set up his own alternative news livestream each day, giving his unsolicited take on all of the mainstream media’s headlines – and the real stories they were hiding. These were things that would have seemed bizarre, once upon a time, but in the post-pandemic years, it was an increasingly regular occurrence in my life.

In Britain, during Covid we’d locked down and isolated ourselves while the politicians who’d made those rules threw debauched parties in Downing Street. We’d watched the news of missing Sarah Everard unfold, only to hear she had been brutally murdered by a police officer, who falsely arrested her to get her into his car. It’s easy to see how our collective trust in the system, in authority, has been eroded over the recent unprecedented past. And how those cracks, now widening, are allowing conspiracy theories to take root, to gather momentum.

**

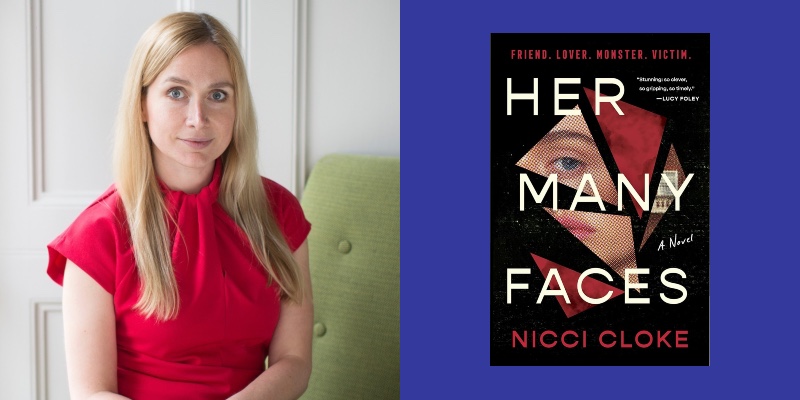

I had already experimented with a couple of iterations of the novel that would become Her Many Faces, the story of a young woman on trial for murdering four powerful, wealthy men. But this experience led me to dig deeper into this new kind of online radicalisation, and how it might have driven a character like mine to the most shocking of action. I watched documentaries, read real-life accounts of people who had been down the rabbit hole, spent hours on forums. I returned to those Reddit and Mumsnet threads too, and saw pages and pages of comments from users who were experiencing the same things – family fractures opening up as one member’s beliefs diverted so far from their own. And if those beliefs centre around the tenet that you can’t trust the news, the government or the legal system, it’s very hard to provide evidence to counter any statement. In the end, users were giving up trying to reason with their loved ones, and simply turning away from them.

I think about the treadmill man sometimes, three years on. I think about how angry he was, but also how afraid he seemed. What it’s like, to live in a world you feel so certain is conspiring against you. I wonder what would happen if he ever ends up on a jury, or on trial. Lately, I’ve been watching the Karen Read case unfold – how easily a courtroom can become a battleground of conspiracy, how quickly public trust frays when every fact has a counter-theory. These days, I’m not sure the line between paranoia and possibility is as clear as we’d like to believe. I’ve deleted my Facebook account, so I’m not sure if those contacts are still posting their alternative news – and I haven’t seen that friend to ask if she still believes Joe Biden is someone in a mask. But if she does, I’m not sure who will be able to persuade her otherwise, or how. It’s her version of the truth now, and opening the door back to ours seemed like an option that was far more frightening for her to consider.

***