In the Sherlock Holmes canon, which totals fifty-six stories and four novels, Holmes is recorded as disguising himself eighteen times—wearing outfits and makeup as well as altering his voice—to change his age, nationality, class, and even gender.

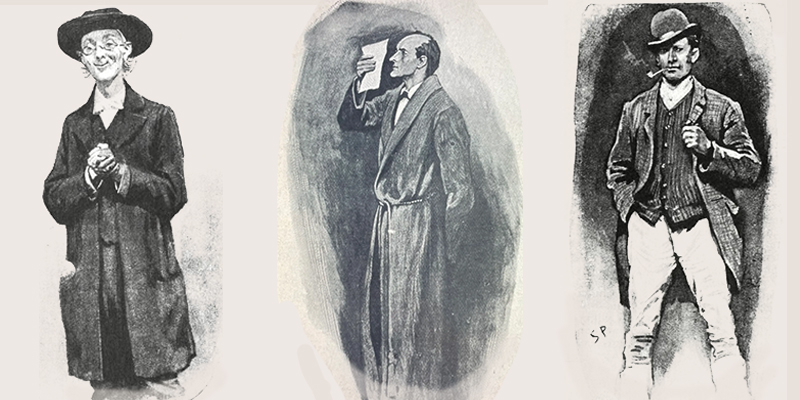

His known repertoire includes: an elderly book collector (“The Empty House”), a drunken groom (“A Scandal in Bohemia”), a young sailor (The Sign of the Four), an asthmatic elderly mariner (The Sign of the Four), an East End sea captain (“The Adventure of Black Peter”), an opium addict (“The Man with the Twisted Lip”), an accountant (“The Stockbroker’s Clerk”), a registration agent (“The Crooked Man”), a French blue-collar worker (“The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax”), an Irish-American spy (“His Last Bow”), an Italian priest (“The Final Problem”), a Norwegian explorer (“The Empty House”), an old sporting man (“The Mazarin Stone”), an unemployed workman (“The Mazarin Stone”), a flirtatious plumber (“Charles Augustus Milverton”), “a common loafer” (“The Beryl Coronet”), “an amiable and simple-minded Nonconformist clergyman” (“A Scandal in Bohemia”), and an old woman with a parasol (“The Mazarin Stone”).

As the adjectives in this roster suggest, Holmes does not merely use disguise to conceal his identity as a detective; he creates entirely new identities through numerous performative measures, designing characters to play for extended periods of time. Some of these characters are discarded after a day of surveillance; others are lived in for longer—Holmes proposes marriage to a woman while pretending to be the plumber in “Charles Augustus Milverton” and lives as the Irish American spy gathering intelligence for two years in the final Holmes story, “His Last Bow.”

Holmes is indeed a fine actor; in “A scandal in Bohemia,” Watson marvels at Holmes’s transformation into the clergyman, remarking that Holmes’s techniques “were such as Mr. John Hare” (a popular actor and the then-manager of London’s Garrick Theatre, who was known for playing pantaloons) “alone could have equaled,” adding: “It was not merely that Holmes changed his costume. His expression, his manner, his very soul seemed to vary with every fresh part that he assumed. The stage lost a fine actor, even as science lost an acute reasoner, when he became a specialist in crime.”

So, there you have it. Ta-da!