People ask writers about the best piece of advice they ever received. I haven’t received many, but I recall one particularly well.

Many years ago I had a friendly acquaintance with the brilliant writer/producer/director Larry Gelbart, probably best known as having developed M*A*S*H for television and co-written the book for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. He was a real mensch, a gentleman who did not rub his fame in your face. And I asked him once how he could take something that made him very angry and turn it into genius-level comedy, which he often did.

“Go where the pain is,” Gelbart said. It took me a long time to process that and even longer to be able to use it, but it was as valuable a tip as I have ever gotten.

Did he mean I should explore my pain, what was eating at me and making me want to write about it? Or was the advice to go to the character’s pain and, being a sadistic writer, wring as much out of it as possible?

(I could have asked Larry those questions but I didn’t want to seem like an idiot rookie to the master, even if he never would have made me feel that way.)

After much thought I realized it didn’t matter. The character’s pain, even if it came from different circumstances, would be mine because the character came from me. If a writer isn’t empathetic and able to feel the emotions their characters are having, they’re not going to be in the business for long.

So I started looking for where the pain was, and I realized everyone has some pain. Everyone feels insecure and vulnerable about something. Everyone has something about themselves they don’t want others to know, or would at least prefer never came up in conversation.

When I start writing a new character now, I think about where their pain might be and how best to exploit it, because being nice to your characters is a foolproof way to write a very dull story. So the basic concept of the character might be the source of that pain.

It’s not always straightforward like that. Sometimes the character’s pain – and therefore the key to their personality – comes to the writer later, at an unexpected time (usually around Chapter Six). Consider what makes your character sad or angry and why, and you’re on your way to creating a living, breathing human being and not a one-note plot device.

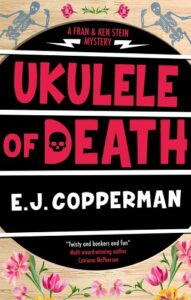

When I started writing UKULELE OF DEATH, the first book in what will be the Fran and Ken Stein Mystery series, I was not looking for my narrator (Fran)’s pain. I had enough to deal with.

It was going to be a fun take on the Mary Wollstonecraft Shelly story (hence, Fran and Ken Stein) about two siblings who have a secret: They were never born. They’re the results of experiments by two brilliant scientists who they consider their parents. But that led to immediate questions the characters would have to consider, and the first was a humdinger.

Am I human?

It’s not an easy question for Fran and Ken. They have USB ports under their left arms to restore their energy through connection to a wall socket, something they have to do every few days. But their minds and emotions are not all that different from those of the average citizen. Are they human?

Now, if that’s not a source of pain for your character I can’t tell you what will be. These are people who are generally indistinguishable from everyone else, other than being larger and stronger than pretty much everybody. But they know how they came to be and they know there are those who would exploit that information. They know they’re targets just for being themselves. Go try not being yourself sometime and see how that works out.

Bingo. I’d found the character’s pain. Now all I needed was a story. So Fran and Ken are searching for a rare ukulele because a client came to their detective agency, which specializes in helping adopted people find their birth parents, saying that finding a particular little Hawaiian guitar can help lead to her birth father. So sure, they’ll help.

Except before they can get a grip on the case their client is murdered and it’s clear someone is coming after Fran and Ken. Will Fran, because she’s telling us the story, be able to deal with all that while wondering about how people look at her? What they see that she might not be willing to share? Whether or not she’s really a person?

It gives me a lot to work with, so thank you, Larry.

***