If you have ever wanted to know how it feels to snatch a painting from a museum wall, slide it under your shirt, and take off, then Michael Finkel’s, The Art Thief is for you. Finkel puts you in the scene and in the mind of Stephane Breistwieser, a man who stole more than 200 artworks from European museums and churches for a combined worth of $2 billion dollars. Breistwieser loved art, believed he could take care of it better than any museum, never sold a single piece, and lived with it until he couldn’t (a spoiler I will not disclose). At just over two-hundred-pages it’s a concise page-turner, a book for anyone interested in the criminal mind, with all the daring and chutzpah it takes to steal art, a true tale that will thrill you (but hopefully not inspire you)!

You could say I’ve been obsessed with art crime for a long time. Not only because I went to art school and studied painting but because I have been creating forgeries and fakes, exact replicas of famous and semi-famous artworks, for art collectors for the past twenty years. “Legal” fakes and forgeries, that is, a side gig that led me to the study and psychology of art forgers, thieves, and the world of art crime which, after drugs and illegal arms, is the third largest criminal activity in the world (50,000-100,000 works of art stolen annually and only 5-10% ever recovered).

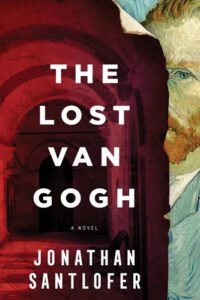

Over the course of my writing career, I’ve interviewed members of the FBI’s Art Crime Team, an inspector from Scotland Yard’s Art and Antiques unit, and even modeled one of my main characters, John Washington Smith, the INTERPOL art analyst in The Lost Van Gogh and The Last Mona Lisa, after a retired INTERPOL analyst who generously shared some of his secrets.

Art crime is a terrific subject, plot twist ready. Who can forget the 1990 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum theft of thirteen artworks, among them Manet, Degas, Vermeer, and Rembrandt, the works savagely cut from their frames, a tragic and expensive loss, $500 million to be exact. It’s unlikely the world will ever see these one-of-a-kind masterpieces again though you can watch the 4-part Netflix documentary This is a Robbery: the World’s Biggest Art Heist, which sheds light on the crime (an inside job? the Irish mob?) but without a solution. Thirty-one years later the Gardner Museum is still offering a $10 million reward, so if you have a lead, call me.

The other books that gripped me this past year were research for my Van Gogh novel, many having to do with Nazi-looted art, the most comprehensive and premeditated art crime program ever perpetrated on humanity, Hitler planning to create his own museum, the Fuhermuseum, a proposed temple to (stolen) art, in his hometown of Linz, Austria. The war ended before he could realize his vision, but not before the Nazis had stolen an estimated one fifth of the art in Europe (more than 5 million paintings and objects, with at least 100,000 still not returned). Behind every one of these looted artworks is (at least) one death, something that separates the Nazis from your run of the mill art thief.

I can’t say it’s fun reading, but compelling and essential to understanding the Nazis’ calculated art plunder, and the fact that the sale of these stolen artworks continues today. Many of the books kept me turning pages in stunned disbelief, while providing facts and data for my novel, which I will never forget. Among the best, Susan Ronald’s Hitler’s Art Thief and two by Jonathan Petropoulos, Goring’s Man in Paris and Faustian Bargain, taken together just about everything you ever wanted to know about Nazi art looting. For a more personal story of one man’s search for his family’s Nazi-looted art, The Orpheus Clock by Simon Goodman, is beautifully told and so heart wrenching it often had me in tears.

A friend who spied my library—shelf after shelf of books on Hitler, Goring, Nazis, and stolen art—suggested I read a romantic comedy. Instead, I watched one, Billy Wilder’s A Foreign Affair, (1948), a Nazi romcom (you heard that right), filmed on location in post-war Berlin with Marlene Dietrich as a cabaret singer and possibly the former mistress of Hermann Göring or Joseph Goebbels. Wilder always said the tougher the material the more you’d better make them laugh, and I agree. Using Nazi art plunder in a thriller was a challenge, I have always believed if you want people to understand something don’t preach, entertain.

I also rewatched one my favorite art heist movies, The Thomas Crown Affair (the 1999 remake) with Pierce Brosnan and the most brilliant, gorgeous, art insurance agent who ever graced the silver screen, Rene Russo’s Catherine Banning (upon whom I based my protagonist, Kate McKinnon, former cop turned art historian in The Death Artist).

After that, I watched Woman in Gold, a top-notch Nazi art-restitution film (based on Anne-Marie O’Connor’s book The Lady in Gold: The Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt’s Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Block-Bauer). With the always brilliant Helen Mirren and Ryan Remolds as her devoted young lawyer battling a belligerent museum—and winning! You can see Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (also called The Lady in Gold) on display at NY’s Neue Galerie.

From there, it was a deep dive into all things Van Gogh. Irving Stone’s 1934 book Lust for Life, and the 1956 movie made from it, both fun and fascinating though filled with inaccuracies. It’s not that I’m against artistic license (I use it all the time) but I think it’s essential to let your readers know what is fact and what is fiction. Still, Kirk Douglas as Van Gogh is worth watching, whether he’s painting or going mad or raging at his artist frenemy Paul Gauguin (a pitch-perfect Anthony Quinn), their super-charged artistic relationship a hairsbreadth away from a full-blown love affair gone bad.

Lust for Life does not deal with the ongoing mystery of Van Gogh’s death—unlike the staggering 800-page-plus biography, Van Gogh, The Life, by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, a fact-filled and engaging book that does delve into the crime surrounding Van Gogh’s death, something I believe and offer up in my novel for readers to decide.

For a movie version of that crime, check out Julian Schnabel’s, At Eternity’s Gate, with Willem Defoe as a credible Van Gogh, and Oscar Isaac as Gauguin. Their scenes together are too few, but artist/filmmaker Schnabel knows how to recreate the act of painting on screen so believably and sensually it will make you want to pick up a paintbrush.

For more Willem Dafoe, there’s Inside, a wildly claustrophobic film about an art thief who gets trapped in the lavish but empty apartment he is trying to rob. It’s a descent into artistic hell Robinson Crusoe style, with graphic scenes of Dafoe foraging for food and drink that border on torture porn. Where’s Friday when you need him? The film’s tag line should read, Art Crime Doesn’t Pay. Not always the case, and clearly, I enjoy putting it on the page.

***