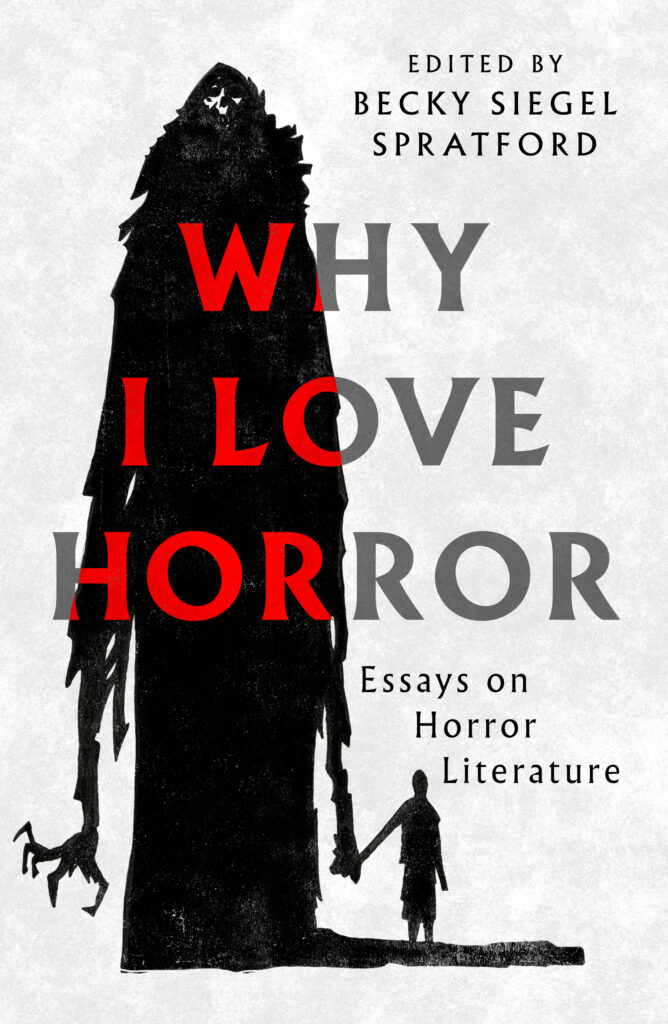

From the introduction to the essay: Grady Hendrix began his career as a horror novelist leaning into parody and humor, but over the years, while he has found ways to continue to incorporate humor, his novels have gotten progressively more serious and darker. Hendrix’s stories feature a strong, often nostalgic sense of place and even stronger female protagonists overcoming dangerous, supernatural events that arise from what readers can easily identify as mundane situations. Another interesting quirk about Hendrix is his insistence on not being pigeonholed. He has stated many times that he goes out of his way to make sure every novel examines a new horror subgenre or trope, thus introducing his legions of fans to the full breadth of the genre’s offerings. Finally, Hendrix is also a proud historian of the 1970s and ’80s era of pulp horror, as demonstrated in his Bram Stoker Award–winning nonfiction survey of the era, Paperbacks from Hell.

I opened my dad’s freezer and found a child’s severed arm.

Behind me, Amy Jordan said, “Is there a frozen pizza or something?”

The arm had been cut off mid-biceps, and the raw tufted meat had frozen into a livid red scream against its gray skin.

“Or we could have sardines?” Amy opened another cabinet. “Jesus, what’s up with your dad and sardines?”

My family had ignored a secret stash of canned meat in the back of a kitchen cabinet for years, and then, when my dad moved out, for some reason he took every last, dusty one of them: Spam, clams in tomato sauce, anchovies, deviled ham. Sardines. They were the only actual food Amy and I had found when we started searching his beach house kitchen for breakfast. I mean, besides a black banana on the counter and half a jar of crunchy peanut butter he kept in the fridge.

Then I’d opened the freezer.

Amy and I always wound up together because she and her mom had moved in around the corner last year and we went to the same school. We weren’t best friends, but we were always giving each other rides, and that week we’d been out at Wallace Stoney’s graduation party at his parents’ beach house. We were juniors, but our school was grades one through twelve and the classes were small, so we’d all known one another forever. Wallace’s parents let him take over their beach house on Kiawah for a week, and seventy of us had been out there for days smoking Southern Magic (which was supposed to get you high but never did) and funneling Coors Light in the dunes. At night everyone who wasn’t hooking up in the beds passed out on the floors, and it all started over again in the morning.

I’d slept under a beach towel in a deck chair out back and woke up with the sun. I’d gone into the kitchen and found Amy opening and closing empty Domino’s boxes. We were tired and sandy and had headaches, so we decided to take off in my van before anyone woke up.

When my dad moved out he’d lived in a couple of clinically depressed apartments before realizing he was paying taxes on a perfectly good beach house out on Seabrook Island, so he packed up his clothes and his sardines and moved in. Seabrook was right next door to Kiawah, and it was 8:00 a.m. on a Saturday morning, which meant my dad would already be at the hospital, so I told Amy we could stop there to shower and get breakfast. It was too early for anything to be open except gas stations, and it was a long drive back into town.

“There’s Bisquick,” Amy said, opening the cabinet over the stove. “And a can of PAM.”

Excerpt continues below cover reveal.

My dad had wrapped the child’s arm in Saran wrap that was peeling loose, and now it lay over it like a sci-fi shroud. Its fingernails were blue and its fingers had curled into its palm. This frozen monkey paw rested on top of a Lean Cuisine (linguine with clam sauce).

“Why does your dad keep his peanut butter in the fridge?” Amy asked.

I don’t know. Why does he keep a child’s arm in the freezer?

Years later, Jim Jameson would get caught with a child’s severed foot in a crab trap. A tropical storm had come through Charleston and washed it up on Folly Beach, and the police started asking questions about, you know, a child’s severed foot in a crab trap, and Jim Jameson came forward and said it was his. He told them he was an orthopedic surgeon and the foot possessed an interesting bone deformity. After he’d amputated it, he’d asked the parents if he could keep it to use as a teaching tool. They’d said yes, and apparently the best way to get the meat off its bones was to let the crabs strip it.

When I read this in the paper I called Amy, because we’d gone to high school with Chrissy Jameson, Jim’s daughter.

“You know what they did after he said that?” Amy asked. “They gave it back to him.”

I never asked Chrissy about it because we didn’t really keep up. I’d had such a crush on her, though. She was soft-spoken and beautiful and super into art, and after we went to prom together everyone headed out to her grandmother’s place in Meggett. Her grandmother had been dead forever and no one had touched a thing in that house. Even the cans in the kitchen were from the seventies.

After a lot of Coors Light and a bit of Southern Magic, Chrissy asked me if I wanted to see something, and she took me into the big bedroom and I thought for sure we were going to hook up because we were standing right next to the bed, but instead she opened a drawer full of human hair. From back to front, from one side to the other, the drawer over-flowed with hair, shading from dark brown to light gray.

“It’s my grandmother’s,” Chrissy said. “From her brush. She saved it all her life. She thought throwing part of herself away was wrong.”

We didn’t hook up that night.

The following year, her mom divorced her dad and moved out to the Meggett house and turned it into an ostrich ranch. Five years after that, Jim Jameson was putting a child’s severed foot in a crab trap.

When I came home from New York that year I had Thanksgiving with my dad at his favorite restaurant, a hibachi place called Chow’s Steakhouse on Highway 17. While the chef turned a stack of onion slices into a volcano on the grill, I asked my dad about Jim Jameson’s foot.

“Isn’t it unethical or something?”

“Crabs are the best way to get the meat off the bone,” my dad said. “Everyone’s making a fuss over nothing.”

I pointed out that people ate crab out of the harbor, and there was now a greater than zero chance that the crab they were eating had eaten human flesh. My dad shrugged.

“You never ate a scab?”

Suddenly, I was overwhelmed with an urge to ask him about the arm. Because my dad wasn’t an orthopedic surgeon, he was a cardiologist, and there was nothing he could teach his students with a child’s severed arm. Just then, the chef catapulted a shrimp into the mouth of the little girl sitting beside us, and the whole table burst into applause.

“You know what’d happen if that got lodged in her trachea?” my dad asked.

I didn’t answer, because he was already pulling a ballpoint pen out of his shirt pocket.

“I’d lay her down on the floor and take this pen and jam it through her windpipe, right below her trachea. Then I’d pull out the ink cartridge and blow down it and give her mouth to mouth through the hollow body of this pen until the EMS arrived.”

My dad loved the idea of performing emergency surgery. When we were on an airplane and the captain asked if there were any doctors on board, my dad hit his call button like he was on Family Feud. When I was a kid we’d gone to the ballet, and halfway through the first act someone in the front row started hollering if there was a doctor in the house, and my dad practically hurtled the rows to get to them. Turned out they’d only fainted. No one could cheer him up after that, and we left at intermission. I could never figure out if his urge to perform emergency surgery was because he loved the rush or because he wanted us to see what he did for a living.

I saw what he did for a living. Once.

We’d taken my sister to college outside Boston and were walking back across the parking lot after dinner when we heard that sickening hollow boom of a car hitting another car. Even if you’ve never heard that sound before, you instantly know what it is. We all stopped and looked over at the dark stretch of road at the far end of the lot. It was on a blind corner, and as we watched, another car flew around it and slammed into the two wrecked cars. Then another. Then another. There was a pause, then from far away we saw a big pickup truck coming, way over the speed limit, and people on the street started shouting at the guy to stop, but he didn’t hear. He plowed into that five-car pileup at full speed. There was silence for a moment, then the people trapped in the cars started to scream. My dad ran like he was coming off the starting blocks at the four-hundred-yard dash, cardiologist division, leaving my mom and me behind. He came back to the hotel room after eleven that night, covered in blood. It was smeared up to his elbows, it was slathered across his knuckles and neck, it stained his pants. There was half a handprint on the chest of his shirt.

It was the first time I ever saw my dad covered in blood. It wouldn’t be the last.

_________