It Begins

I asked Iva and James to tell me everything they knew. They looked uncomfortable, whispering despite the fact that there wasn’t really anyone there but the barista.

The professor’s name was Karl Lamberg-Karlovsky, they said, and the story James had heard, like the one Morgan told me, was that this Harvard professor—tenured, and still on faculty—had an affair with his student and killed her when she wouldn’t end the liaison and threatened to tell either his wife or the university, he couldn’t remember which. His version also involved red ochre, but none of the cigarette butts. Red ochre, they explained, was used in many ancient burial rituals, either to preserve the dead or to honor them on their way to the afterlife. Its use seemed to limit the circle of suspects to someone with intimate knowledge of anthropology. Everyone in the department at Harvard, they said, knew the story. They had heard that another Harvard archaeology professor got too drunk at a recent faculty dinner and spilled the sordid tale to his students. In fact, they wouldn’t be surprised if most people in the field of archaeology knew and whispered about that particular professor.

I couldn’t understand how such a huge scandal, if any of it was true, could stay so quiet.

Iva and James explained that archaeology is a small and venal world. Everyone knows everyone’s business, but the rumors stay within the walls of the discipline. To figure out this murder, they implied, I would have to understand the world of academic archaeology.

———

From my dorm room that night, I Googled everything I could about the case, starting with “red ochre Harvard,” since I still hadn’t learned the victim’s name. While some of the more salacious aspects of Morgan’s original version turned out to be exaggerations, so much of it was there: the ochre, the Iranian dig, and reports of “hostilities” on the expedition. There was even mention of a cigarette butt that figured prominently in the crime scene. Gone was the jewelry on her neck and the ritual burns, but what my research turned up was stranger still. Jane’s father was the vice president of administration at Radcliffe College at the time of her death. If anyone had the power and clout to investigate, he did. But, it seemed, he never pursued it; in the articles, there was just a single mention of a grand jury hearing, and nothing about its outcome. Her death quietly faded into rumor. The lack of answers didn’t make sense.

And there was Professor Lamberg-Karlovsky—the one still on faculty— at the Cambridge Police precinct house on the day her body was found. “I came here to be of whatever assistance I can be to police,” he had told the Boston Globe. “I knew Jane both as an undergraduate student and a graduate student. She was an extraordinarily capable and talented girl [ . . . ] This doesn’t seem possible, her dying. I saw her just three days ago.”

And there he was again, in the New York Times: Professor Lamberg-Karlovsky pacing in the office of Stephen Williams, the director of the Peabody Museum and the head of the Anthropology department. “Both men have been stung by the impact of the sensational national publicity that has engulfed them,” Robert Reinhold, the Times’s Boston correspondent, wrote. The articles described Jane as brilliant, talented, attractive, good at many languages, great at drawing, a lover of Bach, and an accomplished horseback rider. She had grown up in Needham, Massachusetts, a quiet suburb on the outskirts of Boston, and her childhood, as one article put it, was “as American as Plymouth Rock.” She was a Girl Scout, a regular worshipper at Christ Episcopal Church, and she had excelled at Dana Hall, the prestigious all-girls boarding school in Wellesley she attended before Radcliffe. She loved Kurt Vonnegut and often quoted him. “Peculiar travel suggestions are like dancing lessons from God,” she would say, perhaps dreaming of digs in distant countries, though her favorite was from The Sirens of Titan: “I was a victim of a series of accidents, as are we all.”

A darkness crept around her edges as well. Jane had a reputation for her devastating wit, and if she wasn’t careful, her remarks pushed past clever to downright mean. According to Ingrid Kirsch, a friend from Radcliffe, Jane “had a kind of insight into people that was disconcerting. She could stop a conversation by coming out with a single sentence.” One of Jane’s favorite sayings was, “If justice be cruel and dishonesty be kind, then I prefer to be cruel.”

Despite this unflinching frankness, Jane was also portrayed as a “vulnerable person.” A former college friend questioned Jane’s friendliness to “hangers-on and acid heads who you would not call young wholesome Harvard and Radcliffe types.” There was talk of a secret abortion, and affairs with at least one professor.

If anything, Jane’s defining characteristic seemed to be her ability to evade straightforward description. As her neighbor Don Mitchell told the Times reporter: “It is not possible to characterize her lifestyle because she changed it so often. She was never taken in by any ethos, but she went through a period of painting on her wall and then she would not do that, then it was music and she would not do that.”

I recognized that mix of verve and self-doubt. That drive, that zest, and that vulnerability. I understood––or at least believed that I did––that at the center of this brilliant, vivacious woman was a loneliness and a fundamental need to find somewhere to belong that I knew all too well. I felt connected to her with a certainty more alchemical than rational.

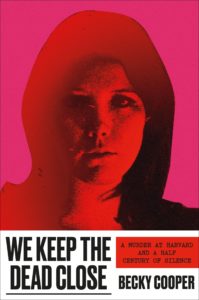

I wanted to see her face.

None of the online versions of the articles came with any picture, so I kept searching—combinations of her name, the professor’s name, the dig they went on, the name of her hometown—until finally, in one of the Iranian expedition monographs, I hit upon a black-and-white image from the 1968 season. It was a photograph of the eight-person crew that summer—plus Karl’s wife, the government’s antiquities representative, the cook, and a few local villagers—set against the background of the expedition Land Rover and the mountains. It read like a primer to the suspects in an Agatha Christie novel. Karl leaned against the Land Rover tall and handsome, while his wife, Martha, in a prim shift dress, positioned herself close enough that her arms brushed against his. Jim Humphries, Jane’s boyfriend, stood by himself in the back row, arms crossed, a head above everyone else, while four students whose names I did not yet know—Arthur and Andrea Bankoff, Phil Kohl, and Peter Dane— scattered themselves around the vehicle. Finally, lying on the ground at everyone’s feet, in a tight-fitting long-sleeved shirt with slacks and sneakers, her head propped on one elbow, her dark hair cascading down her arm, a cigarette in her other hand, was Jane. Her downward gaze was coy and irreverent, and her body zigzagged around the crew. She was six months shy of her end.

(ed. note—Karl Lamberg-Karlovsky was later cleared as a suspect into the investigation of Jane Britton’s murder.)

Secrets

That night, after reading all the articles I could find about Jane, I lay there unable to sleep. Some of what I was feeling was exhilaration. A lot of it was fear. The story, after all, appeared to have been effectively silenced; it seemed possible that Harvard had systems in place to ensure that it maintained control of the narrative. Would they kick me out of the school? Would I be disappeared by morning? Would someone come into my dorm and bash my head in? My conjectures were decreasingly tethered to reality. Still, I couldn’t be sure the lengths to which Harvard might go to make sure this story stayed buried.

But most of what was keeping me up was an incredulity verging on anger. Seeing Karl’s name in the articles had made the rumors about him feel plausible. If the story was true, why was no one listening or investigating? I couldn’t accept the possibility that this was just an open secret I would file away and move on from. The way I saw it, either Harvard had covered up a murder and was allowing a killer to remain on faculty, or we were imprisoning an innocent man with our stories. I wondered if I could be the one to take this rumor seriously.

The impulse to solve Jane’s case was a familiar one. As a child, I was obsessed with crime, with secrets, and with puzzles. One of my earliest memories is of being fixated on some graffiti underneath a piece of kindergarten playground equipment that said: jesse james was here. I became convinced that Jesse James was a fugitive who had left a network of clues on all the playgrounds in Queens. Every time I went to a playground, I always checked underneath the slides and under the dirty wooden slats. A wad of gum would turn into a signal to his bandit girlfriend that he had been there and was on the run, but still okay. Graffiti in the same pen but a different handwriting meant that someone was close on his tail.

In middle school, my drive to investigate fed my affinity for being an observer, and I became a watcher, a chameleon of social habits. I tried to conceal the fact that I almost always felt like an outsider by scrutinizing the way people talked, the way people ate, and then adopting the patterns of those around me.

Later, I dreamed of becoming a forensic analyst, a cryptographer, a neuroscientist with a focus on abnormal psychology—anything that let me be the one to solve mysteries. I ultimately chose writing because I felt I could, through narrative, get into the mind of my character in a way that was more real, if less scalably objective, than by scrutinizing calcium and potassium channels.

Over the years, I never lost my sense that there was more under the surface or my desire to get inside the dark. But lying there that night, I was also old enough to recognize that my belief that I could solve a murder on my own that had eluded cops for over forty years might be as naive as the thought that I could find the whereabouts of Jesse James.

———